Dr. Gus Abu-Sitta is the head of the Plastic Surgery Department at the AUB Medical Center in Lebanon. He specializes in: reconstructive surgery. What it means in this part of the world is clear: they bring you people from the war zones, torn to pieces, missing faces, burned beyond recognition, and you have to try to give them their life back.

Dr. Abu-Sitta is also a thinker. A Palestinian born in Kuwait, he studied and lived in the UK, and worked in various war zones of the Middle East, as well as in Asia, before accepting his present position at the AUB Medical Center in Beirut, Lebanon.

We were brought together by peculiar circumstances. Several months ago I burned my foot on red-hot sand, in Southeast Asia. It was healing slowly, but it was healing. Until I went to Afghanistan where at one of the checkpoints in Herat I had to take my shoes off, and the wound got badly infected. Passing through London, I visited a hospital there, and was treated by one of Abu-Sitta’s former professors. When I said that among other places I work in Lebanon, he recommended that I visit one of his “best students who now works in Beirut”.

I did. During that time, a pan-Arab television channel, Al-Mayadeen, was broadcasting in English, with Arabic subtitles, a long two-part interview with me, about my latest political/revolutionary novel “Aurora” and about the state of the global south, and the upsurge of the Western imperialism. To my surprise, Dr. Abu-Sitta and his colleagues were following my work and political discourses. To these hardened surgeons, my foot ‘issue’ was just a tiny insignificant scratch. What mattered was the US attack against Syria, the Palestine, and the provocations against North Korea.

My ‘injury’ healed well, and Dr. Abu-Sitta and I became good friends. Unfortunately I have to leave Beirut for Southeast Asia, before a huge conference, which he and his colleagues are launching on the May 15, 2017, a conference on the “Ecology of War”.

I believe that the topic is thoroughly fascinating and essential for our humanity, even for its survival. It combines philosophy, medicine and science.

What happens to people in war zones? And what is a war zone, really? We arrived at some common conclusions, as both of us were working with the same topic but looking at it from two different angles: “The misery is war. The destruction of the strong state leads to conflict. A great number of people on our Planet actually live in some conflict or war, without even realizing it: in slums, in refugee camps, in thoroughly collapsed states, or in refugee camps.”

We talked a lot: about fear, which is engulfing countries like the UK, about the new wave of individualism and selfishness, which has its roots in frustration. At one point he said: “In most parts of the world “freedom” is synonymous with the independence struggle for our countries. In such places as the UK, it mainly means more individualism, selfishness and personal liberties.”

We talked about imperialism, medicine and the suffering of the Middle East.

Then we decided to publish this dialogue, shedding some light on the “Ecology of War” – this essential new discipline in both philosophy and medicine.

Ecology of War

(The discussion took place in Beirut, Lebanon, in Cafe Younes, on April 25, 2017)

Broken Social Contract In The Arab World, Even In Europe

GA-S: In the South, medicine and the provision of health were critical parts of the post-colonial state. And the post-colonial state built medical systems such as we had in Iraq, Egypt and in Syria as part of the social contract. They became an intrinsic part of the creation of those states. And it was a realization that the state has to exercise its power both coercively, (which we know the state is capable of exercising, by putting you in prison, and even exercising violence), but above all non-coercively: it needs to house you, educate you, and give you health, all of those things. And that non-coercive power that the states exercise is a critical part of the legitimizing process of the state. We saw it evolve in 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. So as a digression, if you want to look at how the state was dismantled: the aim of the sanctions against Iraq was not to weaken the Makhabarat or the army; the aim of the sanctions was to rob the Iraqi state of its non-coercive power; its ability to give life, to give education, and that’s why after 12 years, the state has totally collapsed internally – not because its coercive powers have weakened, but because it was robbed of all its non-coercive powers, of all its abilities to guarantee life to its citizens.

AV: So in a way the contract between the state and the people was broken.

GA-S: Absolutely! And you had that contract existing in the majority of post-colonialist states. With the introduction of the IMF and World Bank-led policies that viewed health and the provision of health as a business opportunity for the ruling elites and for corporations, and viewed free healthcare as a burden on the state, you began to have an erosion in certain countries like Egypt, like Jordan, of the non-coercive powers of the state, leading to the gradual weakening of its legitimacy. Once again, the aim of the IMF and World Bank was to turn health into a commodity, which could be sold back to people as a service; sold back to those who could afford it.

AV: So, the US model, but in much more brutal form, as the wages in most of those countries were incomparably lower.

GA-S: Absolutely! And the way you do that in these countries: you create a two-tier system where the government tier is so under-funded, that people choose to go to the private sector. And then in the private sector you basically have the flourishing of all aspects of private healthcare: from health insurance to provision of health care, to pharmaceuticals.

AV: Paradoxically this scenario is also taking place in the UK right now.

GA-S: We see it in the UK and we’ll see it in many other European countries. But it has already happened in this region, in the Arab world. Here, the provision of health was so critical to creation of the states. It was critical to the legitimacy of the state.

AV: The scenario has been extremely cynical: while the private health system was imposed on the Arab region and on many other parts of the world, in the West itself, except in the United States, medical care remains public and basically free. We are talking about state medical care in Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

GA-S: Yes. In Europe as part of the welfare state that came out of the Second World War, the provision of healthcare was part of the social contract. As the welfare state with the advent of Thatcherism and Reagan-ism was being dismantled, it became important to undergo a similar process as elsewhere. The difference is that in the UK, and also in countries like Germany, it was politically very dangerous. It could lead to election losses. So the second plan was to erode the health system, by a thousand blows, kill it gradually. What you ended up in the UK is the piece-by-piece privatization of the health sector. And the people don’t know, they don’t notice that the system is becoming private. Or in Germany where actually the government does not pay for healthcare – the government subsidizes the insurance companies that profit from the private provision of healthcare.

AV: Before we began recording this discussion, we were speaking about the philosophical dilemmas that are now besieging or at least should be besieging the medical profession. Even the social medical care in Europe: isn’t it to some extent a cynical arrangement? European countries are now all part of the imperialist block, together with the United States, and they are all plundering the rest of the world – the Middle East, Africa, parts of Asia – and they are actually subsidizing their social system from that plunder. That’s one thing. But also, the doctors and nurses working for instance in the UK or Germany are often ‘imported’ from much poorer countries, where they have often received free education. Instead of helping their own, needy people, they are actually now serving the ageing and by all international comparisons, unreasonably spoiled and demanding population in Europe, which often uses medical facilities as if they were some ‘social club’.

GA-S: I think what has happened, particularly in Europe, is that there is a gradual erosion of all aspects of the welfare state. Politically it was not yet possible to get rid of free healthcare. The problem that you can certainly see in the United Kingdom is that health is the final consequence of social and economic factors that people live in. So if you have chronic unemployment, second and third generation unemployment problem, these have health consequences. If you have the destruction of both pensions and the cushion of a social umbrella for the unemployed, that has consequences… Poor housing has health consequences. Mass unemployment has health consequences. Politically it was easy to get rid of all other aspects of the welfare state, but they were stuck with a healthcare problem. And so the losing battle that the health systems in the West are fighting is that they are being expected to cater to the poor consequences of the brutal capitalist system as a non-profit endeavor. But we know that once these lifestyle changes are affecting people’s health, it’s too late in terms of cure or prevention. And so what the European health systems do, they try to patch people and to get them out of the system and back on the street. So if you have children with chronic asthma, you treat the asthma but not the dump housing in which these children are living in. If you have violent assaults and trauma related to violence, you treat the trauma, the physical manifestation, and not the breakdown of youth unemployment, or racism that creates this. So in order to sustain this anomaly, as you said, you need an inflated health system, because you make people sick and then you try to fix them, rather than stopping them from being sick. Hence that brain drains that have basically happened, where you have more Ghanaian doctors in New York than you have in Ghana.

AV: And you have an entire army of Philippine nurses in the UK, while there is suddenly a shortage of qualified nurses in Manila.

GA-S: Absolutely! This is the result of the fact that actually people’s health ‘happens’ outside the health system. Because you cannot get rid of the health system, you end up having a bloated health system, and try to fix the ailments that are coming through the door.

Collapse Of The Health Care In The Middle East

AV: You worked in this entire region. You worked in Iraq, and in Gaza… both you and I worked in Shifa Hospital in Gaza… You worked in Southern Lebanon during the war. How brutal is the healthcare situation in the Middle East? How badly has been, for instance, the Iraqi peoples’ suffering, compared to Western patients? How cruel is the situation in Gaza?

GA-S: If you look at places like Iraq: Iraq in the 80’s probably had one of the most advanced health systems in the region. Then you went through the first war against Iraq, followed by 12 years of sanctions in which that health system was totally dismantled; not just in terms of hospitals and medication and the forced exile of doctors and health professionals, but also in terms of other aspects of health, which are the sewage and water and electricity plants, all of those parts of the infrastructure that directly impact on people’s lives.

AV: Then came depleted uranium…

GA-S: And then you add to the mix that 2003 War and then the complete destruction and dismantling of the state, and the migration of some 50% of Iraq’s doctors.

AV: Where did they migrate?

GA-S: Everywhere: to the Gulf and to the West; to North America, Europe… So what you have in Iraq is a system that is not only broken, but that has lost the components that are required to rebuild it. You can’t train a new generation of doctors in Iraq, because your trainers have all left the country. You can’t create a health system in Iraq, because you have created a government infrastructure that is intrinsically unstable and based on a multi-polarity of the centers of power which all are fighting for control of the pie of the state… and so Iraqis sub-contract their health at hospital level to India and to Turkey and Lebanon, or Jordan, because they are in this vicious loop.

AV: But this is only for those who can afford it?

GA-S: Yes, for those who can, but even in those times when the government had cash it could not build the system anymore. So it would sub-contract health provisions outside, because the system was so broken that money couldn’t fix it.

AV: Is it the same in other countries of the region?

GA-S: The same is happening in Libya and the same is happening in Syria, with regards of the migration of their doctors. Syria will undergo something similar to Iraq at the end of the war, if the Syrian state is destroyed.

AV: But it is still standing.

GA-S: It still stands and it is still providing healthcare to the overwhelming majority of the population even to those who live in the rebel-controlled areas. They are travelling to Damascus and other cities for their cardiac services or for their oncological services.

AV: So no questions asked; you are sick, you get treated?

GA-S: Even from the ISIS-controlled areas people can travel and get treated, because this is part of the job of the state.

AV: The same thing is happening with the education there; Syria still provides all basic services in that area.

GA-S: Absolutely! But in Libya, because the state has totally disappeared or has disintegrated, all this is gone.

AV: Libya is not even one country, anymore…

GA-S: There is not a unified country and there is definitely no health system. In Gaza and the Palestine, the occupation and the siege, ensure that there is no normal development of the health system and in case of Gaza as the Israelis say “every few years you come and you mown the lawn”; you kill as many people in these brutal and intense wars, so you can ensure that the people for the next few years will be trying to survive the damage that you have caused.

AV: Is there any help from Israeli physicians?

GA-S: Oh yes! Very few individuals, but there is…

But the Israeli medical establishment is actually an intrinsic part of the Israeli establishment, and the Israeli academic medical establishment is also part of the Israeli establishment. And the Israeli Medical Association refused to condemn the fact that Israeli doctors examine Palestinian political prisoners for what they call “fitness for interrogation”. Which is basically… you get seen by a doctor who decides how much torture you can take before you die.

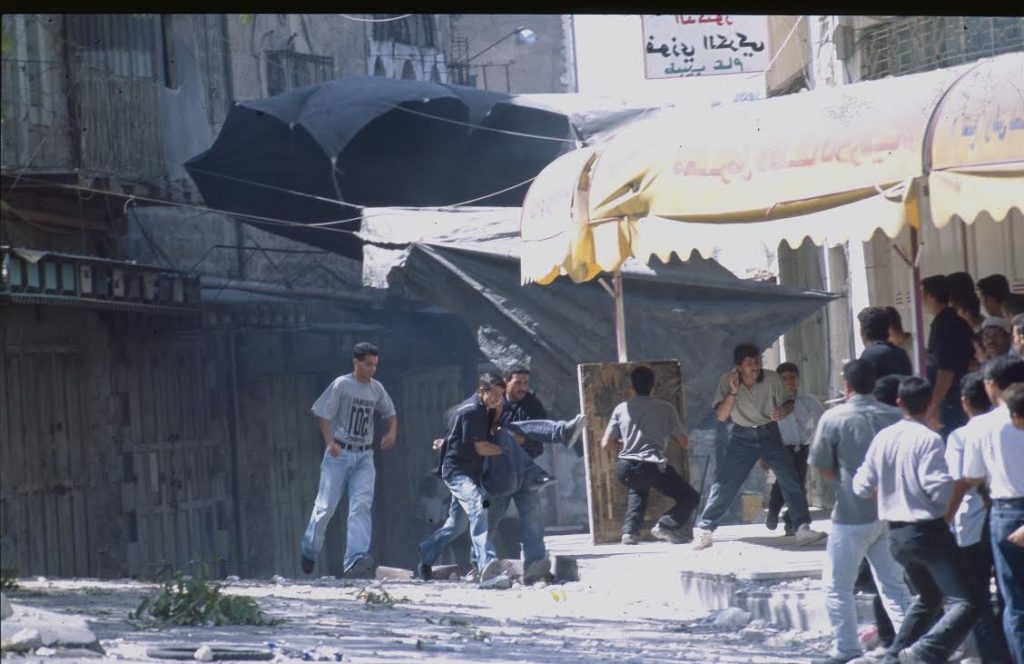

Gaza Shifa Hospital – wounded by Israeli soldiers

Gaza Shifa Hospital – wounded by Israeli soldiers

AV: This actually reminds me of what I was told in 2015 in Pretoria, South Africa, where I was invited to participate as a speaker at the International Conference of the Psychologists for Peace. Several US psychologists reported that during the interrogation and torture of alleged terrorists, there were professional psychologists and even clinical psychiatrists standing by, often assisting the interrogators.

GA-S: Yes, there are actually 2-3 well-known American psychologists who designed the CIA interrogation system – its process.

AV: What you have described that is happening in Palestine is apparently part of a very pervasive system. I was told in the Indian-controlled Kashmir that Israeli intelligence officers are sharing their methods of interrogation and torture with their Indian counterparts. And. of course, the US is involved there as well.

Conflict Medicine

GA-S: War surgery grew out of the Napoleonic Wars. During these wars, two armies met; they usually met at the frontline. They attacked each other, shot at each other or stabbed each other. Most of injured were combatants, and they got treated in military hospitals. You had an evolution of war surgery. What we have in this region, we believe, is that the intensity and the prolonged nature of these wars or these conflicts are not temporal-like battles, they don’t start and finish. And they are sufficiently prolonged that they change the biological ecology, the ecology in which people live. They create the ecology of war. That ecology maintains itself well beyond of what we know is the shooting, because they alter the living environment of people. The wounds are physical, psychological and social wounds; the environment is altered as to become hostile; both to the able-bodied and more hostile to the wounded. And as in the cases of these multi-drug-resistant organisms, which are now a big issue in the world like the multi-drug-resistant bacteria, 85% of Iraqi war wounded have multi-drug-resistant bacteria, 70% of Syrian war wounded have it…

So we say: this ecology, this bio-sphere that the conflicts create is even altered at the basic DNA of the bacteria. We have several theories about it; partly it’s the role of the heavy metals in modern ordnance, which can trigger mutation in these bacteria that makes them resistant to antibiotics. So your bio-sphere, your bubble, your ecological bubble in which you live in, is permanently changed. And it doesn’t disappear the day the bombs disappear. It has to be dismantled, and in order to dismantle it you have to understand the dynamics of the ecology of war. That’s why our program was set up at the university, which had basically been the major tertiary teaching center during the civil war and the 1982 Israeli invasion. And then as the war in Iraq and Syria developed, we started to get patients from these countries and treat them here. We found out that we have to understand the dynamics of conflict medicine and to understand the ecology of war; how the physical, biological, psychological and social manifestations of war wounding happen, and how this ecology of war is created; everything from bacteria to the way water and the water cycle changes, to the toxic reminisce of war, to how people’s body reacts… Many of my Iraqi patients that I see have multiple members of their families injured.

AV: Is the AUB Medical Center now the pioneer in this research: the ecology of war?

GA-S: Yes, because of the legacy of the civil war… of regional wars.

AV: Nothing less than a regional perpetual conflict…

GA-S: Perpetual conflict, yes; first homegrown, and then regional. We are the referral center for the Iraqi Ministry of Health, referral center for the Iraqi Ministry of Interior, so we act as a regional center, and the aim of our program is to dedicate more time and space and energy to the understanding of how this ecology of war comes about.

AV: In my writing and in my films, I often draw the parallel between the war and extreme poverty. I have been working in some of the worst slums on Earth, those in Africa, Central America and Caribbean, South Asia, the Philippines and elsewhere. I concluded that many societies that are in theory living in peace are in reality living in prolonged or even perpetual wars. Extreme misery is a form of war, although there is no ‘declaration of war’, and there is no defined frontline. I covered both countless wars and countless places of extreme misery, and the parallel, especially the physical, psychological and social impact on human beings, appears to be striking. Would you agree, based on your research? Do you see extreme misery as a type of war?

GA-S: Absolutely. Yes. At the core of it is the ‘dehumanization’ of people. Extreme poverty is a form of violence. The more extreme this poverty becomes, the closer it comes to the physical nature of violence. War is the accelerated degradation of people’s life to reaching that extreme poverty. But that extreme poverty can be reached by a more gradual process. War only gets them there faster.

AV: A perpetual state of extreme poverty is in a way similar to a perpetual state of conflict, of a war.

GA-S: Definitely. And it is a war mainly against those who are forced to live in these circumstances. It’s the war against the poor and the South. It’s the war against the poor in the inner-cities of the West.

AV: When you are defining the ecology of war, are you also taking what we are now discussing into consideration? Are you researching the impact of extreme poverty on human bodies and human lives? In this region, extreme poverty can often be found in the enormous refugee camps, while in other parts of the world it dwells in countless slums.

GA-S: This extreme poverty is part of the ecology that we are discussing. One of the constituents of the ecology is when you take a wounded body and you place it in a harsh physical environment and you see how this body is re-wounded and re-wounded again, and this harsh environment becomes a continuation of that battleground, because what you see is a process of re-wounding. Not because you are still in the frontline somewhere in Syria, but because your kids are now living in a tent with 8 other people and they are in danger of becoming the victims of the epidemic of child burns that we now have in the refugee camps, because of poor and unsafe housing.

Let’s look at it from a different angle: what constitutes a war wound, or a conflict-related injury? Your most basic conflict-related injury is a gunshot wound and a blast injury from shrapnel. But what happens when you take that wounded body and throw it into a tent? What are the complications for this wounded body living in a harsh environment; does this constitute a war-related injury? When you impoverish the population to the point that you have children suffering from the kind of injuries that we know are the results of poor and unsafe housing, is that a conflict-related injury? Or you have children now who have work-related injuries, because they have to go and become the main breadwinners for the home, working as car mechanics or porters or whatever. Or do you also consider a fact that if you come from a country where a given disease used to be treatable there, but due to the destruction of a health system, that ailment is not treatable anymore, because the hospitals are gone or because doctors had to leave, does that constitute a conflict-related injury? So, we have to look at the entire ecology: beyond a bullet and shrapnel – things that get headlines in the first 20 seconds.

AV: Your research seems to be relevant to most parts of the world.

GA-S: Absolutely. Because we know that these humanitarian crises only exist in the imagination of the media and the UN agencies. There are no crises.

AV: It is perpetual state, again.

GA-S: Exactly, it is perpetual. It does not stop. It is there all the time. Therefore there is no concept of ‘temporality of crises’, one thing we are arguing against. There is no referee who blows the whistle at the end of the crises. When the cameras go off, the media and then the world, decides that the crises are over. But you know that people in Laos, for instance, still have one of the highest amputation rates in the world.

AV: I know. I worked there in the Plain of Jars, which is an enormous minefield even to this day.

GA-S: Or Vietnam, with the greatest child facial deformities in the world as a result of Agent Orange.

AV: You worked in these countries.

GA-S: Yes.

AV: Me too; and I used to live in Vietnam. That entire region is still suffering from what used to be known as the “Secret War”. In Laos, the poverty is so rampant that people are forced to sell unexploded US bombs for scrap. They periodically explode. In Cambodia, even between Seam Reap and the Thai border, there are villages where people are still dying or losing limbs.

GA-S: Now many things depend on how we define them. It is often a game of words.

AV: India is a war zone, from Kashmir to the Northeast, Bihar and slums of Mumbai.

GA-S: If you take the crudest way of measuring conflict, which is the number of people killed by weapons, Guatemala and Salvador have now more people slaughtered than they had during the war. But because the nature in which violence is exhibited changed, because it doesn’t carry a political tag now, it is not discussed. But actually, it is by the same people against the same people.

AV: I wrote about and filmed in Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua, on several occasions. The extreme violence there is a direct result of the conflict implanted, triggered by the West, particularly by the United States. The same could be said about such places like Jamaica, Dominican Republic and Haiti. It has led to almost absolute social collapse.

GA-S: Yes, in Jamaica, the CIA played a great role in the 70’s.

AV: In that part of the world we are not talking just about poverty…

GA-S: No, no. We are talking AK-47’s!

AV: Exactly. Once I filmed in San Salvador, in a gangland… A friend, a local liberation theology priest kindly drove me around. We made two loops. The first loop was fine. On the second one they opened fire at our Land Cruiser, with some heavy stuff. The side of our car was full of bullet holes, and they blew two tires. We got away just on our rims. In the villages, maras simply come and plunder and rape. They take what they want. It is a war.

GA-S: ICRC, they train surgeons in these countries. So the ICRC introduced war surgery into the medical curriculum of the medical schools in Colombia and Honduras. Because effectively, these countries are in a war, so you have to train surgeons, so they know what to do when they receive 4-5 patients every day, with gunshot wounds.

AV: Let me tell you what I witnessed in Haiti, just to illustrate your point. Years ago I was working in Cité Soleil, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. They say it is the most dangerous ‘neighborhood’ or slum on Earth. The local wisdom goes: “you can enter, but you will never leave alive”. I went there with a truck, with two armed guards, but they were so scared that they just abandoned me there, with my big cameras and everything, standing in the middle of the road. I continued working; I had no choice. At one point I saw a long line in front of some walled compound. I went in. What I was suddenly facing was thoroughly shocking: several local people on some wooden tables, blood everywhere, and numerous US military medics and doctors performing surgeries under the open sky. It was hot, flies and dirt everywhere… A man told me his wife had a huge tumor. Without even checking what it was, the medics put her on a table, gave her “local” and began removing the stuff. After the surgery was over, a husband and wife walked slowly to a bus stop and went home. A couple of kilometers from there I found a well-equipped and clean US medical facility, but only for US troops and staff. I asked the doctors what they were really doing in Haiti and they were quiet open about it; they replied: “we are training for combat scenario… This is as close to a war that we can get.” They were experimenting on human beings, of course; learning how to operate during the combat…

GA-S: So, the distinction is only in definitions.

AV: As a surgeon who has worked all over the Middle East but also in many other parts of the world, how would you compare the conflict here to the conflicts in Asia, the Great Lakes of Africa and elsewhere?

GA-S: In the Middle East, you still have people remembering when they had hospitals. Iraqis who come to my clinic remember the 80’s. They know that life was different and could have been different. And they are health-literate. The other issue is that in 2014 alone, some 30,000 Iraqis were injured. The numbers are astounding. We don’t have a grasp of the numbers in Libya, the amount of ethnic cleansing and killing that is happening in Libya. In terms of numbers, they are profound, but in terms of the effect, we are at the beginning of the phase of de-medicalization. So it wasn’t that these medical systems did not develop. They are being de-developed. They are going backwards.

AV: Are you blaming Western imperialism for the situation?

GA-S: If you look at the sanctions and what they did to their health system, of course! If you look at Libya, of course! The idea that these states disintegrated is a falsehood. We know what the dynamics of the sanctions were in Iraq, and what happened in Iraq after 2003. We know what happened in Libya.

AV: Or in Afghanistan…

GA-S: The first thing that the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan or the Nicaraguan Contras were told to do was to attack the clinics. The Americans have always understood that you destroy the state by preventing it from providing these non-coercive powers that I spoke about.

AV: Do you see this part of the world as the most effected, most damaged?

GA-S: At this moment and time certainly. And the statistics show it. I think around 60% of those dying from wars are killed in this region…

AV: And how do you define this region geographically?

GA-S: From Afghanistan to Mauritania. And that includes the Algerian-Mali border. The Libyan border… The catastrophe of the division of Sudan, what’s happening in South Sudan, what’s happening in Somalia, Libya, Egypt, the Sinai Desert, Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, even Pakistan including people who are killed there by drones…

AV: But then we also have around 10 million people who have died in the Democratic Republic of Congo, since the 1995 Rwandan invasion…

GA-S: Now that is a little bit different. That is the ‘more advanced phase’: when you’ve completely taken away the state… In the Arab world Libya is the closest to that scenario. There the oil companies have taken over the country. The mining companies are occupying DRC. And they run the wars directly, rather than through the Western armies. You erode the state, completely, until it disappears and then the corporations, directly, as they did in the colonialist phase during the East Indian Company, and the Dutch companies, become the main players again.

AV: What is the goal of your research, the enormous project called the “Ecology of War”?

GA-S: One of the things that we insist on is this holistic approach. The compartmentalization is part of the censorship process. “You are a microbiologist then only look what is happening with the bacteria… You are an orthopedic surgeon, so you only have to look at the blast injuries, bombs, landmine injuries…” So that compartmentalization prevents bringing together people who are able to see the whole picture. Therefore we are insisting that this program also has social scientists, political scientists, anthropologists, microbiologists, surgeons… Otherwise we’d just see the small science. We are trying to put the sciences together to see the bigger picture. We try to put the pieces of puzzle together, and to see the bigger picture.

AV: And now you have a big conference. On the 15th of May…

GA-S: Now we have a big conference; basically the first congress that will look at all these aspects of conflict and health; from the surgical, to the reconstruction of damaged bodies, to the issues of medical resistance of bacteria, infectious diseases, to some absolutely basic issues. Like, before the war there were 30,000 kidney-failure patients in Yemen. Most dialysis patients are 2 weeks away from dying if they don’t get dialysis. So, there is a session looking at how you provide dialysis in the middle of these conflicts? What do you do, because dialysis services are so centralized? The movement of patients is not easy, and the sanctions… One topic will be ‘cancer and war’… So this conference will be as holistic as possible, of the relationship between the conflict and health.

We expect over 300 delegates, and we will have speakers from India, Yemen, Palestine, Syria, from the UK, we have people coming from the humanitarian sector, from ICRC, people who worked in Africa and the Middle East, we have people who worked in previous wars and are now working in current wars, so we have a mix of people from different fields.

AV: What is the ultimate goal of the program?

GA-S: We have to imagine the health of the region beyond the state. On the conceptual level, we need to try to figure out what is happening. We can already see certain patterns. One of them is the regionalization of healthcare. The fact that Libyans get treated in Tunisia, Iraqis and Syrians get treated in Beirut, Yemenis get treated in Jordan. So you already have the disintegration of these states and the migration of people to the regional centers. The state is no longer a major player, because the state was basically destroyed. We feel that this is a disease of the near future, medium future and long-term future. Therefore we have to understand it, in order to better treat it, we have to put mechanisms in place that this knowledge transfers into the medical education system, which will produce medical professionals who are better equipped to deal with this health system. We have to make sure that people are aware of many nuances of the conflict, beyond the shrapnel and beyond the bullet. The more research we put into this area of the conflict and health, the more transferable technologies we develop – the better healthcare we’d be allowed to deliver in these situations, the better training our students and graduates would receive, and better work they will perform in this region for the next 10 or 15 years.

AV: And hopefully more lives would be saved…

• All photos by Andre Vltchek