Wounds have opened; recriminations are all around. The Rio Olympic Games, even before the first act, has already shown how it will be one of the more interesting ones for all the wrong reasons. (Eventually, such wrong reasons tend to seem right.)

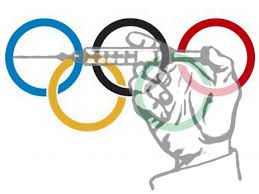

A glaring feature of the latest ruckus lies in the administration (or maladministration) of international sport. Disagreement, for instance, about regulating doping regimes and taking action about them, is particularly fractious. Multiple deals, often of a trans-national nature, have been made over the years. The cover-up is very much in.

No notable international organisation has been sparred bungling on the issue, or succumbing to the temptations associated with the crooked path. Football’s world governing body FIFA remains mired in the rot, in search of the redemptive powers of reform. (The current head, Gianni Infantino, was implicated in the Panama Papers scandal, which revealed co-signed offshore deals with an indicted official made by Europe’s football governing body, UEFA.)

The athletics governing body IAAF has not proven itself an angel of cleanliness, having been put through the WADA wringer as well. Earlier this year, the IAAF former president Lamine Diack was found to have “sanctioned and appeared to have had personal knowledge of the fraud and extortion of athletes carried out by the actions of the illegitimate governance structure he put in place.” This suggests an enduring tension between on-track or field events, which have a dynamic of their own, and the pen pushing, buck passing antics behind the scenes.

The athletics governing body IAAF has not proven itself an angel of cleanliness, having been put through the WADA wringer as well. Earlier this year, the IAAF former president Lamine Diack was found to have “sanctioned and appeared to have had personal knowledge of the fraud and extortion of athletes carried out by the actions of the illegitimate governance structure he put in place.” This suggests an enduring tension between on-track or field events, which have a dynamic of their own, and the pen pushing, buck passing antics behind the scenes.

Volleys have been traded by the International Olympic Federation and World Anti-Doping Agency, the former claiming they have been left with a mess, the latter that the IOC should have shown more backbone. The ever present issue here is Russia.

The IOC is certainly cutting it fine on the event, having claimed on Sunday night that a final ruling on the expulsion of Russia’s athletes may well be delayed until hours prior to this Friday’s opening ceremony. Assistance to that end would be provided by a three-member panel of executive board members.

IOC President Thomas Bach suggested that it was “very obvious” that the “timing” of the WADA-commissioned report investigating state-doping allegations on the part of Russia, was poor. Nor was the IOC responsible for accreditation, or supervision of laboratories tasked with detecting cases of doping.

“The IOC cannot be made responsible neither for the timing nor for the reasons of these incidents we have to face now and which we are addressing and have to address just a couple of days before the Olympic Days.”

The IOC, most notably Bach, has also received a good deal of opprobrium from European papers and various officials in the business, arguing that he has an unhealthy proximity to Moscow. The Daily Mail speculated about how Bach had “enjoyed a coffee” with the Russian President, assuming sharing such fluids would somehow qualify as evidence why he might be soft on the Russians.

The German paper Bild went in determined fashion for the jugular, calling Bach “Putin’s poodle” while the Daily Mail went for a toothless theme, a coward incapable of throwing his weight around. Matt Lawton indignantly suggested on July 25 that the IOC had “destroyed the Olympics” by its qualified decision.

Not barring the entire Russian team was deemed by such critics a logical necessity, indispensable for cleaning the sport. Much of it, in fact, smacked of colossal slothfulness, the classic behaviour of those incapable of exercising the judgment of natural justice. It also provided another conclusion: having found its bogeyman, international sports could go forth blissfully aware that drug taking was still taking place. Eventually, things would settle down.

Invariably, the discussion sounds of giddying high morality and principle. Within the Olympic camp itself, the Australian Olympic chef de mission Kitty Chiller has also taken it upon herself to wage what can only be a crusade against everything connected with Russia. Her mood has not been helped by a fire that started in the basement of the Australian building that forced team members to evacuate the premises, the theft of Zika-protective shirts during that evacuation, and the loss of a laptop.

On Russia, a cranky Chiller had little time for the legal niceties of prizing the drug cheat from the untainted athlete. A degree of deep, near fire and brimstone puritanism has characterised her approach to the sporting event. On Thursday, she insisted that Moscow’s efforts to organise a separate event featuring the banned athletes was nonsensical, sending “the wrong message.”

Chiller’s comments have to also be considered as part of a more specific, self-interested exercise. Australian teams have been on stand-by waiting for a blanket ban on Russia. Exit Russia, and then, in some cases, enter those teams that would not have otherwise qualified. The women’s eight rowing crew has already gotten lucky on that score.

Bach’s point, for all the problems typical of the IOC pigsty, is that caution must be exercised. It was not according the athlete any degree of solid justice to “punish an individual for the failures or manipulations of your government”. Whether that exercise is done credibly before the opening ceremony is quite another matter. The waters have already well and truly been poisoned.