On March 10, 2003, I gave a very well-attended lecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology — yeah, a high school grad speaking to post-doctoral students and faculty at M-I-friggin-T. (I also gave a talk at Yale later that year but that’s for another article.) Please allow me to introduce some context.

I once had a reasonably large global audience for my writing and commentary. My articles covered a lot of ground. I didn’t like to be pigeonholed so I wrote about virtually everything — and still do.

One of my most popular articles back then was published in 2002, around the one-year anniversary of 9/11. Themed “the other 9/11,” it broke down the details of the September 11, 1973, U.S.-sponsored coup in Chile. In particular, the article focused on the role of the notorious Henry Kissinger (one of the architects of the current Great Reset, btw).

Let’s review some of the details of my original article and the “other” 9/11, shall we?

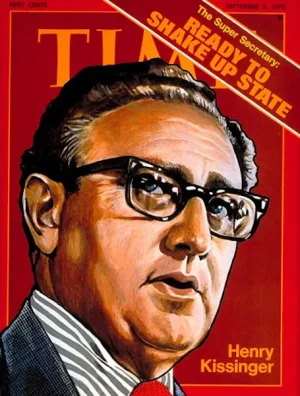

Time Magazine: September 3, 1973

Time Magazine: September 3, 1973

Ten days after the Salvador Allende government was overthrown in a September 11, 1973, coup in Chile, U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Jack Kubisch told the House Subcommittee on Inter-American Affairs: “Gentlemen, I wish to state as flatly and as categorically as I possibly can that we did not have advance knowledge of the coup.”

Information made available in roughly 5,000 documents declassified in 1999 told a vastly different — yet sadly predictable (for those paying even an iota of attention) — story.

For those of you still wondering “what’s really going on” in places like Syria, Iraq, Ukraine, etc., it might help to study some history.

Time Magazine: September 24, 1973

Time Magazine: September 24, 1973

Salvador Allende, a physician by trade and nominally a social democrat reformer, first gained worldwide attention when he came within 3 percent of winning Chile’s 1958 presidential election. Six years later, the United States decided to not leave such elections to chance. It was time to introduce the Chilean people to Democracy™, American-style.

The U.S. government, mostly through the covert efforts of the Central Intelligence Agency, spent more money per capita to support Allende’s opponent, Eduardo Frei, than Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater combined spent that same year in the American presidential election.

With an estimated $20 million of U.S. taxpayer money to work with, the CIA embarked on a program of anti-communist propaganda and disinformation designed to scare Chilean citizens — specifically mothers — into believing that an Allende victory would result in direct Soviet control of their country and their lives.

“No religious activity would be possible,” they were told. Their children, hammer, and sickle stamped on their foreheads would be shipped to the USSR to be used as slaves, the radio and newspapers direly warned.

The scare tactics worked.

While Allende won the male vote by a small margin, 469,000 more Chilean women chose Frei. Cleverly manipulated to fear the “blood and pain” of “godless, atheist communism,” the mothers of Chile voted against the man who promised to “redistribute income and reshape the economy” through the nationalization of some major industries (like copper mining) and the expansion of agrarian reform.

A far cry from Leninism, Allende’s policy of “Eurocommunism” (communists linking with social democratic parties into a united front) was for the most part, as unacceptable to the Kremlin as it was to the White House. But who needs reality when there are nation-states to own?

When the 1970 Chilean presidential election rolled around, Salvador Allende was still a major player and, despite another wave of U.S.-funded propaganda, he was elected president of South America’s longest functioning democracy on September 4, 1970.

However, he had a new and powerful enemy: Dr. Henry Kissinger.

The 40 Committee was formed with Kissinger as chair. The goal was not only to save Chile from its irresponsible populace but to yet again stave off the Red Tide™.

“Chile is a fairly big place, with a lot of natural resources,” explains Noam Chomsky, “but the United States wasn’t going to collapse if Chile became independent. Why were we so concerned about it? According to Kissinger, Chile was a ‘virus’ that would ‘infect’ the region.”

At a September 15, 1970, meeting called to halt the spread of infection, Kissinger and President Nixon told CIA Director Richard Helms it would be necessary to “make the [Chilean] economy scream.” While allocating at least $10 million to assist in sabotaging Allende’s presidency, an outright assassination was also considered a serious and welcome option.

The respect held by the Chilean military for the democratic process led Kissinger to pick as his first assassination target, not Allende himself, but General Rene Schneider, head of the Chilean Armed Forces. Schneider, it seems, had long believed that politics and the military should remain discrete. Despite warnings from Helms that a coup might not be possible in such a stable democracy, Kissinger urged the plan to proceed.

When the killing of Schneider only served to solidify Allende’s support, a CIA-sponsored media blitz similar to that of 1964 commenced. Citizens were faced with daily “reports” of Marxist atrocities and Soviet bases supposedly being built in Chile. U.S. threats to cut economic and military aid were also used to help cultivate a “coup climate” among those in the military. These two approaches represented the hard and soft lines outlined by Nixon and Kissinger.

How soft was soft? Edward Korry, U.S. ambassador to Chile at the time, articulated the soft sell by declaring that the U.S. task was “to do all within our power to condemn Chile and the Chileans to utmost deprivation and poverty.” Korry warned, “not a nut or bolt [will] be allowed to reach Chile under Allende.”

On the hard side, Dr. Henry began securing support for a possible military coup.

“In 1970,” wrote historian Howard Zinn, “an ITT director, John McCone, who had also been head of the CIA, told Kissinger and Helms that ITT was willing to give $1 million to help the U.S. government in its plans to overthrow the Allende government.”

“The stage was set for a clash of two experiments,” says author William Blum. Allende’s socialism was pitted against what was later called a “prototype or laboratory experiment to test the techniques of heavy financial investment in an effort to discredit and bring down a government.”

This clash would reach its climax on September 11, 1973. The socialist experiment ended in violence on the other 9/11 and Allende himself was said to have committed suicide… with a machine gun.

Of course, the U.S. claimed no complicity in or even knowledge of the coup at the time. However, as mentioned above, the State Department’s declassified documents told a far different story.

For example, a CIA document from the day before the coup stated bluntly, “The coup attempt will begin Sept. 11.” Ten days later, the Agency announced, “severe repression is planned.” With thousands of opponents of the new regime gathered in soccer stadiums, a September 28 State Department document detailed a request from Chile’s new defense minister for Washington to send an expert advisor on detention centers.

Allende was dead. In his place, the people of Chile now faced brutal repression and human rights violations, book burnings, powerful secret police, and more than 3,000 executions. Tens of thousands more were tortured and/or disappeared. Shortly after the coup, U.S. economic and military aid once again began to flow into Chile.

The man in charge of all this was General Augusto Pinochet, a man Dr. Kissinger could really get behind. “In the United States, as you know, we are sympathetic to what you are trying to do,” Kissinger told the Chilean dictator in 1975. “We wish your government well.

“My evaluation,” he continued to Pinochet, “is that you are the victim of all the left-wing groups around the world and that your greatest sin was that you overthrew a government that was going communist.”

Later that same year, when facing a roomful of Chilean diplomats concerned about the effect Pinochet’s human rights violations might have on world opinion, Henry was in top form: “Well, I read the briefing paper for this meeting and it was nothing but human rights. The State Department is made up of people who have a vocation for the ministry. Because there were not enough churches for them, they went into the Department of State.”

Was Kissinger really that concerned with the minor nationalization of industry proposed by Salvador Allende or were other forces at work here?

Here’s how the CIA saw it three days after Allende won the election: “The U.S. has no vital national interests within Chile. The world military balance of power would not be significantly altered by an Allende government. [But] an Allende victory would represent a definite psychological advantage for the Marxist idea.”

“Even Kissinger, mad as he is, didn’t believe that Chilean armies were going to descend on Rome,” says Chomsky. “It wasn’t going to be that kind of an influence. He was worried that successful economic development, where the economy produces benefits for the general population — not just profits for private corporations — would have a contagious effect. In those comments, Kissinger revealed the basic story of U.S. foreign policy for decades.”

Accordingly, in 1974, when the new U.S. ambassador to Chile, David Popper, complained about Chile’s human rights violations, Dr. Kissinger promptly sent these orders: “Tell Popper to cut out the political science lectures.”

Fortunately, the political science department of MIT did not adhere to Kissinger’s edict.

The “viral” (2002-style) nature of my Chile piece prompted them to reach out, asking me to visit the school and give a talk. They paid my way on Amtrak and put me (and my partner at the time) up for two nights in a local motel.

When we arrived at the lecture hall, I opened the door to peek in. It was jam-packed. My partner gasped but I didn’t flinch. Alexander Cockburn once wrote, “The first duty of an intellectual is to know what’s going on and that’s a lot of work.” I live and breathe that line and even used it in my talk when I joked about how MIT degrees don’t make you an intellectual. [Cue the nervous laughter]

Yep, I was ready and my performance proved it. The audience of faculty members and graduate students and post-doctoral types sat rapt for about an hour as this high school grad connected all the dots. They got their chance in the post-talk Q&A and grabbed it with both hands. The discussion started out, of course, being about Chile and/or Kissinger. Soon though, I was hit with rapid-fire queries on an astonishingly broad range of topics.

Truth be told, I knocked all their questions out of the park until they gave up and applauded. Audience members rushed up to talk with me and even take photos with me. It was a goal attained, a dream come true.

When we got back to the motel room, however, we discovered that the toilet was seriously clogged. It was late and no maintenance worker could be found. So the front desk dude lent me a plunger. Still dressed in my fancy, talk-giving outfit, this “intellectual” unclogged the motel toilet for the next 15 or 20 minutes.

Today — almost 20 years after my MIT talk — I chuckle as I remember how I spent most of March 10, 2003, with a literal or metaphorical plunger in my hands.

My life in 2022: same shit, different toilet.