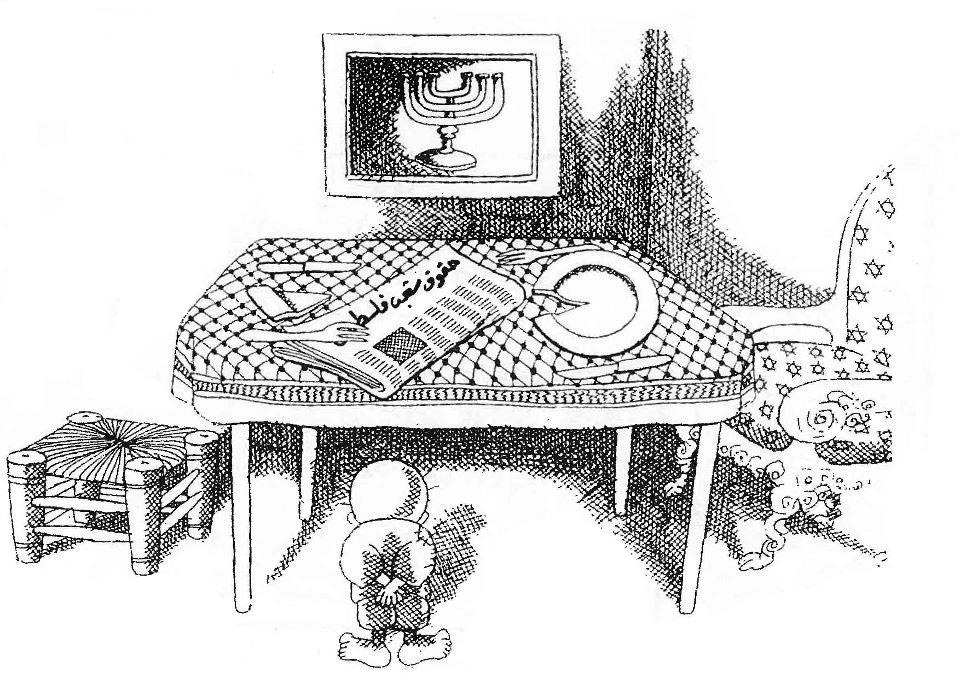

Newspaper: The Rights of the Palestinian People

“The only way to stop this evil [loss of land], is for all the red men to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land as it was at first, and should be now — for it never was divided, but belongs to all for the use of each.” —Chief Tecumseh. Esarey, Logan, ed. Messages and Letters of William Henry Harrison, Vol. 1. Indiana Historical Commission, 1922, pp. 463-466.

“The white men are not friends to the Indians: at first, they only asked for land sufficient for a wigwam; now, nothing will satisfy them but the whole of our hunting grounds, from the rising to the setting sun.” —Chief Tecumseh. Hunter, John Dunn. Manners and Customs of Several Indian Tribes Located West of the Mississippi. J. Maxwell, 1823, p. 68.

“First kill me before you take possession of my Fatherland.” —Chief Sitting Bull. Vestal, Stanley. Sitting Bull: Champion of the Sioux. Houghton Mifflin, 1932, p. 194.

“You come here to tell us lies, but we don’t want to hear them. If we told you more, you would have paid no attention. That is all I have to say.” —Chief Sitting Bull. Utley, Robert M. The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull. Henry Holt and Co., 1993, p. 267.

“If I agree to dispose of any part of our land to the white people I would feel guilty of taking food away from our children’s mouths, and I do not wish to be that mean.” —Chief Sitting Bull. Vestal, Stanley. Sitting Bull: Champion of the Sioux. Houghton Mifflin, 1932, p. 140.

“The country was made without lines of demarcation, and it is no man’s business to divide it… Do not misunderstand me, but understand me fully with reference to my affection for the land. I never said the land was mine to do with it as I chose. The one who has the right to dispose of it is the one who created it. I claim a right to live on my land and accord you the privilege to live on yours.” —Chief Joseph. Direct excerpt from his famous speech “An Indian’s View of Indian Affairs,” delivered in Washington D.C. in 1879. Published verbatim in the North American Review, Volume 128, Issue 269, in April 1879 (p. 412-433).

“I have not hesitated to tell this House, again and again, that we could not always hope to maintain peace with the Indians; that the savage was still a savage, and that until he ceased to be savage, we were always in danger of a collision, in danger of war, in danger of an outbreak.” —Scottish settler colonial John Alexander Macdonald. House of Commons Debates, Official Report, 1st Session, 5th Parliament, Volume 2 (4 May 1885), p. 1582.

“When the European settlers arrived, they needed land to live on. The First Nations peoples agreed to move to different areas to make room for the new settlements.” — Complete Canadian Curriculum (Grade 3), Popular Book Company (Canada) Ltd., 2017.

Canada’s performative recognition of the state of Palestine is the ultimate hypocrisy—a gesture dripping with the unacknowledged guilt of a settler-colonial state. This act is not a break from history but its continuation: a modern diplomatic maneuver built upon a foundation of racist and imperial logic laid by its founding architects. To understand the profound cynicism of this recognition, one must return to the words of “Supreme Court Justice” Ivan C. Rand, a key figure in the 1947 Partition of Palestine, who articulated the core belief that has animated Canadian colonial policy for decades: that Palestine was to be an outpost for “the ethical values and civilizing influence of the West.”

This Canadian view, as Rand proudly stated, was a direct mimicry of Theodor Herzl’s 1896 declaration that a Jewish state would serve as a “rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.” Rand’s statement is not a historical relic; it is the key to deciphering Canada’s consistent role. It reveals a worldview that divides humanity into the civilized and the barbaric, the West and the Orient—a binary used to justify the ongoing settler-colonial project on Turtle Island and the Nakba in Palestine. This is the same civilizing mission used to justify the theft of Indigenous lands through the Indian Act, the violent dispossession of territories, and the residential school system designed to “kill the Indian in the child.” It is the same logic that framed the Nakba not as a catastrophic expulsion of a native people but as the noble establishment of a Western “anchorage.”

Canada’s dirty past is inextricably linked to its role in Palestine. As detailed in analyses of Canada’s early position, its support for Partition was never neutral or pragmatic; it was an ideological commitment to a settler-colonial project it intimately understood. Lester B. Pearson and Rand saw in zionism a kindred spirit: a European-derived movement that would create a friendly “outpost” to buffer against Soviet influence and, more deeply, against the native Arab society they viewed with Orientalist disdain. The indigenous inhabitants of Palestine were, in this calculus, rendered invisible—obstacles to progress, their history and rights blotted out to make way for the march of Western civilization, just as the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island were deemed obstacles to Confederation, colonial expansion, and the formation of an imaginary Canadian national character.

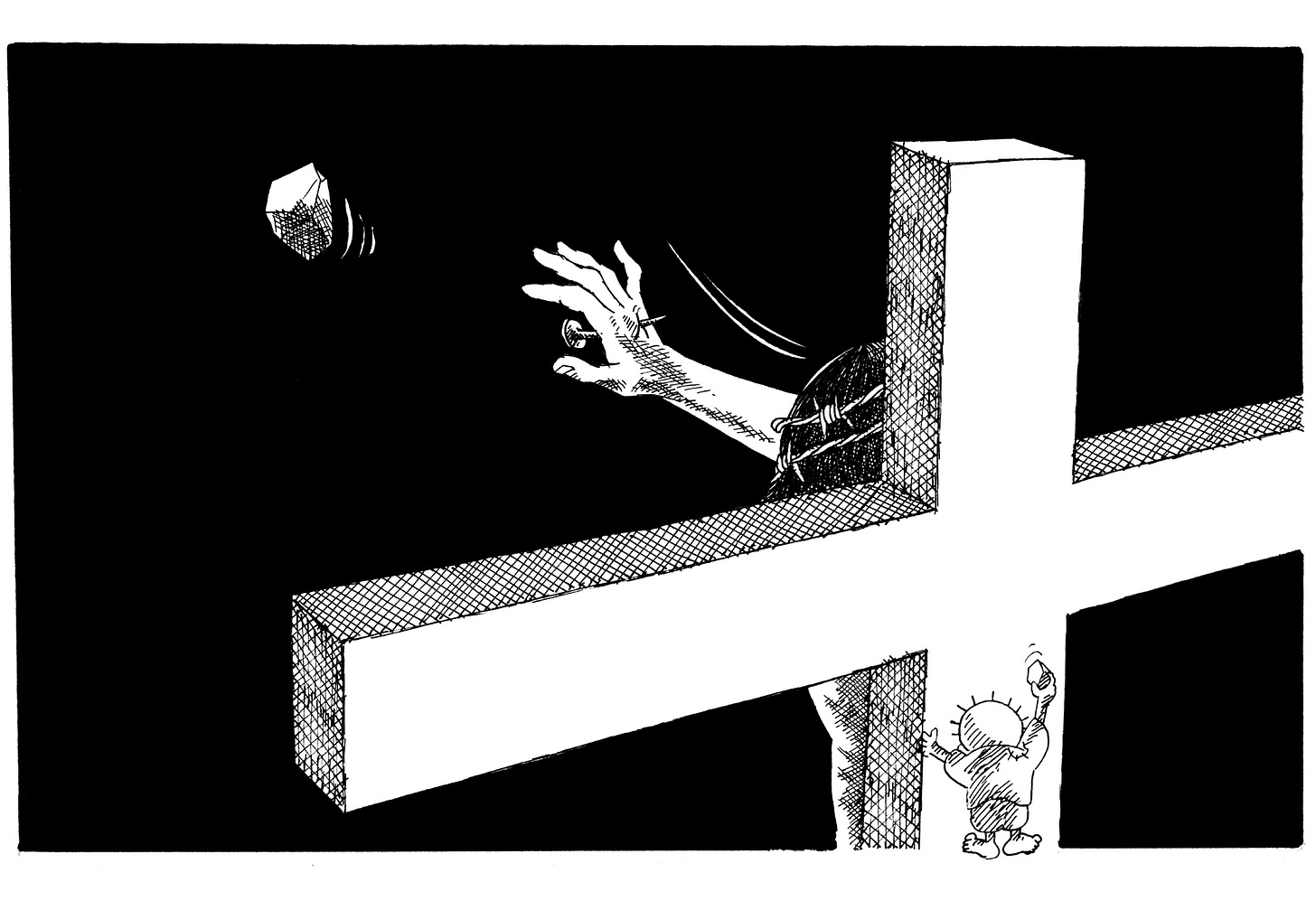

This foundational erasure, practiced domestically and exported abroad, dictated Canada’s subsequent approach to the Palestinian right of return. How could a people deemed uncivilized savages have a right to return to a land now occupied by a civilizing outpost? The Canadian government’s solution was to recast the refugees as a humanitarian problem, a burden to be managed and resettled elsewhere. In internal memos, officials like Jules Léger argued that Arabs must accept that “Israel has come to stay” and that refugees must be resettled in Arab lands, echoing the settler-colonial policy of forced assimilation and displacement of First Nations in Canada. The small 1955 Canadian refugee admission program was not about justice but about setting a precedent for permanent ethnic cleansing, neutralizing the “threat to regional security” posed by the rightful owners of the land living too close to their stolen homes.

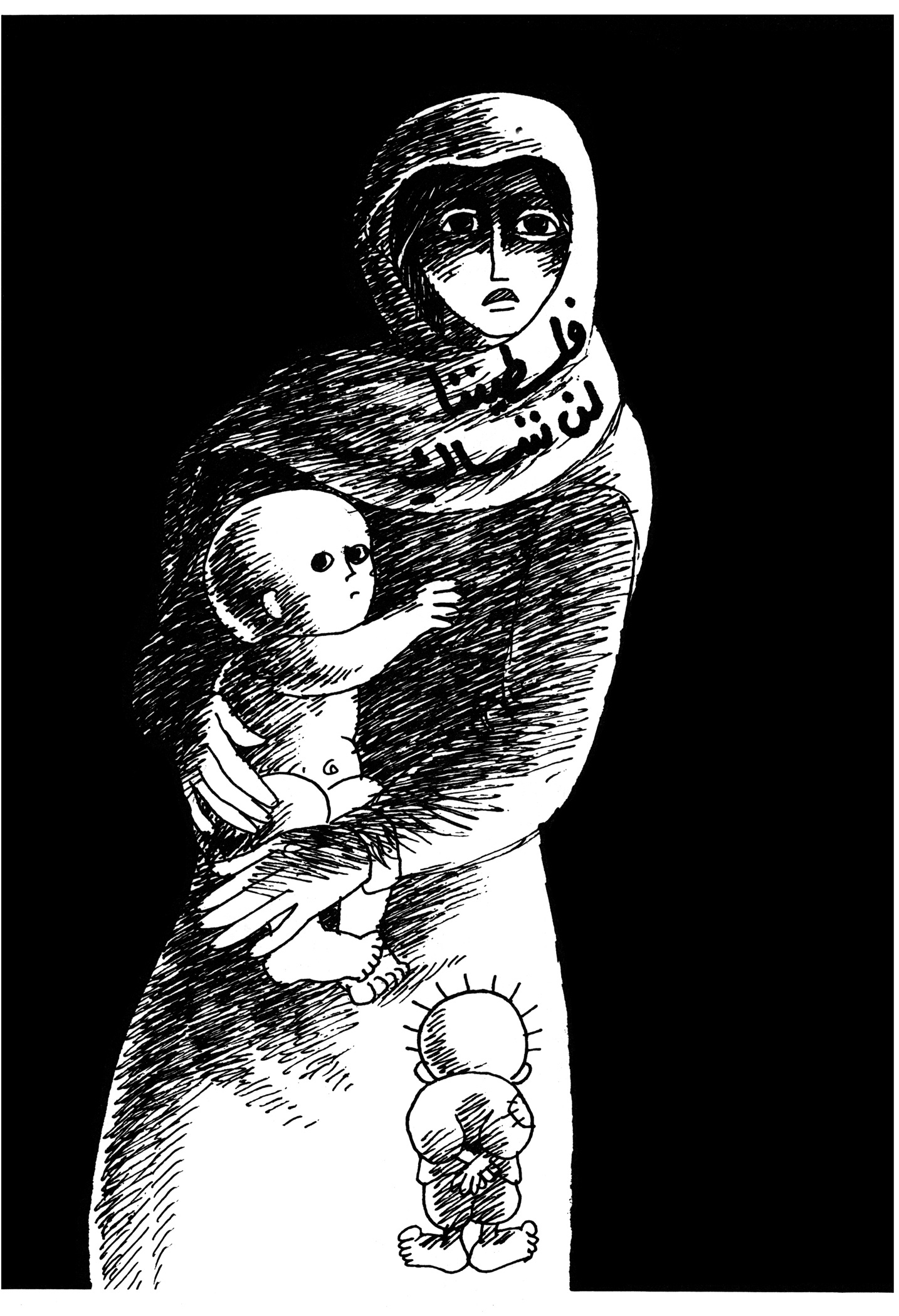

Our Palestine, We Will Never Forget You.

This philosophy of resettlement over return became Canada’s steadfast policy, perfectly aligning with Israeli interests. While paying lip service to UN Resolution 194, Canadian leaders across party lines—from Pearson’s call for “token repatriation” to Diefenbaker’s unwavering support (a man who, as a member of the pre-statehood Canadian Palestine Committee, was dedicated to establishing a Jewish majority state)—pushed for the dissolution of the Palestinian people into the Arab diaspora. They blamed the victims, with MPs accusing Arab states of “indoctrinating the refugees with hatred,” a rhetoric that mirrors the colonial trope of the “ungrateful native” refusing the gift of civilization—a trope long used against Indigenous communities in Canada resisting their own erasure.

This same Randian logic infected Canada’s role in the Oslo-era “negotiations.” Chaired by Canada precisely because of its pro-Israel bias, the Refugee Working Group became a mechanism to suppress the right of return, dismissed by a Canadian gavel-holder as a “myth.” Canada’s mission was to reduce an inalienable political right to a technical discussion about “compensation regimes” and “living conditions”—to manage the natives rather than grant them justice. This is the modern face of the “civilizing” mission: using the language of humanitarian aid and process to bury a right and uphold a settler-colonial status quo, just as the Canadian settler state has used bureaucratic processes and empty reconciliation rhetoric to avoid addressing Indigenous land rights and sovereignty at home.

Nowhere is this hypocrisy more grotesque than in Canada’s calculated refusal to name the ongoing genocide in Palestine. A state built upon the completed genocide of Indigenous nations—a fact it still will not fully admit, let alone atone for—now positions itself as a sober arbiter of international law, parsing words while children are dismembered and starved by a regime it helped create and arm. This is the ultimate shame: a guilty state of genocide, having finished its bloody work on Turtle Island, now provides diplomatic cover for a new genocide, one whose ideological foundations it helped pour. The bitter irony is cosmic: Canada, a state that has never reconciled with its own mass graves, dispatches its “peacekeeping forces” abroad to sanctimoniously stabilize the world’s “peace”—a peace built upon the very genocidal logic it perfected at home. This is not peacekeeping; it is the maintenance of a violent, colonial order, ensuring the continued silence of the victims and the impunity of the killers, whether in Gaza or Grassy Narrows.

The hypocrisy is further exposed by Canada’s active silencing of dissent and suppression of any narrative that challenges its settler-colonial ally, mirroring the Canadian state’s historical and ongoing suppression of Indigenous resistance and scholarship that exposes its own foundational crimes.

Today, Canada’s recognition of a Palestinian statelet on the fragments of the 22% of Palestine it helped to dismember is the culmination of this century-long project. It is an attempt to impose a final settlement that permanently extinguishes the right of return, confining the native population to disconnected bantustans while blessing the Israeli occupation state and its apartheid zionist regime that controls everything from the river to the sea and beyond. It is the “civilizing outpost” graciously granting limited autonomy to the natives it has permanently displaced.

Before guilty Canada can utter a single word about Palestine, it must first confront the racist, settler-colonial legacy of its Ivan Rands and its own dirty past as a settler colony on Turtle Island. It must remember its own apartheid, its Indian Act, the lies of treaties—some of which were blank pages—and make meaningful reparations for genocide and land theft. It must repudiate the poisonous idea that its values are a universal gift to be imposed upon others. True solidarity requires not recognition on the terms of the oppressor but an unwavering commitment to dismantling the architecture of apartheid everywhere—from the Jordan River to the Ottawa River—and upholding the right of all Palestinians to return to their homes and the right of all Indigenous peoples to their lands and sovereignty.

Until then, the words of the Canadian state are as empty as the promises made to Chief Sitting Bull, and its “peace” is as violent as the dispossession described by Chief Tecumseh. This recognition is not a step toward justice but the ultimate act of Canadian settler-colonial hypocrisy.