During World War II, Japan’s imperialist military invaded Northeast China and afterward spread throughout Southeast Asia, then on to an ill-fated attack on Pearl Harbor. Japanese crimes were many during the war and included the coerced services of ianfu (comfort women) for Japanese troops, slave labor, and experimentation on living humans.

Today Japanese right-wingers clamor for a re-expansion of Japanese militarism; prime minister Abe Shinzo pays visits to a shrine venerating Japanese dead — among them war criminals; the Diet demonstrates belligerence toward North Korea, a country Japan had formerly occupied; Okinawans’ (Japanese living on the southern archipelago) call for the removal of US military bases goes unheeded; and Japanese grapple with racism still rife toward ethnic Koreans in Japan. The current status post-WWII is not pretty and does not bode well for a Japan aspiring to a permanent United Nations Security Council seat.

Chinese seem particularly well-informed about the situation in Japan albeit biased.

A few months back, a neighbor in Harbin expressed her disdain for the Japanese prime minister Abe Shinzo. This was in response to Abe having visited Tokyo’s Yasukuni shrine, which houses the kami (spirits) of Japanese war criminals. Such is the palpable acrimony still felt by many Chinese people toward Japan. The criticism of Japan is widespread, but seems especially strident among all age groups in the northeastern city of Harbin – understandably so.

Seeking a better understanding for the animosity, I boarded the 338 bus in the Nangang district of Harbin and headed south to Ping Fang on the outskirts of Harbin. I asked the bus driver to inform me when we reached the stop for the Unit 731 Museum, founded on the site where many Japanese war crimes took place. The Japanese dissembled Unit 731 as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army (the Imperial Japanese Army of that WWII era), which was set up on secret decree from Japanese emperor Hirohito. ((Yang Yanjun, Japan’s Biological Warfare in China (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 2016): 13.))

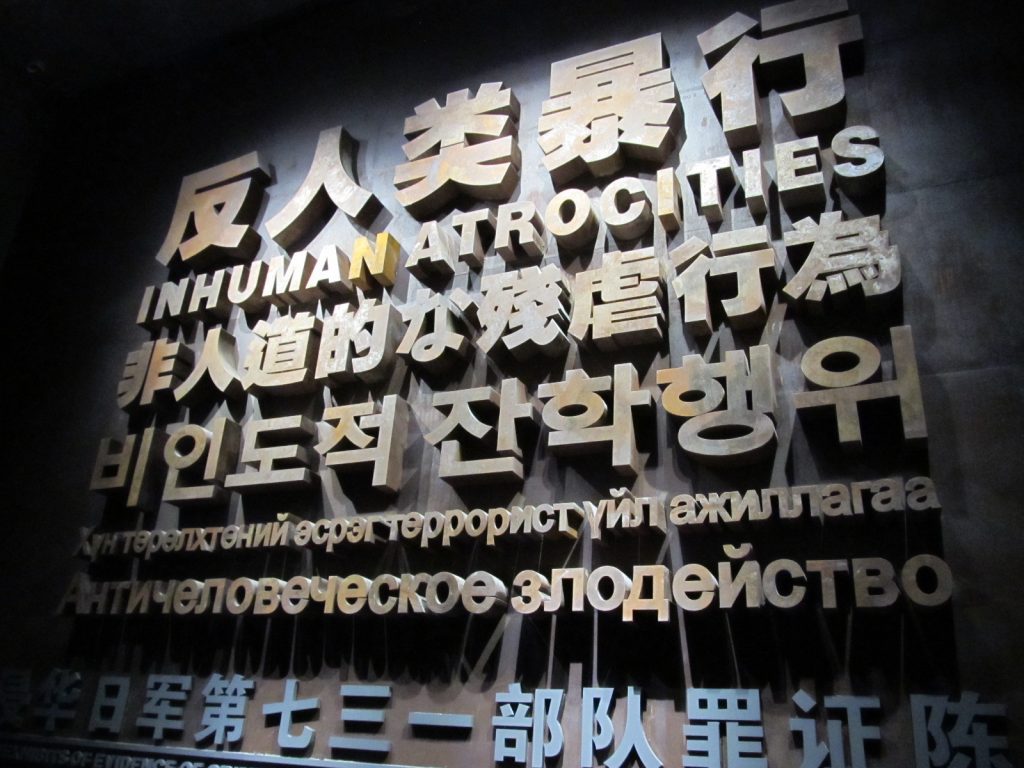

After alighting the bus, I walked down a side street and came to a gravel field surrounded by barbed wire fencing; in the near distance stood the ruins of Unit 731’s boiler. I crossed the gravel field to see the ruins close up and then proceeded to the Exhibition Hall of Evidence of War Crimes by Japanese Army Unit 731 (Unit 731 Museum). The museum opened to the public on 15 August 2015; admission is free and translations of the evidence are available in English, Japanese, Korean, and Russian.

The museum’s darkened entrance to the exhibits features an imposing spotlighted stone wall informing the visitor that evidence of inhuman atrocities lies beyond.

I was aware of Japanese World War II crimes and atrocities in China, having visited the Nanjing Massacre Hall in 2003. There the number 300000 is on bold display for the claimed number of victims. The memorial hall’s evidence drives home the horrors that the late author Iris Chang wrote of in her book, The Rape of Nanking.

Inside the Unit 731 Museum, visitors will see evidence of biological and chemical weapons experiments that used squirrels, rats, fleas, and humans as guinea pigs. Clearly such experiments constituted insidious forms of torture. The victims were mainly Chinese, but included Koreans and Russians, and even some Americans. To the Japanese, however, their victims were not humans; they were maruta (logs).

The physician-/torturer-in-charge was lieutenant-general Ishii Shiro whose name has not been accorded the widespread infamy of the German SS physician/torturer Josef Mengele. Proceeding further in the museum, a photo captured my attention. There were six rows of people, men and women of the Training and Education division of Unit 731. Much as one might have no difficulty envisioning horns and a piked tail attached to Ishii, the everydayness of these people quite embodies the banality of evil. These Japanese were associated with the freezing, gassing, infecting, and live vivisection of maruta.

The prisoners were infected with 29 major species of bacteria such as typhoid, plague, anthrax, and cholera. Plague rats were bred, as well as plague-bearing fleas, and these were dropped onto Chinese villages and the results recorded. At other times, prisoners were bound to wooden crosses in a clearing to which ceramic, poison gas-filled canisters were dropped from the sky.

The experiments/tortures included freezing prisoners in various states of undress to determine optimal thawing methods.

Another shocking exhibit was of an airtight cubicle in which two frightened, young girls were clinging to each other. Outside the cubicle stood four Japanese observing and recording the effects of the poison gas experiment. These experiments were repeated until the victims died.

The most grotesque experiments were vivisections performed on living humans, usually without anesthesia. The victims were strapped down and their mouths were stuffed with medical gauze to stifle their screams. ((Ibid, 57.))

Despite such grotesquerie, the 731 Museum exhibits are displayed in a thoroughly restrained manner. The intent is not to shock or repulse visitors, rather it is to inform. Japanese war criminals have testified to this. Yutaka Mitsuo, formerly with a Japanese military police in Dalian, said, “The Chinese government has adopted a merciful and lenient attitude toward Japanese war criminals – that is, to hate the crimes rather than the sinners.” ((Ibid, 50.))

Conversely, the Japanese government has endeavored to cover up the war crimes. Japan has neither acknowledged nor apologized for the war crimes committed by Unit 731.

At the end of WWII, the Japanese were forced to destroy and flee their 100 biological and chemical weapons facilities in 19 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions of China. ((Ibid, 109.)) The razed facilities left behind a ticking time bomb of plague for the Chinese. ((Ibid, 110-112.))

The United States was fully complicit in the cover up of Unit 731. In exchange for turning over documentation on Unit 731’s experiments, the US agreed to protect the Japanese war criminals from prosecution. Edward Hill, an American investigating Japanese biological warfare remarked of the research data obtained from Unit 731: “Such information could not be obtained in our own laboratories because of scruples attached to human experimentation.” ((Ibid, 133.)) [emphasis added] Apparently such scruples did not apply to skirting justice to obtain the morbid information. The US cover-up has been criticized for “sacrificing and sabotaging the interests of China and the Soviet Union.” ((Ibid, 143.))

The Unit 731 Museum serves an educative function. The atrocities are meant to deter future war crimes and promote peace. The Unit 731 Museum is also a testament to a dark epoch in Japanese history for which the country has never taken responsibility. Having lived a number of years in Japan, my experience is that most Japanese are unaware of war crimes committed in WWII. The Japanese government’s elision of this shameful history has been effective. In 2010, a questionnaire given to Japanese medical students in Tokyo found that 62% knew nothing about Unit 731. ((Ibid, 179.)) That is, these students knew nothing of the sordid history in which the Japanese medical establishment was deeply involved.

The present generation of Japanese did not commit the crimes. These sordid crimes belong to their ancestors. However, until Japanese society does what is right and just by its past victims, the war crimes will endure as a historical and present-day blight on Japan. Until Japan deals forthrightly with its unatoned-for militarism, the stain of war crimes will linger. ((I write as a Canadian passport holder who resides in China. The present generation of “Canadians” did not commit the ethnic cleansing and extirpation of Turtle Island’s Indigenous peoples (albeit the racist attitudes and crimes continue on a lesser scale), but the genocide still demands political and societal atonement. For elaboration, see Kim Petersen, “Biological Warfare in the Pacific Northwest,” Dissident Voice, 29 July 2013. See also Robert Davis and Mark Zannis, The Genocide Machine in Canada: The Pacification of the North (Montreal: Black Rose, 1973); Tom Swanky, The Smallpox War in Nuxalk Territory (Lulu Press, 2016); James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (University of Regina Press, 2013).))

Conclusion

Unit 731 Museum presents a conclusion, upon which I can not improve:

The exhibits of crime evidences of Unit 731 publically demonstrate the historical facts and crimes of Japanese biological warfare and Unit 731. The objective of disclosing its war crimes, responsibility and post-war damages to a full extent is to arouse awareness and remembrance of the history, from which lessons can be learnt, and deep reflection can be made about the relationship between war and medical science, war and conscience, as well as war and peace. From there, we should also learn how to respect human rights and freedom, in pursuit of peace and a civilized world.