The Fed’s $12.8 trillion of monetary stimulus has triggered a six-week long surge in the stock market. Think of it as Bernanke’s Bear Market Rally, a torrent of capital gushing from every rusty pipe in the financial system. The Fed’s so-called “lending facilities” have gone far beyond their original purpose, which was to backstop a broken system. Now they’re leaking liquidity into the equities markets and sending stocks soaring while the “real” economy sinks to the bottom of the fish tank. That’s how the Fed does business these days: plenty of tasty crepes for the Wall Street kingpins and table scraps for the lumpen masses.

Bernanke has provided generous “100 cents on the dollar” loans for Triple A mortgage-backed collateral that is now worth 30 cents on the dollar. The Fed stands to lose trillions of dollars on these loans because the assets will never regain their original value. Eventually the taxpayer will have to pony up the difference in higher taxes, fewer public services and a weaker dollar.

Bernanke’s liquidity injections may have sparked a flurry of speculation, but they won’t end the recession or slow the downward spiral. The relentless system-wide contraction continues apace and all of the leading economic indicators point to a deepening slump that will last for two years or more. Here’s a clip from a recent statement from the IMF:

Recessions associated with financial crises have typically been severe and protracted. Financial crises typically follow periods of rapid expansion in lending and strong increases in asset prices. Recoveries from these recessions are often held back by weak private demand and credit reflecting, in part, households’ attempts to increase saving rates to restore balance sheets. They are typically led by improvements in net trade, following exchange rate depreciations and falls in unit costs.

Globally synchronized recessions are longer and deeper than others. Excluding the present, there have been three episodes since 1960 during which 10 or more of the 21 advanced economies in the sample were in recession at the same time: 1975, 1980 and 1992 . . . Recoveries are usually sluggish, owing to weak external demand.

The recession will be a long uphill slog regardless of developments in the stock market. Bernanke admitted as much last Thursday when he said that the collapse of U.S. lending will cause “long-lasting” damage to home prices, household wealth and borrowers’ credit scores:

“One would be forgiven for concluding that the assumed benefits of financial innovation are not all they were cracked up to be. . . . The damage from this turn in the credit cycle — in terms of lost wealth, lost homes, and blemished credit histories — is likely to be long-lasting.”

Unlike Treasury Secretary Geithner, Bernanke has been surprisingly candid in his analysis of the crisis. That doesn’t mean that his policies have been worker-friendly. Far from it. But he has been a lot more honest about the shortcomings of deregulation and financial innovation. So far, the meltdown has wiped out more than $11 trillion of household wealth, sent unemployment skyrocketing, and pushed millions of people from their homes. As Bernanke admits, the country will not quickly bounce back.

Economists Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart have conducted a study on the last 18 international financial crises and compiled their findings in a document called “Is the 2007 U.S. Subprime Financial Crisis So Different?” What they discovered was that “rising public debt is a near universal precursor of other post-war crises” and that countries that experienced large capital inflows were particularly vulnerable to crises. By 2006, two-thirds of the world’s surplus capital was flowing into the United States via its current account deficit. This flood of foreign capital kept interest rates low, housing and equity prices high, and Wall Street flush with money. Now foreign investment is drying up, housing prices are falling, the secondary market is frozen, and deflation is setting in across all sectors of the economy.

Rogoff and Reinhart believe that “recessions that follow in the wake of big financial crises tend to last far longer than normal downturns, and to cause considerably more damage. If the United States follows the norm of recent crises, as it has until now, output may take four years to return to its pre-crisis level. Unemployment will continue to rise for three more years, reaching 11–12 percent in 2011.” (Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart, “Don’t Buy the Chirpy Forecasts,” Newsweek)

The proliferation of opaque, unregulated debt-instruments (MBSs, CDOs, CDSs) also played a big role in the present crash by reducing transparency and increasing systemic instability. Here’s Rogoff and Reinhart:

Assuming the U.S. continues going down the tracks of past financial crises, perhaps the scariest prospect is the likely evolution of public debt, which tends to soar in the aftermath of a crisis. A base-line forecast, using the benchmark of recent past crises, suggests that U.S. national debt will rise by $8.5 trillion over the next three years. Debt rises for a variety of reasons, including bailout costs and fiscal stimulus. But the No. 1 factor is the collapse in tax revenues that inevitably accompanies a deep recession.

Tax revenues are already falling sharply across the country as the recession deepens. In fact, Bloomberg News reports that, “State and local sales-tax revenue fell more sharply in the fourth quarter of 2008 than at any time in the past half century . . . ” (Corporate and personal income taxes are also declining at a record pace.) That makes it impossible to predict the ultimate cost of the crisis. But what makes it even harder is that Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner refuses to remove toxic assets from the banks balance sheets using the usual “tried and true” methods. A recent report from a congressional oversight committee (The Warren Report) revealed that there are three ways to fix the banking system: liquidation, reorganization and subsidization. Geithner has rejected all three of these preferring to implement his own makeshift Public Private Investment Program (PPIP), which is thoroughly untested, has no base of public or political support, and is clearly designed to shift the toxic debts of the banks onto the taxpayer through publicly-funded non recourse loans. (Geithner’s plan will allow the banks to establish off-balance sheet operations so they can buy their own bad assets from themselves using 94 per cent public money) The whole thing is an obvious swindle papered over with gibberish.

So far, less than $10 billion has been transacted through Geithner’s PPIP, a mere drop in the bucket. The IMF estimates that the banks and other financial institutions may be holding up to $4 trillion in toxic assets. At the current rate, Geithner’s strategy will take a century to succeed. The Treasury Secretary knows his plan won’t fix the banking system; he’s just hoping that the economy rebounds before the government is forced to nationalize the big banks. It’s just a stalling ploy, but even so, there are risks. As the economy worsens, the likelihood of another financial meltdown or a run on the dollar increases. Foreign central banks and investors are getting restless and want to see the Treasury take positive steps to fix the system. In recent months, China has slowed its purchases of US Treasuries, traded tens of billions of USD in currency swaps, and has gone on a spending spree for raw materials — all to protect itself from weakness in the dollar. According to Bloomberg:

“People’s Bank of China Zhou Xiaochuan called for the establishment of a “super-sovereign reserve currency” last month after Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao said he’s worried a weaker US dollar may hurt China’s investments. Inflation and a depreciating dollar would erode the value of US holdings owned by international investors.”

Again, Bloomberg:

“China, Japan and Korea should establish a routine mechanism to diversify the region’s reserve currencies away from the dollar, the China Securities Journal reported, citing central bank adviser Fan Gang. The Asian countries need to consider setting up a transitional arrangement to help reduce reliance on the dollar before the problems in the international financial system are resolved.”

Geithner’s foot dragging could be extremely costly for America’s long-term economic prospects. The Treasury Secretary should be tackling the toxic assets problem head-on and stop the dilly-dallying; there’s no time to lose.

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “The world economy is in the midst of its deepest and most synchronized recession in our lifetimes, caused by a global financial crisis and deepened by a collapse in world trade.”

The vicious contraction has spread to every sector without exception — industrial output, credit, private consumption, exports, retail, residential investment, housing, equities prices and manufacturing — all have seen sharp cutbacks or plunging revenues. The spurious notion that “green shoots” are beginning to sprout up, is just more happy talk to divert attention from the severity of the impending storm.

The Fed is in way over its head and Bernanke knows it. Nothing is working — not the zero-percent interest rates, nor the multi-trillion dollar lending facilities, nor monetizing the debt by purchasing long-term Treasuries. It’s all been a flop. Financial institutions are deleveraging, businesses are slashing inventory, and corporations are laying off workers in droves. More than 40 percent of the credit that was sloshing around the economy via low interest loans has dried up. The banks aren’t lending and Wall Street’s credit-generating contraption — securitization — has broken down bursting the humongous equity bubble and precipitating a sudden decline in economic activity. There are no quick fixes. It will take years to reassemble the broken pieces or design a new financial architecture. It’s the end of an era.

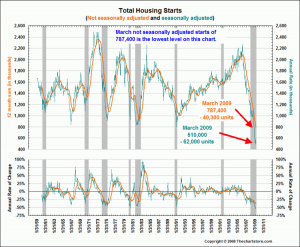

As for housing; the situation is devolving beyond anyone’s wildest expectations. It’s not a Depression, it’s bigger and more savage — an Uber-Depression! Take a look at this chart from Barry Ritholtz’s The Big Picture.

We are in uncharted water in a leaky boat.

Housing is a millstone that’s dragging down the whole economy. The Wall Street bulls can enjoy their “sucker’s rally” for now, but it’s going to be short-lived. The fundamentals have never been this bad. It’s like a chapter from Revelation. The banks are padding their earnings reports with accounting trickery to hide their losses. The consumer is underwater and worried about losing his job or getting evicted from his home. And the government is trying to conceal the damage to the financial system through trillion dollar stealth bailouts that never get congressional approval. It’s a real mess, and the problem is that there’s just too much debt. Martin Wolf of the Financial Times summed it up like this last Monday:

Consider the salient example of the US, on whose final demand so much has for so long depended. Total private sector debt rose from 112 per cent of GDP in 1976 to 295 per cent at the end of 2008. Financial sector debt alone jumped from 16 per cent to 121 per cent of GDP over this period. How much of a reduction in these measures of leverage occurred in the crisis year of 2008? None. On the contrary, leverage rose still further.

The danger is that a turnround, however shallow, will convince the world things are soon going to be the way they were before. They will not be. It will merely show that collapse does not last forever once substantial stimulus is applied. The brutal truth is that the financial system is still far from healthy, the deleveraging of the private sectors of highly indebted countries has not begun, the needed rebalancing of global demand has barely even started and, for all these reasons, a return to sustained, private-sector-led growth probably remains a long way in the future. (Martin Wolf, “Why the ‘green shoots’ of recovery could yet wither, Financial Times)

Debt is at the very center of the current financial crisis. The massive debt-overhang can only be resolved by writing down losses, restructuring capital, and initiating debt-relief programs. The Fed and Treasury’s task is to soften the effects of a hard landing not to stop the process altogether. That would be pointless. Recessions are a necessary purgative that cleanse the system of waste and excess. Wall Street’s unprecedented credit expansion — which ballooned to gigantic proportions from fetid assets, off-balance sheet operations and mega-leveraging — ensures that this recession will be more agonizing than any before. But that just makes it all the more important. The system has to exhale before the patient can be revived.