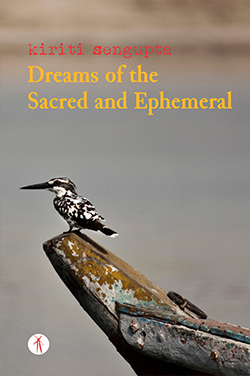

Among the many books I’d bought this year from the International Kolkata Book Fair there were three titles that connected me to Kiriti Sengupta: the two books he authored and the other was Appraisals: Breaking the Barriers (edited by Sunil Sharma & Dustin Pickering), a collection of the critiques of Sengupta’s many books. I read Appraisals first to understand what others had to say about him, and then I approached Dreams of the Sacred and Ephemeral, a poetic trilogy, published by Hawakal (2017). As reviewer I had two choices, i) to think likewise and read him comparing his works with other great poets, ii) go totally blank, unlearn everything I’ve read, and then re-read Sengupta as he is. I chose the second way. I love reading poetry and being a voracious reader I prefer talking about my own perception.

In Dreams of the Sacred and Ephemeral the very first thing that impressed me was “Alap,” the introductory chapter, written atypically. Very wisely Sengupta said, “A harmonious relationship between two people in India starts with a formal alap.” Frankly, this concept of connecting through a more relevant and informal Indian approach is alluring and I was drawn into the book further. It is true that reading a monotonous formal introduction with a lot of hype and hoopla tires one to the core at the very beginning, and I’m sure many readers don’t read the foreword and introduction segments of a book. And then, as Sengupta said, “there’s no fight between the class and the mass, and one must remember a ‘class’ essentially belongs to the ‘mass’”—made me realize the author better.

In Dreams of the Sacred and Ephemeral the very first thing that impressed me was “Alap,” the introductory chapter, written atypically. Very wisely Sengupta said, “A harmonious relationship between two people in India starts with a formal alap.” Frankly, this concept of connecting through a more relevant and informal Indian approach is alluring and I was drawn into the book further. It is true that reading a monotonous formal introduction with a lot of hype and hoopla tires one to the core at the very beginning, and I’m sure many readers don’t read the foreword and introduction segments of a book. And then, as Sengupta said, “there’s no fight between the class and the mass, and one must remember a ‘class’ essentially belongs to the ‘mass’”—made me realize the author better.

This humble take on the fundamentals and the apparent simplicity of the language don’t obscure the profundity and importance of the conclusion Sengupta reached. Another thing that attracted me was the amalgamation of the two literary genres which enhances their respective purposes, making the effects stronger at places of their fusion. We know what poetry is, and what to expect from its line allegiance, but in prose if the essence is kept unaltered, it is pure diligence. And when a book has the flavors of both prose and poetry, it not only shows the proficiency of the author-poet (I’d prefer addressing Sengupta as such), but the book also coaxes me as reader to flex my perception beyond its limit. In the exuberance of judging and finding flaws, to see whether Sengupta has done equal justice to both forms, I read and reread Dreams of the Sacred and Ephemeral.

The language is simple; however, fathoming the depth needs patience and homogeneity of mind. This collection has a magical aura about it. The first two sections of this trilogy consist of a mix of prose and poetry, each prose is pretty much like a muse, the mapping of a few incidents in prose that leads to a verse. The interweaving is laudable. I’d like to focus on the conceptualization of various aspects of life, its expressions and objectives. In this deeply compassionate, thoughtful and eloquent work author-poet Kiriti Sengupta shares his profoundly human vision, creating a common core that changes readers’ notions about different facets of life. The first section, My Glass of Wine, has confessions and narrations of Sengupta’s chanced encounters, his experiences and his explorations of different places of India and their influences on him. In “As I Traversed” he confesses about an embarrassment which introduced him to literature. He writes about religious practices, highlighting ‘Baptism,’ ‘Tantra,’ ‘Qurbani,’ concluding that power, alcohol and blood are all the links or routes to prosperity that all religions, in one way or the other, have been associating with divinity.

Whispers the tale of your character,

color and its fragrance merge to call it

a Rose.

A lot matters,

if you remember

the name… (“Namesake”)

I loved the way Sengupta says name has a sensory impact; names can render tantalizing images to things or people even without seeing them. In India people are named according to their complexion (skin), physical attributes, season and place of birth, etc. Like a baby girl born with beautiful eyes may be named ‘Sunayana,’ ‘Sunetra,’ or ‘Nayanika.’ Without meeting people our minds can envision them, just the way the very mention of rose brings its essence and beauty.

Faulty are my limbs,

they tilt even on the steady floor;

I readily realize

it is all in my mind

as the sky swings. (“The Encyclopedia”)

This is a poem that brings forth the awareness of acceptance. We might think that whatever we have learnt until now is all we are expected to know. However, there is much to learn and explore beyond our understanding. And, it’s our shortsightedness that prevents us from accepting unknown things.

Few beautiful scratches, deep within,

soft marks, palpable even after months; (“Scratches only are Human”)

This unfolds the softer side of Sengupta’s persona. It’s absurd considering men to be insensitive and indifferent. In “Clarity” he tells that clarity lies in simplicity, be it life or poetry. It is much like the process of making ghee from churned milk, the steps are easy yet strategic.

Healers worry about the front;

it is dusty, empty, but advocates

spiritual pursuits (“Unravel”)

These lines focus on a more pragmatic approach to one’s inner-self. Sengupta says that at times anxiety and introspection can consume the older perspectives and one’s identity totally, or nudge the soul to open up to a newer vision.

With each verse I can see Sengupta’s growth, his transformation from a dental surgeon to a poet; a journey from profession to passion.

The second section, The Reverse Tree, touches more serious and deeper aspects of life, like spiritual evolution, assumptions, human sexuality and orientation. Here we come across a new person who is bold and confident. Honestly, the title seemed a little absurd before I read this section. “The Reverse Tree”—is this a title? I thought. I’ve marked the frontispiece poem:

my tree is stout,

well-developed

it refutes the gravitational pullnot always, you know…

my roots run

against the sap!

Frankly, not a speck of this attitude and exclamation remained after I finished reading this section. Touching a subject on sexuality and striking a chord without creating a controversy seems impossible, yet Sengupta had the guts to take up this challenge. Sexuality is a confusing subject, and at the same time intriguing. His effortless dealing with it and explaining the coexistence of both feminine and masculine traits in each human body unearthed the strength of character he holds. Sengupta also tells about the existence of a third sex, a transgender. His chanced meeting and interactions with Lara played a pivotal role in his knowing the third sex more extensively. Although India does not approve homosexuality, Sengupta openly advocates that even the Vedic literature accepted the existence of third sex, the Tritiya Prakriti. He objects to the bias of considering them as “grey,” and refutes the ideology of considering this an abnormality. In “Crisis” author-poet Sengupta’s intention was not to expose but to explore this layer of the human psyche—various dimensions of human nature and breaking the societal taboos the babus and pundits always wanted to keep under wraps.

my he throbs in fire

while my she is coy

Ahoy! This is the ultimate power of words and imagination which has obliterated many inhibitions about sexuality authoritatively. Also in this section I came across sentimental issues and other values of the human mind. There is a total reversal of sprouting thoughts of the unknown, unaccepted, uncharted, undeciphered. There is uprooting of deep-seated orthodox doctrines and boxed mindset. Thus, the title The Reverse Tree is justified.

The concluding section, Healing Waters Floating Lamps, has only poems. They have a spiritual and mystique touch! That’s what others say. Mystic—yes, and perhaps, much deeper than that.

I reach the sky

While I draw a circle in the waterLooking at the image

I take a dip (“Beyond the Eyes”)

Here I find more science than spirituality. As reader the poem took me to an infinite realm where the existing energies on the earth merge with the universe. Energy moves in circle. It changes only in form. I find similarities with the law of Thermodynamics that states energy can neither be created nor destroyed. Everything that is not a part of the system constitutes its surroundings. The system and surroundings are separated by boundaries, each interchangeable.

‘’After Bath’’ has been interpreted as a ‘soul call,’ the river playing as a medium of unison for the body and soul, cleansing the tears and fears. Yes, I have read this poem as it has been explained as such by senior poets. However, I think Sengupta has a different take here. If one wants to cleanse body, why would one mention “afternoon?” Holy, sanctifying dips are taken in early morning or at sun-set. Here he refers to the time of the day when the water remains highly polluted; Sengupta doesn’t bother to take a holy plunge into the Ganges considering it pious as others may consider. He can’t overcome the fear of getting mainstream; he knows neither the Ganges nor the beliefs can be purified.

O Sun, I remember

I’ve bathed your feet with the water of the Ganges… (“After Bath”)

As if Sengupta is advising, who will purify whom depends on the strength of one’s character. To sanctify or smear lies in our mortal hands. In “In Dusty Feet” Sengupta says he has tried to follow the course as others—in the pious company of the Guru, seeking his blessings, gaining knowledge, and to reach the ultimate. However, at the end this knowledge failed to show him the path he was looking for, God was made smaller than he had assumed, the path wasn’t as easy as he presumed.

Some poems from the earlier two sections have been repeated here, but as each one has layered meanings, I tried perceiving each again from other angles. Not taking them as mimesis and pragmatic, I tried looking into the objectivity of these poems. I read “Unravel’’ again,

Healers worry about the front;

it is dusty, empty, but advocates

spiritual pursuitsMy Master enjoys the stage—

looking at the sparkling crowd he tells:

“Reach the void, and see the cage! (“Unravel”)

I had read it as a spiritual poem in the first place, advocating spirituality as the ultimate way to salvation, now I can find sarcasm in it. As if Sengupta tried to convey, some people can be happy with their present prosperity, some think these are only temporary and permanent happiness lies in spirituality. As a matter of fact, human beings can never become free and happy. Achieving everything or giving up on all will never satisfy man, as the mind is in habitual unrest and encaged in discontent.

So organic is my memory—

The granular residue lifted us to heaven

Ah! Pious Ghee, and incorrigible! (“Clarity”)

Clarity lies in simplicity and deliberation, but on a second reading I felt the poem tells about our inclination to stay close to the roots, our happiness lies in the essence of past memories of childhood, the more we excel and higher we rise, the more we long to roll back time.

Thus, I feel the poems in Dreams of the Sacred and Ephemeral are more intense and layered than they appear to be. It is true that with time and age life opens a new page to everyone; our relationships are phrased and rephrased through incidences and experiences in life. I must confess that after a long period of time I have read something as mystically layered as this book. It has made me stay with the same book in my hands for five consecutive days, reading, re-reading and understanding what lies underneath the lines, never feeling a bit exhausted. If time permits, I’ll love to read the book one more time.