And the land, hitherto a common possession like the light of the sun and the breezes, the careful surveyor now marked out with long-drawn boundary lines. Not only were corn and needful foods demanded of the rich soil, but men bored into the bowels of the earth, and the wealth she had hidden and covered with Stygian darkness was dug up, an incentive to evil. And now noxious iron and gold more noxious still were produced: and these produced war – for wars are fought with both – and rattling weapons were hurled by bloodstained hands.

(Ovid, written around 8 AD which laments humanity’s loss of its original Golden condition [Ovid Metamorphoses, Book 1, The Iron Age]). ((From Memories and Visions of Paradise: Exploring the Universal Myth of a Lost Golden Age by Richard Heinberg (1989).))

The privatisation of property, extractivism, the necessity for food-producing slaves and a warrior class to sustain and further extend the aims of the elites are all neatly summed up in this quote from Ovid. What is noticeable and notable is that over the millennia very little has changed in substance. We still have today wage slaves, standing armies, extractivism and industrialised agriculture that is oriented and controlled according to the aims and agendas of a warmongering elite. However, it seems that things were not always thus.

The coming of the Kurgan peoples across Europe from c. 4000 to 1000 BC is believed to have been a tumultuous and disastrous time for the peoples of Old Europe. The Old European culture is believed to have centred around a nature-based ideology that was gradually replaced by an anti-nature, patriarchal, warrior society. According to the archeologist and anthropologist, Marija Gimbutas:

Agricultural peoples’ beliefs concerning sterility and fertility, the fragility of life and the constant threat of destruction, and the periodic need to renew the generative processes of nature are among the most enduring. They live on in the present, as do very archaic aspects of the prehistoric Goddess, in spite of the continuous process of erosion in the historic era. Passed on by the grandmothers and mothers of the European family, the ancient beliefs survived the superimposition of the Indo-European and finally the Christian myths. The Goddess-centred religion existed for a very long time, much longer than the Indo-European and the Christian (which represent a relatively short period of human history), leaving behind an indelible imprint on the Western psyche. ((The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization, by Marija Gimbutas/Joseph Campbell (2001), p. xvii.))

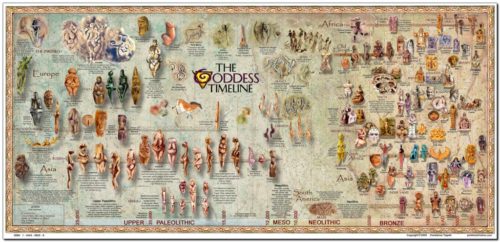

?The Goddess Timeline

?The Goddess Timeline

A chronological record of archaeological images of women and goddesses on a uniform time scale from 30,000 BCE to the present.

Copyright © 2012 Constance Tippett

Gimbutas notes that it was at this time that a relatively homogeneous pre-Indo-European Neolithic culture in southeastern Europe was “invaded and destroyed by horse-riding pastoral nomads from the Pontic-Caspian steppe (the “Kurgan culture”) who brought with them violence, patriarchy, and Indo-European languages”. While this model has been disputed over the years recent research has broadened and deepened our understanding of these movements.

In 2015 an international team of researchers conducted a genetic study which backs the Kurgan hypothesis, that “a massive migration of herders from the Yamna culture of the North Pontic steppe (Russia, Ukraine and Moldavia) towards Europe which would have favoured the expansion of at least a few of these Indo-European languages throughout the continent.”

Another disputed aspect of the hypothesis is the ‘how’- whether “the indigenous cultures were peacefully amalgamated or violently displaced.” However, the representations of weapons engraved in stone, stelae, or rocks appear after the Kurgan invasions as well as “the earliest known visual images of Indo-European warrior gods”. ((The Chalice and the Blade, Riane Eisler (1998) p 49.)) The beginning of slavery is also seen to be linked to these armed invasions.

According to Riane Eisler, archeological evidence “indicate that in some Kurgan camps the bulk of the female population was not Kurgan, but rather of the Neolithic Old European population. What this suggests is that the Kurgans massacred most of the local men and children but spared some of the women who they took for themselves as concubines, wives, or slaves.” ((The Chalice and the Blade, Riane Eisler (1998) p 49.)) Gimbutas believed that the pre-Kurgan society of Old Europe was a “gylanic [sexes were equal], peaceful, sedentary culture with highly developed agriculture and with great archtectural, sculptural, and ceramic traditions” which was then replaced by patriarchy; patrilineality; small scale agriculture and animal husbandry”, the domestication of the horse and the importance of armaments (bow and arrow, spear and dagger). ((The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization, by Marija Gimbutas/Joseph Campbell (2001), p. xx.))

Not so th’ Golden Age, who fed on fruit,

Nor durst with bloody meals their mouths pollute.

Then birds in airy space might safely move,

And tim’rous hares on heaths securely rove:

Nor needed fish the guileful hooks to fear,

For all was peaceful; and that peace sincere.

Whoever was the wretch, (and curs’d be he

That envy’d first our food’s simplicity!)

Th’ essay of bloody feasts on brutes began,

And after forg’d the sword to murder man.— Ovid Metamorphoses Book 14

The idea of a fall, the end of a Golden Age is a common theme in many ancient cultures around the world. Richard Heinberg, in Memories and Visions of Paradise, examines various myths from around the world and finds common themes such as sacred trees, rivers and mountains, wise peoples who were moral and unselfish, and in harmony with nature and described heavenly and earthly paradises.

In another book, The Fall: The Insanity of the Ego in Human History and the Dawning of a New Era, Steve Taylor takes a psychological approach to the concept of the Fall examining what he calls the new human psyche and the Ego Explosion (which created a lack of empathy between human beings) and resulted in our alienation from nature while making us both self and globally destructive.

However, James DeMeo takes a more radical approach in his book, Saharasia: The 4000 BCE Origins of Child Abuse, Sex-Repression, Warfare and Social Violence in the Deserts of the Old World. He believes that climatic changes caused drought, desertification and famine in North Africa, the Near East, and Central Asia (collectively Saharasia) and this trauma caused the development of patriarchal, authoritarian and violent characteristics.

God creates Man

God creates Man

“Then the LORD God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.”(Gen 2:7)

Author unknown, Creation of Adam, Byzantine mosaic in Monreale, 12th century.

The arrival of violent, enslaving tribes and of a supreme male deity led to the eventual demise of the female deities through demotion or destruction of temples and statues. ((See: When God Was a Woman, Merlin Stone (1978) pp. 66-67.)) Over time, the many traditions of pre-patriarchal nature worship were destroyed (such as cutting down sacred trees) or eventually assimilated into the new patriarchal religions (see my Christmas article). Thus many of the nature-based ideas of matriarchal religion were turned on their head as the male deity creates man and Adam gives birth to Eve. According to Barbara Walker, in The Women’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets, “usurpation of the feminine power of birth-giving seems to have been the distinguishing mark of the earliest gods.” She lists the many ways the male deities ‘gave birth’; e.g., from the mouth (Prajapati), from the head or thigh (Zeus), from the penis (Atum), or from the stomach (Kun) in the section ‘Birth-Giving, Male’.

Adam ‘gives birth’ to Eve

Adam ‘gives birth’ to Eve

“For man did not come from woman, but woman from man”(1 Corinthians 11:8)

From: Master Bertram, Grabow Altarpiece, 1379-1383

In Christianity the rulers had a religion that assured their objectives. The warring adventurism of the new rulers needed soldiers for their campaigns and slaves to produce their food and mine their metals for their armaments and wealth. Thus, Christ was portrayed as Martyr and Master. In his own crucifixion as Martyr he provided a brave example to the soldiers and as Master he would reward or punish the slaves according to how well they had behaved.

Christ as Martyr and Master

Christ as Martyr and Master

Jan van Eyck (before c. 1390 – 9 July 1441)

Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych, c. 1430–1440.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Christianity, according to Helen Ellerbe:

has distanced humanity from nature. As people came to perceive God as a singular supremacy detached from the physical world, they lost their reverence for nature. In Christian eyes, the physical world became the realm of the devil. A society that had once celebrated nature through seasonal festivals began to commemorate biblical events bearing no connection to the earth. Holidays lost much of their celebratory spirit and took on a tone of penance and sorrow. Time, once thought to be cyclical like the seasons, was now perceived to be linear. In their rejection of the cyclical nature of life, orthodox Christians came to focus more upon death than upon life. ((The Dark Side of Christian History, Helen Ellerbe (1995) p. 139.))

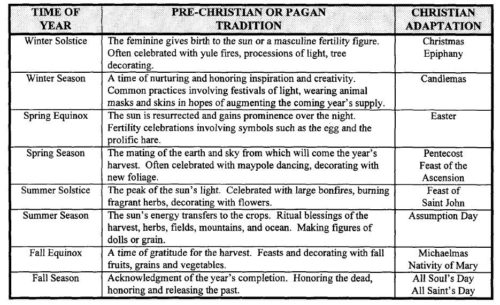

?Pagan festivals chart: [From The Dark Side of Christian History, Helen Ellerbe]

?Pagan festivals chart: [From The Dark Side of Christian History, Helen Ellerbe]

Christian eschatology (study concerned with the ultimate destiny of the individual soul and the entire created order) and the idea of linear time took over from the people’s strong connection with nature and the ever-changing seasons. Although, in early medieval times, according to David Ewing Duncan in The Calendar, the peasants still lived and died “in a continuous cycle of days and years that to them had no discernible past or future.” ((The Calendar: The 5000-year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens – and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days, David Ewing Duncan (2011) p. 137.)) Different seasonal festivals such as the solstice, the Nativity, Saturnalia, Yuletide, the Easter hare and Easter eggs etc. all had pre-Christian connections but old habits died hard and left the church no choice but to incorporate some aspects of them into their own traditions over time.

Feminism vs class

While some aspects of the culture of prehistory are still with us today, interpretation of the artifacts from archeological digs has always been open to controversy. For example, Cynthia Eller in her book The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why An Invented Past Will Not Give Women a

Future believes that the theory of a prehistoric matriarchy (female rulership) was “developed in 19th century scholarship and was taken up by 1970s second-wave feminism following Marija Gimbutas.” However, the feminist historian Max Dashu notes that Eller “makes no distinction between scholarly studies in a wide range of fields and expressions of the burgeoning Goddess movement, including novels, guided tours, market-driven enterprises. All are conflated all into one monolithic ‘myth’ devoid of any historical foundation.”

The important point here is that ideas of matriarchal prehistory have been used in feminist theory to blame men for war and violence today (ignoring Thatcher and May). Sure, men have been dominant in the warring elites but many, many more men were caught up in the enslaved soldiers, miners and farmers classes. And as it was violence that was used to enslave them in the first place historically, then surely it would be no surprise if violence is used by them in the fight back against their slavery (class struggle).

The reappraisal of our ancient past and our relationship with nature has become an urgent necessity as climate chaos occupies more and more of our time and energy. It is not too late to learn from the myths of the Golden Age and Ovid’s ancient complaints to create a better future.

This let me further add, that Nature knows

No steadfast station, but, or ebbs, or flows:

Ever in motion; she destroys her old,

And casts new figures in another mould.— Ovid, Metamorphoses Book 15