Cultural pessimists don’t see much they like at the Paris climate talks. Skepticism at times like these is nearly always justified. At the same time, it may be that Paris was a minute improvement — on some issues — upon the previous gatherings of elected officials, diplomats, corporate hacks, activists, celebrities, and media that constitute these annual circuses. And it’s likely that the angry and energized climate justice movement is primed to pressure the big polluters like never before. No, the glass is not half full. Delegates will not agree to emissions reductions necessary to meet even their own inadequate target of 2 degrees C increase in global temperature. It’s thus possible to see the draft treaty as a step backward.

Naturally an adequate treaty would’ve been better than what we’ll end up with. The glass isn’t half empty either. Paris is not the last Conference of Parties (COP; there’s one every year). And it’s not realistic under the present circumstances to expect two hundred countries with deeply conflicting interests and grossly unequal power to hammer out a joint agreement on humanity’s future. Left to their own devices, leaders of the major powers (both North and South) would for a variety of reasons leave the planet on an accelerating vector towards climate catastrophe. But that’s the point: they must be hounded and harangued to do what’s needed, to improve on Paris, immediately upon their return home, and for the foreseeable future. The political climate must change before we can stop warming the planetary climate.

The Issues Outstanding and What to Do About Them

There’s no doubt the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions — UN-speak for national emissions reduction targets — committed to in advance of the conference by participating countries (virtually every nation-state on the planet) are not up to the job. This is so even if countries stick to them, which they don’t have to because they are voluntary. And this is so even if the goal is to keep global temperature increase to no more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, let alone the safer 1.5 degrees C pushed by the climate justice movement whose advocacy now has the UN climate cavalcade seriously considering the lower goal.

Fans of legally binding reduction targets, with real penalties for failure to meet them (any thinking person), are naturally disappointed. For the United States to commit to binding targets of this sort would make any agreement a “treaty” thus requiring ratification by the Senate where the text, any text, would be dead on arrival. Yet these targets are better than no replacement for the Kyoto Protocol, slated to sunset in 2020 at which point the agreement negotiated in Paris kicks in. Activists must work to improve the political prospects for binding and tougher targets at a future COP — the Paris cuts are not etched in stone. National climate justice movements must also force their own governments to treat the voluntary targets as binding in the meantime, and advocate for upwardly flexible targets actually in synch with ever gloomier climate science.

Paris climate delegates use the term “differentiation” when discussing a core principle of climate justice: the responsibility of the nations that caused the problem to solve it. Obama’s self-proclaimed success in Copenhagen was to get key world leaders to again proclaim the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities.” Translation: we’re all in this together, but some of us will have to do more than others. It was the “we’re all in this together” part that was Obama’s aim. As for the “some do more:” rich countries’ fear that they will justifiably be saddled with deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions while (most of) the Global South justifiably emits more or less freely.

As always, the devil resides in the fine print: who gets to emit how much for how long? To the surprise of no one, nearly every Republican in the US Congress is simply unwilling to acknowledge the country’s climate debt to the rest of the world (especially poor and thus particularly vulnerable states); they oppose any agreement, but especially climate just versions. They propagate patently dishonest arguments that resonate with ignorant voters. That China recently surpassed the US as the planet’s number one emitter of carbon bolsters their weak and self-defeating case. Obama’s sketchy deal with Chinese President Xi in advance of Paris did little to undermine resistance to climate justice among elected American officials. The task of (inter)national climate justice movements is to get their own (sub)governments and the world as a whole to make as rapid a transition to completely clean energy systems. There’s impressive and heartening climate justice work being done at city, county and state levels. Provinces and municipalities are vitally important especially when central governments are unable to move as in the US.

Hundreds of environmentalists arrange their bodies to form a message of hope and peace in front of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France, December 6, 2015, as the World Climate Change Conference 2015 (COP21) continues at Le Bourget near the French capital. REUTERS/Benoit Tessier – RTX1XF6Y

The stupidity of opposition to a just transition away from dirty energy is more evident every day. Jobs and profits are steadily disappearing from fossil fuel and mineral production and heading to conservation, efficiency, and renewables. Numerous convincing studies of the economic, ecosystem, and human health benefits of a full transition to a fully clean energy economy have appeared. Economists agree it’s far cheaper to take action now than later, that the longer we wait the greater the costs of all sorts, and that it’s ultimately cheaper, smarter and more humane to prevent “natural disasters” than it is to respond to and rebuild after them.

Secretary of State John Kerry announced in Paris on December 9 that the US would double its contribution to the Green Climate Fund, the UN vehicle for financial assistance to developing countries’ for mitigation and adaptation projects from $430 million to $860 million by 2020. Kerry’s pledge may be little more than carbon dioxide: (1) Obama will be gone in January 2017, and thus unable to deliver; (2) the extra money counts toward Hillary Clinton’s 2009 promise in Copenhagen that the Global North would make available $100 billion (a mix of public and private money) per year by 2020 (Kerry’s pledge is, in other words, but accelerated spending of already promised monies); (3) India —third largest emitter of carbon pollution — demands greater public aid from rich countries rather than rely on private investors; (4) Republicans in Congress are already fighting disbursement of the first installment of an earlier Obama commitment; and (5) the increased pledge is meant to forestall poor country solidarity in Paris on “loss and damage” (about which more below).

Alongside US promises of more money to help poor countries cope with problems caused by the rich countries, comes a public-private energy R&D partnership engineered by philanthrocapitalist Bill Gates. Over the past year, Gates talked French President Francoise Hollande, Obama, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and some of the world’s richest man’s richest pals into putting money into the new kitty. Were the “Breakthrough Energy Coalition” investing in more efficient solar cells or improved geothermal systems, observers might suppress their gag reflexes at the capacity of gazillionaires to steer public agendas. But as Linda Pentz Gunter suggests, the research investment club appears little more than a better-funded hunt for the unicorn that is safe nuclear power.

Gates’ (and everyone else’s) money would be better spent ending energy poverty with existing clean technology like offshore wind farms, or by compensating poor countries for present and growing “loss and damage” from climate change. The concept of loss and damage is tails to the heads of differentiation on the climate justice coin. A life and death concern of small-island states since the outset of the UN climate convention process twenty years ago, they managed to partially overcome the concept’s taboo status with rich country delegations at COP16 in Cancun in 2010. Loss and damage remains an intentionally fuzzy concept for the Framework Convention — an official report aiming to clarify the notion is finally due at COP22 next year.

It’s less fuzzy when substituting the words liability and compensation for loss and damage. Funds for liability and compensation should not be confused with contributions of the sort announced by Kerry and Gates. The Green Climate Fund aims to transfer funds from rich to poor countries for mitigation and adaptation projects designed to avoid loss and damage. Liability and compensation is responsibility and reparations for the untold destruction that will not be avoided even after implementation of strong mitigation and adaptation measures. This is why it’s been unthinkable until recently for Global North climate diplomats. And this is why it’s essential for climate justice activists in rich countries to add loss and damage funds to their lists of demands. In the United States, it means directly confronting cruel and xenophobic Republican legislators about global loss and damage from climate instability even while the Republicans work to undermine domestic tort law.

Sticking points over the final text of the Paris agreement include how often to review progress towards national emissions reduction targets, whether progress reports should be binding, who should perform the reviews, and whether the monitoring process should be transparent. Climate justice advocates generally favor frequent, binding, independently verified, transparent reviews. The United States and the European Union already perform independent and open greenhouse gas inventories. The US and EU also believe that they can meet their voluntary targets even if they’re modestly ramped up following periodic, mandatory reviews. China, India, Brazil and South Africa are decidedly less sanguine about the proposed review regime.

The Europeans and Americans thus find themselves in an unlikely coalition with 79 Asian, African and Latin American countries — constituting a majority of countries present in Paris — arrayed against most of the BRICS. Some crafty and secret diplomacy led to a limited alliance of history’s biggest polluters with climate change’s biggest losers against countries looking to replace the Western bloc as economic hegemons.

The Necessity for Mass Action in and After Paris

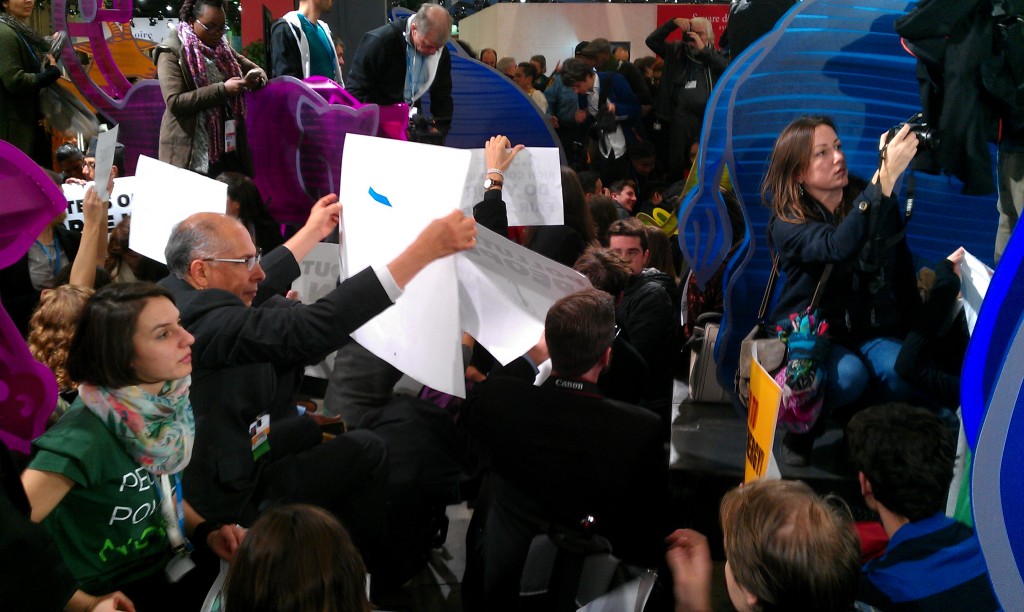

Activists at an unauthorized protest on December 9 inside the climate negotiations in Paris. Photo: Peter Teffer.

The Hollande government used the pretext of the Paris terror attacks of November 13 to ban mass demonstrations planned for the climate talks. On November 28-29, hundreds of thousands of us took part in marches, rallies and other events around the world to send a strong message on the eve of the climate summit, and to show that we were deterred neither by terrorists nor by attempts to silence us. On Wednesday of this week, hundreds of campaigners stormed the Paris COP, marching down the main hallway, to protest the draft agreement and demand climate justice. Voices neglected by the official negotiators — especially women and indigenous people —were loud and clear. GAIA took over a municipal conference trying to rebuild a waste incinerator in Paris. Chances are there will be more such productive interventions before the talks wrap up; an agreement was supposed to be sealed by Friday but negotiations may extend into the weekend.

Again, climate justice activists are sure to be disappointed by the final text. It will not go far enough fast enough. It will ignore vital concerns and downplay essential principles. But whatever emerges from Paris ought to be seen as but one small, imperfect step towards climate justice. Giant leaps are necessary, and it will take the redoubled efforts of vibrant climate justice groups to enable them. Despite disappointment, activists gathering alongside the COPs and similar events — both onsite and remotely — helps build the movements. Groups and organizers improve communications within and across borders, share strategies, tactics and experiences, advance new concepts, enhance movement culture, and plan next steps.

The next steps in the United States take the form of any number of exciting and valuable campaigns. Fossil fuel divestment efforts are increasingly successful and significant. There’s resistance to pipelines and other new fossil fuel infrastructure across the country. The anti-fracking movement has not let up. The “keep it in the ground” folks recently caused the Obama administration to cancel a planned oil lease. Anti-nuclear activism remains as central as ever. Peace Action calls for redirection of ten percent of global military expenditures to climate protection. Zero waste groups press for alternatives to trashing the planet. The prospects for climate justice advocates to more firmly join forces with other movements, especially labor, peace, women’s, and indigenous rights are better than ever.

Whatever problems people care about, climate pollution is sure to make them worse. Connect your issue to the climate justice caravan. It’ll be the ride of your life.