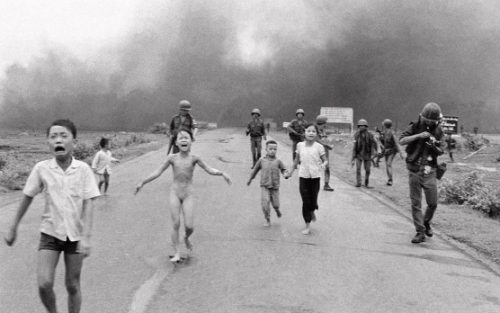

The row about Facebook censoring the iconic photograph of a naked Vietnamese girl, Kim Phúc, fleeing a US napalm attack has led to justified outrage. But it is also helping to solidify deeply misguided assumptions about the supposed differences between “new” and “old” media.

That view is illustrated in this article today by Norwegian prime minister Erna Solberg. She states:

Media consumption today is increasingly digitized, but even more so it is curated. News and social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Flipboard have overtaken traditional news outlets as our primary sources of information, of news, of connection to the world around us. …

Already, Facebook and other media outlets’ algorithms narrow the range of content one sees based on past preferences and interests. This limits the kind of stories one sees, and in turn restricts access to a holistic outlook for the user. We run the risk of creating parallel societies in which some people are not aware of the real issues facing the world, and this is only exacerbated by such editorial oversight. …

It would be tragic for history, for the truth, to be told in the version that comes from any one corporation’s mouthpiece. This is why I believe it is imperative that such outlets take their responsibility seriously, while exercising such great influence over their users’ access to information.

It is true that Facebook and other new media platforms increasingly control how we see and understand the world. But there is nothing new about this. Such control existed long before anyone had heard of Facebook. Corporations were deciding what access we have to information, acting as gatekeepers, decades before the internet was invented. And before them, the church and its priests controlled what was considered “knowledge” in western societies.

Solberg is also wrong to think that a loss of access to information may come about because people like Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg have not properly thought through the way their platforms operate.

If there is one aphorism, it is this: Power seeks to perpetuate itself. In other words, the powerful invest their efforts in ensuring they hold on to power (and the wealth that comes with it). If knowledge is power, then the powerful must make sure they alone control the flow of information.

Once Rupert Murdoch performed this role. Now, increasingly, Zuckerberg and Google do. To think they were ever likely to be more benevolent than the corporations of old is to subscribe to magical thinking.

In fact, a more realistic assessment is that we are experiencing a brief and heady informational renaissance during the transition between the old and new medias. For a short period, as power shifts from one set of media corporations to another, a small window of information anarchy has reigned. We on the left have tried to take advantage of this as best we can.

The results are already visible: increasing political polarisation of our societies as small groups of the public start to gain access to different sources of information – writers, thinkers and journalists who could never have reached them in the pre-internet era.

That additional information has alienated them from the traditional centres of power, including the old media. With a new understanding of our societies’ histories and their disruptive role in the world, these groups have rightly become deeply distrustful of western elites.

But if history offers any clues, that freedom is not likely to continue – unless we fight very hard for it. The powerful see what damage a slight liberalisation of the market in information has done already. It has created Jeremy Corbyn, Bernie Sanders, Podemos and Syriza. It has fuelled a wider disenchantment that is reflected in the breakdown of the status quo. Its diverse outcomes (some good, some bad) include the Arab Spring; the emergence first of the Occupy movement and now of Black Lives Matter; the rise of Donald Trump; the Brexit vote, and growing demands for Scottish independence; the BDS campaign demanding justice for the Palestinians, and greater exposure to home-grown terrorism.

This political instability offers Disaster Capitalism-style opportunities for the powerful. But they will not willingly allow controlled instability to degenerate into political anarchy, let alone revolutionary change. Which is why the new media will increasingly re-assert a corporate grip on information, corralling dissidents back into their knowledge ghettoes – those “parallel societies” Solberg speaks of.

That is the task before Zuckerberg, Google and others. In the coming years they will master it, whether we give it a Facebook thumbs-up or not.