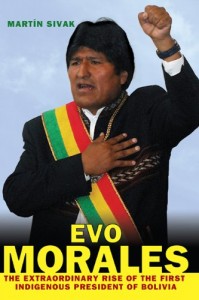

Although the rhetoric against the left-leaning governments in Latin America in the US media has calmed down since the Obama administration moved into the White House, it is safe to assume that the continuing popularity of these governments and their alliances with those Washington considers enemies concerns the foreign policy establishment. As Argentine journalist Martin Sivak’s biography of Bolivian president Evo Morales makes clear, that concern is justified. This book, titled Evo Morales: The Extraordinary Rise of the First Indigenous President of Bolivia, makes it clear that this new generation of leaders is intent on altering the historical relationship between Washington and its neighbors to the South.

Sivak, who is a friend of Morales, describes Morales’ rise from a campesino family to the first indigenous leader of Bolivia. Brief anecdotes are related about Morales’ youth that include beginning work at the age of seven, joining the Bolivian military as a teen and eventually involving himself in efforts to organize campesinos, coca growers and Bolivian workers in their struggle against the traditional power elites in the nation of Bolivia.

The reader is taken inside the planes carrying Morales from village to city in his native land as he meets with friends and occasional foes. They are also transported along with Sivak, Morales and his closest aides to Cuba, Europe and other parts of the world as Morales meets with other national leaders. Relationships with those leaders are discussed, especially the relationships Morales has with Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez. These journeys provide a catalyst for Sivak discuss Morales’ policies and the history behind those policies. It is a history that incorporates Morales’ personal political journey, the history of those Bolivians who support him, and the history of Bolivia.

As mentioned before, the history of Bolivia is a history whose essential elements revolve around the relationship between the indigenous peoples of the land and the descendants of the Spanish invaders. It is a study in discrimination based on ethnic origin and class; traditional religion and Catholicism; and the people of Bolivia and its northern neighbor. Today, it is a struggle between the campesinos and workers and the neoliberal corporate order and those elements of the Bolivian elite that support them. Evo Morales and his supporters understand this most recent manifestation of Bolivian history as a threat to not only their way of life but to the national integrity of Bolivia. His opponents in the traditional elites, on the other hand, see Morales and his government as a threat to their way of life–a life that depends on the elites delivering the resources of Bolivia to foreign interests and keeping whatever profit for themselves and their power structure.

As mentioned before, the history of Bolivia is a history whose essential elements revolve around the relationship between the indigenous peoples of the land and the descendants of the Spanish invaders. It is a study in discrimination based on ethnic origin and class; traditional religion and Catholicism; and the people of Bolivia and its northern neighbor. Today, it is a struggle between the campesinos and workers and the neoliberal corporate order and those elements of the Bolivian elite that support them. Evo Morales and his supporters understand this most recent manifestation of Bolivian history as a threat to not only their way of life but to the national integrity of Bolivia. His opponents in the traditional elites, on the other hand, see Morales and his government as a threat to their way of life–a life that depends on the elites delivering the resources of Bolivia to foreign interests and keeping whatever profit for themselves and their power structure.

The current manifestation of this historical conflict is the subject of the last couple sections of Sivak’s book. Most striking in the story he relates is that Morales, unlike some of his Latin American compatriots, refuses to compromise with those who would sell his nation to Washington and other points northward. Confident in his support and mostly untainted by the power he wields, Morales has proven over and over that he will not sell out his supporters nor his agenda. As a resident of the United States, I only wish we had political leaders with the conscience of Evo Morales. Hell, I wish we had political leaders with a conscience.

Martin Sivak has written a personal tale of a political man. In doing so, he has told the story of the man, the movement he helped build, the struggles of a people for justice and dignity and the struggles of a nation for economic and political independence.

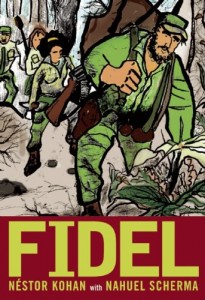

Given that one of Morales’ mentors and allies is none other than Fidel Castro, this seems an appropriate place for a brief mention of a recently published biography of Castro. The book, titled Fidel: An Illustrated Biography of Fidel Castro is translated from the Spanish. Written by Nestor Kohan, this illustrated text presents a version of Fidel rarely seen in the United States. After a few pages discussing his youth and student years, Kohan presents the biography of a heroic individual dedicated to the people of Cuba and the struggle against imperialism. More than a comic book version of Fidel, but less than a full-fledged biography, this pocket-sized text is a friendly introduction to the Cuban revolution and the man synonymous with its continuing story.

Given that one of Morales’ mentors and allies is none other than Fidel Castro, this seems an appropriate place for a brief mention of a recently published biography of Castro. The book, titled Fidel: An Illustrated Biography of Fidel Castro is translated from the Spanish. Written by Nestor Kohan, this illustrated text presents a version of Fidel rarely seen in the United States. After a few pages discussing his youth and student years, Kohan presents the biography of a heroic individual dedicated to the people of Cuba and the struggle against imperialism. More than a comic book version of Fidel, but less than a full-fledged biography, this pocket-sized text is a friendly introduction to the Cuban revolution and the man synonymous with its continuing story.