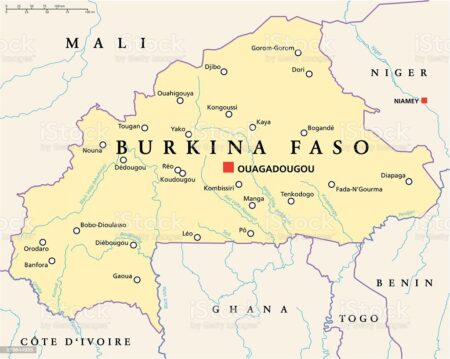

On January 24th, Burkina Faso bore witness to its third destabilizing coup in less than a decade. It also marked the eighth successful putsch American soldiers launched in multiple West African countries since 2008. The Intercept reports that Ouagadougou’s new leader, Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, took part in many United States led AFRICOM (Africa Command) exercises and an American sponsored military intelligence course. This disturbing pattern raises serious questions about what the U.S. army is teaching its African allies.

The U.S. developed an alarming habit for training individuals likely to commit horrendous crimes after the outbreak of the Cuban Revolution in 1959. The School of the Americas (renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation in 2001) based in Fort Benning, Georgia spent decades teaching the dark arts of torture and counterinsurgency warfare to thousands of Central and Latin American soldiers and aspiring dictators keen to annihilate socialist or peasant movements. Distinguished alumni include Bolivian autocrat Hugo Banzer, Panamanian strongman turned drug lord Manuel Noriega, and El Salvadoran Colonel Domingo Monterrosa. Monterrosa led battalions that slaughtered a thousand civilians in the village of El Mozote, according to anthropologist Lesley Gill.

Guatemalan SOA students enjoyed exceptional careers as well. Proud graduates like dictators Efraín Rios Montt, General Fernando Lucas García, and various members of Guatemala’s feared D-2 intelligence agency terrorised the indigenous and impoverished Mayan community into submission over a nearly four decade-long civil war. Devastating scorched earth campaigns, which reached their apogee in the early eighties, wiped out hundreds of Mayan villages and almost all their inhabitants. Journalist Zach El Parece noted that a member of the infamous “Kaibiles” Special Forces, a unit that bludgeoned children to death with hammers for being communist sympathisers in the village of Dos Erres, among many others, later became an instructor at the SOA.

The Guatemalan Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH) concluded that the Guatemalan army was responsible for displacing 1.5 million people and murdering or vanishing most of the war’s 200,000 victims. The CEH deemed the army’s atrocities so severe that they amounted to acts of genocide against the Mayan population. The report even singled out the United States’ crucial role in reinforcing Guatemala’s homicidal “national intelligence apparatus and for training the officer corps in counterinsurgency techniques, key factors which had significant bearing on human rights violations…”

The U.S. government also paid millions to train Indonesian soldiers implicated in Jakarta’s barbaric occupation of East Timor. Amnesty International revealed that approximately 7,300 Indonesian officers took part in IMET (International Military Education and Training) courses at U.S.-based army, navy, and air-force schools between 1950 and the early nineties. Washington promised to cancel military aid to Indonesia after the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre, during which Indonesian troops killed 271 protesters at a peaceful pro-independence rally in the Timorese capital of Dili. However, they secretly continued to train elite Kopassus troops. This regiment, according to the Guardian, indulged in “some of the worst human rights violations in Indonesia’s history”.

Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia’s current Minister of Defence, trained at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, finished first in his class, and re-joined the Kopassus after returning home. Historian Gerry van Klinken and journalist Jill Jolliffe believe it is highly likely that Subianto participated in the brutal suppression of the East Timorese uprising of 1983-84. A former Indonesian intelligence employee alleged that Subianto directed anti-insurgent operations that butchered hundreds of innocent civilians. Soldiers executed surrendering women and children on sight, while countless others endured starvation, torture, sexual abuse, and arbitrary detention in overcrowded concentration camps. Moreover, reporter David Jenkins claims the Kopassus eagerly adopted tactics the shadowy U.S. Phoenix program perfected during the Vietnam War—a program that assassinated thousands of Vietnamese peasants with impunity. The abhorrent methods of U.S. trained “Contra” death squads in Nicaragua proved quite influential among the Kopassus as well.

Scholar Noam Chomsky asserts that Jakarta’s invasion of East Timor incurred “perhaps the greatest death toll relative to the population since the Holocaust…” Approximately 200,000 East Timorese perished in the Indonesian onslaught, while survivors still suffer the long-term effects of napalm and chemical weapon poisoning. The Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation in East Timor issued a damning verdict: the U.S. backed Indonesian military deliberately imposed unbearable conditions of life which almost exterminated the East Timorese. A genocide in paradise, to borrow Matthew Jardine’s haunting phrase.

U.S. Special Forces also trained the Tutsi RPA (Rwandan Patriotic Army) in the late nineties as it decimated refugee camps and massacred Hutu exiles fleeing into the jungles of eastern Congo. Many of them were sickly and starving civilians that had nothing to do with the Tutsi genocide of 1994. Le Monde and The Irish Times cited French intelligence findings and Pentagon papers stating that U.S. instructors and mercenaries provided combat training to dozens of Rwandan officers. Some reports even alleged that U.S. advisers accompanied the RPA as it expanded its rampage into the Congo. These destructive incursions marked the opening salvo in the DRC’s (Democratic Republic of the Congo) endless “world war”—a cataclysmic conflict that has caused, thus far, the deaths of millions.

Historians and authors like Filip Reyntjens, René Lemarchand, and Judi Rever largely agree that the RPA, along with the Ugandan and Burundian-backed AFDL (Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire) rebel group, killed tens of thousands of Rwandan and Congolese Hutus in the DRC between 1996-97. A United Nations report released in 2010 insisted that in most cases perpetrators did not carry out these atrocities unintentionally in the heat of battle and may be guilty of “crimes of genocide”.

Yet the U.S. is not alone in enabling, unwittingly or otherwise, regimes prone to committing egregious crimes. In December 2008, Guinean Army Captain Moussa Dadis Camara spearheaded the “German Coup” which brought a military junta into power in Conakry. Deutsche Welle reported that Camara and his co-conspirators received extensive training from the German Armed Forces in Bremen. German-trained paratroopers unleashed a wave of extreme violence against peaceful protestors in Conakry Stadium less than a year after Camara suspended the Guinean constitution and threadbare republican institutions.

Amnesty International said that security forces murdered more than 150 people, wounded hundreds more, and raped or assaulted dozens of women and girls with sticks, bayonets, rifle butts, and batons in broad daylight. A failed assassination attempt quickly disposed Camara, only for another ruthless soldier—the Moroccan, French, and Chinese trained Sékouba “The Tiger” Konaté—to take his place. To this day, undiscerning European Union member states continue to provide military training and weapons to African countries hampered by weak civilian governments and very powerful armies. It is a recipe for disaster.

Ideally, massive grassroots movements in both the U.S. and West Africa should try to convince representatives to bring a permanent end to these borderline colonial military exchanges. Following that, Congress must enact more legislation that would strengthen background checks for future trainees. Furthermore, any manuals, textbooks, or instructors advocating torture and other unlawful or inhumane tactics need to be removed and replaced with courses that seek to improve civic-military relations.

However, adding human-rights awareness or international law modules to military curricula is by no means an effective solution. Political scientist Jacob Ricks worries that promoting courses or practices geared towards professionalizing and enhancing the social responsibilities of the military is a lackluster strategy. Survey data demonstrates that many high-ranking Siamese soldiers, already among the largest recipients of US IMET programs now replete with professionalizing courses, are statistically more likely to support a coup or greater military interference in Siamese politics and society. Thailand has weathered 19 coup attempts since 1932. Teaching soldiers to respect the sanctity of human life, democracy, and the rule of law, although necessary and beneficial, is clearly not enough to curb such vicious tendencies.

West African politicians and civil society groups need to be more creative and ambitious if they ever hope to tame their often unruly armies. Professor Kwesi Aning, head of academic affairs and research at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Ghana, told University World News that African states keep sending troops abroad for training because they do not possess the resources or facilities required to properly train them at home. This breeds a dangerous imbalance of power as foreign-trained troops, imbued with delusions of superiority and entitlement after studying in the U.S., France, or Germany, could return home with a burning desire to take control. Depending on the lessons, especially in the U.S., foreign-trained soldiers might begin to perceive fellow citizens not as ordinary people who need protection but as potential or internal enemies to be eradicated.

Constructing homegrown, truly sovereign, and well-funded military academies, devoted to teaching civic-military cooperation and unencumbered by harmful relations with exploitative armies in the Global North, would be a step in the right direction. To paraphrase Colonel Jahara Matisek, West African nations must develop military institutions steeped in their own histories and cultures. Only then can trustworthy armies emerge and the coup curse finally fade.