“I’m so damn average that what I write resonates with people”, Joe Bageant once told an interviewer in explaining how he had gained a global following for his essays published on the web. In 2004, at the age of 58, Joe sensed that the Internet could give him editorial freedom. Without gatekeepers, he began writing about what he was really thinking, and then submitted his essays to left-of-center websites.

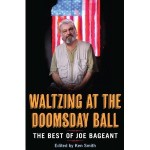

Joe Bageant died in March 2011, having written two books, and 78 essays that were posted on his own website and also on many other sites. The 25 essays reproduced in this book were first published on the web. I’ve selected them based on many emails from readers, web traffic counts, and specific suggestions from his online colleagues. They appear here as Joe wrote them, apart from copy-editing and light corrections agreed to between me and his book editor, Henry Rosenbloom, the publisher at Australia’s Scribe Publications.

Joe began writing for various publications in his twenties. He once told me how happy and proud he was when he sold his first article to the Colorado Daily, unashamedly recalling how he got tears in his eyes as he looked at a check for $5. It was only five dollars, but it was proof that he had become a professional writer. Joe freelanced articles for a dozen years, mostly writing about music, but also writing profiles of people such as Hunter S. Thompson, Timothy Leary, and G. Gordon Liddy. With a family to support, Joe found work as a reporter and columnist for small daily newspapers. Then, for two decades, Joe submerged his rage and natural writing style while working at various hard-labor jobs, before working again as a newspaper reporter, and then as an editor of magazines — one in military history and before that a magazine that promoted agricultural chemicals.

At the age of 17, Joe enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving on an aircraft carrier. Joe had farmed with horses for several years, tended bar, and considered himself at times to be a “Marxist and a half-assed Buddhist.” Always wanting to escape, he embarked on a life-long voyage of discovery that included living in a commune and on an Indian reservation, and, later in life, in Belize and in Mexico.

Joe often said that the Internet allowed him to find his voice. But I would argue that Joe always had his voice, and that what the Internet did for him was to permit him to find a readership. Once his essays started appearing on various websites, Joe soon gained a wide following for his forceful style, his sense of humor, and his willingness to discuss the American white underclass, a taboo topic for the mainstream media. Joe called himself a “redneck socialist,” and he initially thought most of his readers would be very much like himself — working class from the southern section of the U.S.A. So he was pleasantly surprised when emails started filling his in-box. There were indeed many letters from men about Joe’s age who had also escaped rural poverty. But there were also emails from younger men and women readers, from affluent people who agreed that the political and economic system needed an overhaul, from readers in dozens of countries expressing thanks for an alternative view of American life, from working-class Americans in all parts of the country, and more than a few from elderly women who wrote to Joe to say that they respected and appreciated his writing, but “please don’t use so much profanity”.

The central subject of Joe’s writing was the class system in the United States, and the tens of millions of whites ignored by coastal liberals in New York, Washington, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. In his online essays and books, and also in conversations over beer or bourbon, Joe would rail against the elite class who looked down on his people — poor whites, the underclass, rednecks. Joe was amused that a New York book editor once said to him, “It’s as if your people were some sort of exotic and foreign culture, as if you were from Yemen or something.”

The central subject of Joe’s writing was the class system in the United States, and the tens of millions of whites ignored by coastal liberals in New York, Washington, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. In his online essays and books, and also in conversations over beer or bourbon, Joe would rail against the elite class who looked down on his people — poor whites, the underclass, rednecks. Joe was amused that a New York book editor once said to him, “It’s as if your people were some sort of exotic and foreign culture, as if you were from Yemen or something.”

Joe spent almost as much time answering emails as he did writing essays. Often a response to an email would be rewritten and included in his next essay, and Joe would send thanks to the reader for providing the spark. In the six years that Joe was writing for publication on the web, he answered thousands of emails from readers — sometimes with just one sentence, but often churning out a thousand words or more.

He and I would talk about the response he was getting to his writing. His explanation was that he was the same as his reader friends, ordinary and fearful. “I don’t write to them,” Joe said in an email to one of his readers. “I don’t write for them. And I don’t write at them. We merely live on the same planet watching the unnerving events around us, things the majority does not seem to see. So I write about that. And maybe for just a moment, a few friends I’ve never met do not feel so alone. Nor do I.”

I first met Joe only seven years before he died, but it seems as though I had known him all of my life. I learned later that there were many people who had similarly become friends of Joe, meeting first by email, then by phone, and then often making personal visits to his home in Virginia, or Belize, or Mexico.

In 2004, I was living in Nice, France and had read one of Joe’s online essays. I sent him an email praising his style and ideas. He replied with a thank-you note, asking if I were wealthy and why I, an American, was living in France. I explained that I lived frugally in a working-class neighborhood of Nice, eating and shopping where the locals did. That started an email exchange and then many phone calls. In one conversation, he said he was bone tired from a daily three-hour commute to a job he didn’t really like. I told him that he should take a couple of weeks off and come to France. He did just that.

Joe arrived at the Nice airport with a back-pack and his guitar. We went on daily walking tours of Nice, to my favorite bistros and some historical spots, and I introduced Joe to many of my friends. Joe had been there about a week when he said he wanted to explore the city on his own — my tour-guide services were not needed. I reminded Joe that he didn’t speak a word of French and he might get lost, so I gave him a note to show a taxi driver how to get back to my apartment. Joe had said he would be gone about two hours, but it was eight hours later that he returned. He had somehow found a beer bar where French taxi drivers met after work, and had spent the day arguing about politics and the global economy. Joe explained that one of the taxi drivers spoke English and had served as a translator. I like this anecdote because it illustrates how comfortable Joe was with working people, no matter what language they spoke. This ease of meeting and befriending working people was repeated in Mexico, where shopkeepers, gardeners, and taxi drivers would soon treat Joe as a long-lost brother.

It was during this visit to France that I convinced Joe he needed his own website, if for no other reason than to serve as an archive for his essays, which were then scattered all over the web. I told him that I would get it started and teach him how to post to it. But in seven years Joe did not post anything, never once logged onto the server, and kept asking me to do it. He would rarely look at his own website, even when I asked how him he liked changes I had made. It was not that Joe was a Luddite, ignoring the Internet. He spent hours every day reading other websites and answering emails. But when it came to his own site he was humble, almost embarrassed, by the focus on him personally. “I hate this me-me-me stuff,” he would say. He was reluctant to have news about himself posted, dragging his feet whenever I suggested that news about his books be posted. He finally agreed that I could write about him and put my name as a tag at the bottom of a post.

I left France five years ago when the dollar/euro exchange rate made it too expensive for me. Eventually, I moved to Mexico. Joe came to visit, and he liked the lifestyle, the Mexican people, and the low cost of living. He stayed in my second bedroom for a couple of months, then got his own place. Joe’s wife visited several times a year, and had discussed moving to Mexico when she retired.

While living in Mexico, Joe wrote his second book, Rainbow Pie: A Redneck Memoir, which was released in the U.S. just four days after his death. I wish there were a video of Joe writing this book. He worked on a three-quarter-size notebook, typing fast and furiously with two index fingers, with a burning but unsmoked cigarette in a nearby ashtray.

Between France and Mexico, I had stayed with Joe and his wife, Barbara, in Winchester for a couple of months to help with the editing and proofing of the final manuscript of Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches from America’s Class War. While in Winchester, I met many of Joe’s old friends, some of whom had known him since childhood. This helped me gain an additional understanding of the scorn and condescension of the town’s elites toward Joe and his underclass, the poor whites. In addition to his friends, I also met more than a few people who knew Joe but had few kind words to say about him because of his left-wing politics and what they felt was the negative picture he painted of the town. Not only was he rejected by the affluent class, but also by some of the very people he was trying to help — including some people he had grown up with.

The fact that Joe was gaining recognition in other countries did not register with the locals in Winchester. Joe did not consider himself a Christian, so he might object to my citing Jesus’s saying that a prophet is not recognized in his own land. While declaring that such a lofty Biblical aphorism would not apply to a redneck, Joe might also have cited the reference in its entirety, chapter and verse.

The sad fact is that Joe was not recognized in his own small home-town of Winchester, Virginia, with its population of 25,000, even though he was certainly the area’s most widely published contemporary writer. His hometown newspaper, The Winchester Star, never mentioned his name — not even when he was signed by Random House for his first book, Deer Hunting with Jesus, nor when the book was getting rave reviews in other countries. Joe would never admit to being bothered by the local newspaper ignoring him and his success, but it was obvious to those who knew him that he would have appreciated some local recognition. He dismissed this slight by explaining that the newspaper’s publisher was still angry from decades before when Joe worked briefly as a reporter for the Star and tried to organize a union for the editorial staff.

Even though neither Joe’s hometown newspaper nor any mainstream U.S. newspaper or news service noticed his death, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation replayed an interview from his book tour a year before. And La Stampa, one of the largest and most prestigious newspapers in Italy, published an obituary and another glowing review of the Italian edition of Deer Hunting with Jesus.

Looking back now, it is clear that Joe’s energy was being sapped in the months before his cancer was diagnosed. Just three days before a massive and inoperable abdominal tumor was discovered, Joe had spent the day riding a horse with Mexican cowboys. But, for a month or two before this, he was finding it increasingly difficult to concentrate sufficiently to finish an essay. I didn’t see it at the time. His last essay, “AMERICA: Y UR PEEPS B SO DUM”, took Joe more than a month to write, in fits and starts. He emailed me a draft of this essay, which was more than 8,000 words — long even for Joe. I cut about 3,000 words from the draft, re-arranged chunks of text, and sent it back to Joe with a note that the draft could potentially be one of his best essays, but that it was a jumble of thoughts and he needed to sweat blood while re-writing it. Rather than coming back with a typically argumentative response, Joe agreed and replied that he would do more work on it. Now I feel guilty about having pushed a sick and dying man to be creative, even though neither Joe nor anybody else knew how ill he really was. But I try not to feel too bad about it, because I think it is indeed one of his best essays.

Things are often more clear in retrospect. One book that Joe often referred to in conversations was Dark Ages America: The Final Phase of Empire by Morris Berman. As it happened, Joe and I had both independently been corresponding with Berman, and we learned that Berman was also a sixtyish American expat living in Mexico, just a mountain range to the east of us. Joe and I had been planning to invite ourselves to visit Berman, but it didn’t happen. Berman wrote a review of Rainbow Pie, and he summed up Joe with a phrase that had never occurred to me, nor probably to Joe either. Berman wrote that the source of Joe’s frustration was “extreme isolation”, adding that Joe realized the U.S. was the greatest snow job of all time, likening the country to a hologram, “in which everyone in the country was trapped inside, with no knowledge that the world (U.S. included) was not what U.S. government propaganda, or just everyday cultural propaganda, said it was. He watched his kinfolk and neighbors vote repeatedly against their own interests, and there was little he could do about it.”

On his last day, with his family gathered around his bed, Joe said: “Dying isn’t as bad as I thought it was going be. I’m just going into this blank space where there’s nothing.”

That’s not quite true, Joe. Your books and essays remain with us, and through them you are still alive. Goodbye, good friend.