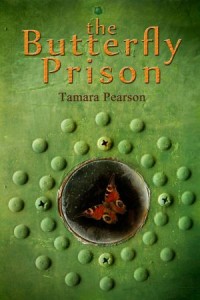

The Butterfly Prison begins slowly, combining seemingly disconnected stories that are taking place in poor neighborhoods of Australia. The stories are like tiny vignettes; shy, modest, minimalistic but always significant and beautifully told. A fear here, a bitter humiliation there, a dream of a child interrupted by a police officer.

Then suddenly, the stories begin to interconnect, intertwine, and the novel gains speed. Real pain – deep and overwhelming – emerges. Profound hurts, bitterness and injuries are slapping the faces of the characters, and somehow, we are drawn in and begin suffering with them.

It is Australia that we don’t know; that we are not supposed to see. After some 40 pages I thought, “it feels little bit like Carpentaria”, but then, just a few pages later, it did not feel like anything else, it only felt and read like the The Butterfly Prison.

Then they dreamed the same dream. The whole world had been stolen, and people tumbled about on it like hungry and lost refugees in a foreign land. All spaces seemed to be owned by private companies. And the world had fences in strange places. And many long walls.

Paz couldn’t move, and his real leg jerked as though he had fallen down stairs. Mella murmured. In the stolen world they walked carefully, trying not to upset anything, like visitors. Because it wasn’t their home. Barbed wire between their toes. They bumped into another wall and got a new bruise, and it seemed that there were bluebruised people everywhere discovering new walls.

A queue then to buy back a bit of the world: a little bit of space for $2.5 million, so they could have somewhere to sit down. But they had no money, so they walked and walked and bumped into walls.

“A stolen world”! That could easily be the second title of the novel.

*****

Tamara Pearsen is my friend, and my comrade; she is a true revolutionary.

She is a person who spent several years fighting for the Latin American revolutions, for “the process”, first in Venezuela and then in Ecuador. She gave everything to the revolution, never looked for privileges, and never demanded special treatment. She is pure and she is really strong. She saw it all, from the bottom, from the angle of real people.

When she told me that she wrote a novel, I was almost certain that it would be about South America, based in Venezuela, Ecuador or Bolivia.

When she told me that she wrote a novel, I was almost certain that it would be about South America, based in Venezuela, Ecuador or Bolivia.

But Tamara decided to write about Australia, about her complex homeland.

We sat in a Vietnamese restaurant in Quito, Ecuador, when she said, simply:

“After all these years, it is time to go back; to visit Australia… I am scared.”

But she already went back. The Butterfly Prison is her great return home. Instead of explaining Latin American revolutions to Australian people, she depicted an Australian reality through the eyes of a Latin American revolutionary.

An oppressed and humiliated woman, a child living in hopelessness, adults with no future, a chocking and merciless consumerism, a country that already reached its zenith but without managing to bring zeal, enthusiasm and happiness to its people: those are some of many images of Australia that will stay in our sub-consciousness after reading the The Butterfly Prison.

Australia – the land where native people were robbed of everything and where they are, until now, living in appalling destitute. Australia, which belongs to the elites; Australia where one has to comply with the ruling-class narrative, or to be crushed and humiliated.

Tamara told me why she wrote the novel:

The Butterfly Prison is life and soul wrenched out and turned into a tale, as a way of saying some things that need to be said – of screaming them in fact. It is unravelling dominant ideas so that beauty, for example, can be what it really is, and we can get some hope from that. Its my grain of sand of solidarity with so many others who have been made invisible in different ways, and I hope that it can reach some of those people and connect with them in that magical way that stories do, and even inspire them.

In this, she definitely succeeded.

The Butterfly Prison is filled with compassion and solidarity. It is also full of beauty: not that cheap sentimental beauty of the popular literature of the 21st Century, but of profound, lasting beauty found only in life itself, and in the great works of art.

Two lives of Tamara Pearsen have merged in one powerful novel: one of her childhood and sadness of her native land, Australia, and the other, that of her epic battle for a better world which she has been fighting for many years in Latin America.

As the novel progresses, it becomes fully international, with many stages built into its pages: those in India, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Argentina… The battles rage… But at closer look, there is really only one battle: that for our humanity, for human dignity, and for human kindness.

Life, as temporary as a kiss on a cheek: already gone, but a little tingle that lingered behind. Mella thought of the things people of her generation had grown up to believe would last forever: countries, poverty, and capitalism. Yet all those things were gone now. Nothing was forever, nothing was so powerful, except for change.

Now a Latin American writer, or more precisely “an internationalist” writer, a socialist realist, a revolutionary, Tamara Pearsen, returned home, on the wings of imagination, through her powerful novel The Butterfly Prison, uniting several realities into one. She demands change and she does it determinedly but affectionately. And the result is stunning.