“Since my life as a prisoner has begun, I have heard of some white men who said they owned my land and my home. I don’t believe they do. I have never given any consent to such ownership. The land belongs to my people and to our children.”1

“We were taught that God’s laws are about how we treat each other and the land. The white man doesn’t obey God’s laws. They take the land that belongs to us, the land that God gave us.”2

– Chief Geronimo.

“The Great Spirit gave this great island to his red children. He placed the whites on the other side of the big water. They were not contented with their own, but came to take ours from us. They have driven us from the sea to the lakes — we can go no farther.”3

– Chief Tecumseh.

“The white man has made many promises to us, and they have kept but one. They promised to take our land, and they have taken it.”4

– Chief Red Cloud.

“My lands are where my dead lie buried.”5

– Chief Crazy Horse.

To sit with Elder Ttesalaq—Tom Sampson—of the Tsartlip First Nation is to be granted an audience with living history. His words are not merely recollections; they are the continuous, unbroken thread of a nation’s memory, stretching back to a time before the word “Canada” was ever uttered on these shores. To understand his testimony is to undertake a fundamental re-examination of the story Canada tells about itself. It reveals a narrative not of benevolent nation-building, but of a guest who moved into the house, claimed the deed, and has been trying to evict the original owners ever since. This truth stands in stark contrast to the official discourse of “Truth and Reconciliation,” which across the vast apparatus of the Canadian state and its media echo chambers, reveals a sophisticated architecture of avoidance. This architecture is designed to manage the symptoms of settler-colonialism—the pain, the cultural loss—while carefully protecting its root cause: the systematic robbery of the land itself.

The Original Welcome: A Host Becomes a “Refugee” in His Own Land

Elder Ttesalaq begins not with accusation, but with a profound act of empathy. “We welcomed the first refugees that came here in 1492,” he states, framing a history of Indigenous generosity that provided food, medicine, and land. This was not a transaction but a foundational principle of his civilization.

The great, painful irony he identifies is that this act of welcome was perverted into a logic of dispossession. “We were put under the Ministry of Immigration in the early days,” he notes with a wry, painful clarity. “So we were considered immigrants in our own country.” This single, bureaucratic act encapsulates the entire colonial project: to render the host a stranger, the native an alien. The Canadian state, from its very inception in the Indian Act and the reserve system, has been an engine of identity reassignment, systematically working to erase the original political identities of the peoples it encountered.

The Douglas Treaty: A “Nation-to-Nation” Agreement Betrayed

At the core of Elder Ttesalaq’s testimony is the Douglas Treaty of 1852. For him, this is the legal and moral cornerstone that the Canadian state has spent over a century undermining. He is meticulous in his historical framing: this was not a treaty with Canada. Canada did not exist. It was a treaty between the Saanich Nations and the British Crown, represented by Governor James Douglas.

The treaty’s promise was simple and profound: the Saanich people would be allowed to hunt and fish “as formerly,” as if they were the “sole occupants of the land.” In return, they granted the Crown permission to settle. “We gave him the right to come here,” Elder Ttesalaq corrects the colonial narrative. “He didn’t give us any rights.” This distinction is critical. Sovereignty was not ceded; access was granted.

The betrayal began with Confederation in 1867. The Crown transferred its authority to the new federal government of Canada without the consent of the treaty signatories. “Our treaty’s been breached straight since 1867 right to the present day,” he states. The creation of Indian reserves was the first and most catastrophic breach. The Indian Act then became the primary tool of control, creating a system of “delegated authority” where Band Councils were transformed into “Crown corporations,” effectively making them administrators of their own oppression. “The colonizer is now our own people,” he laments. “We have become the colonizer.”

The Long War in the Courts: Rights Recognized but Never Respected

A significant portion of Elder Ttesalaq’s narrative is dedicated to the relentless legal battle his people have been forced to wage. He speaks not with the zeal of a victor, but with the weary frustration of a man who has won the argument a dozen times over, only to have his opponent pretend the debate never happened.

He recounts how the Supreme Court of Canada has consistently ruled in favour of Indigenous rights. He references Section 35 of the Constitution, which affirms existing Aboriginal and treaty rights, and which a federal minister once called a “full box.” He cites the 1997 Delgamuukw decision, where the Court acknowledged that Aboriginal title had never been extinguished. “They knew that as late as 1997, they knew that they never had extinguished Aboriginal title and Aboriginal rights. And yet they continue to pretend that they owned everything.”

The tragedy, in his view, is the intransigence of the bureaucracy. “The bureaucrats, British Columbia, Ottawa, the Department of Indian Affairs, they don’t seem to understand that the law has changed in this country and they don’t want to change it.” He describes a Canadian state that functions as a schizophrenic entity: its judicial branch affirming rights, while its executive and legislative branches spend hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars to fight those same rights. It is a state at war with its own legal foundation.

The Bureaucratic Mask: Polishing the Machinery of Dispossession

This judicial truth is met with what Elder Ttesalaq identifies as a wall of bureaucratic resistance—a pattern that reveals itself with stark clarity across the state’s own institutions. The Department of National Defence (DND), in its “Towards Truth and Reconciliation” report, speaks of “harm” and “assimilation” but is utterly silent on the historical and ongoing use of military force to dispossess Indigenous peoples of their lands. For the DND to discuss reconciliation without confessing its role as the ultimate guarantor of the state’s territorial claims is the height of irony.

This sleight-of-hand finds its most sophisticated expression in the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada (IAAC). Its “Reconciliation Framework” is a masterpiece of procedural liberalism: it outlines how to consult Indigenous peoples on new resource projects, but never once questions the underlying authority of the Canadian state to grant permission for the extraction of wealth from unceded land. The entire process is designed to make Indigenous communities stakeholders in their own dispossession, rather than sovereign nations with the power to grant or refuse consent.

The Symbolic Veil and the Complicit Echo

At the highest symbolic levels, the avoidance becomes a form of political theater. The Governor General, the representative of the very Crown that asserted sovereignty over Indigenous nations, frames reconciliation as a matter of “listening” and “dialogue.” This transforms a fundamental political struggle over jurisdiction and territory into a therapeutic process of interpersonal understanding.

The most telling performances come on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. The Prime Minister’s statements and the accompanying Canadian Heritage pages are saturated with the language of “reflection,” “honour,” and “painful legacy.” They speak of “colonial policies” in the abstract but will not utter the words “settler colonialism.” They mourn the loss of “ways of life” but will not admit that the goal was to destroy the political and economic bases of those ways of life to clear the land for settlement and resource extraction. This is reconciliation as a public ritual of mourning for cultural loss, deliberately severed from the material reality of property and power.

This state-driven narrative is amplified by the complicit machinery of mainstream media. Outlets like the Globe and Mail often provide “explainer” journalism that focuses on the what and the when of reconciliation, while omitting the why. They personalize the story through powerful, heart-wrenching accounts like that of Phyllis Webstad’s orange shirt, yet in doing so, they often individualize a systemic crime, directing public empathy toward a single instance of a taken shirt, subtly diverting attention from the larger, more politically explosive story of taken continents.

Even the state-funded Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) finds itself structurally bound within this architecture of avoidance. For instance, a CBC article headlined “As 5th National Day for Truth and Reconciliation arrives, many say little has changed,” quotes Indigenous leaders who state plainly that the government’s “piecemeal approach” prioritizes “performance over progress” and fails to act on “land dispossession and resource sharing.” Yet, as a state-funded institution, the CBC’s mandate is inextricably linked to the very state it is critiquing. It can report on the government’s failure to live up to its own promises, but it cannot consistently and fundamentally question the legitimacy or foundational claims of the colonial state that provide its mandate and foundation. It is a “critic” from within the palace walls, its voice constrained by the very architecture it describes, ultimately reinforcing the boundaries of a conversation that must never challenge the state’s ultimate authority over the land.

The Unmasking: The RCMP and the Guardian of the Theft

The most potent example of this architectural avoidance is found in the so-called Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Their pages on “Indigenous Policing” and how they “Advance Reconciliation” are not merely omissions; they are active, breathtaking acts of historical whitewashing. The RCMP was not created to be a neutral police service. It was established as a paramilitary force with an explicit colonial mandate: to assert Canadian sovereignty over Indigenous lands and to suppress resistance.

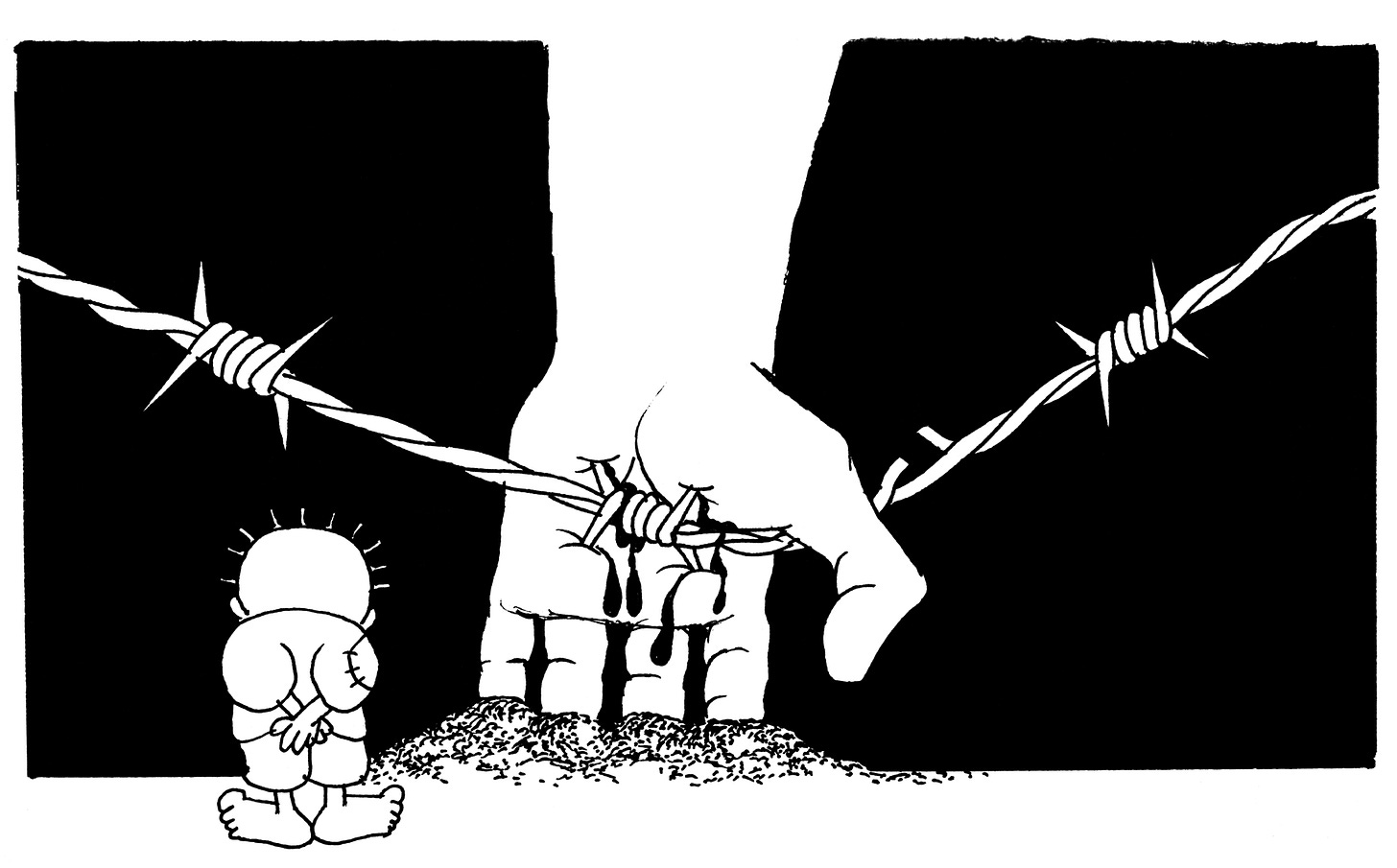

For the RCMP to speak of “building trust” is the ultimate hypocrisy, because its historical role was to systematically break the will of Indigenous nations. This institution was the primary enforcement arm for the residential school system; RCMP agents were the ones who forcibly kidnapped children from their families at gunpoint. They also enforced the illegal pass system and suppressed the Métis Resistance. Today, their “reconciliation” framework focuses on “cultural competency.” This is a safe admission that allows them to acknowledge a flaw in their culture without confronting their foundational settler-colonial purpose. Their modern, militarized raids on Wet’suwet’en land to protect pipeline construction are not an aberration; they are the continuation of their original purpose: to protect the state’s claim to the stolen land and the resources beneath it.

Against this backdrop of state-sponsored ambiguity, the clarity of the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) acts as a powerful unmasking of the state’s true motives. Its statement does what other bodies refuse to do, naming the residential school system as “a key component of a deliberate, settler-colonial policy of assimilation designed to eliminate First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples as distinct peoples and to gain access to their lands and resources.” By correctly identifying this as a “land-based project,” the CHRC lays the motive bare: the entire colonial endeavor was, and is, a project of land robbery.

This truth is not new. It is meticulously documented in the foundational work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The TRC’s Calls to Action are a blueprint for dismantling the legal and philosophical underpinnings of the colonial state. Call to Action 46, which demands the repudiation of the “Doctrine of Discovery” and terra nullius, is a direct assault on the legal justification for centuries of land theft. The failure of the state to fully implement these calls is the evidence of its bad faith.

The Land and the Cost: Reconciliation Versus Reality

For Elder Ttesalaq, these abstract legal and bureaucratic battles manifest in the very concrete devastation of his people’s land and waters. The fight against the Kinder Morgan pipeline is the defence of a way of life guaranteed by treaty. “The issue is that it’s going through our territory, our land, and our resources are at risk.”

He speaks with the authority of a scientist who has inherited millennia of data. He recalls elders in 1947 noting the waters were warming and the fish were moving—early warnings of climate change that were ignored because the bearers lacked “a degree and diploma.” Now, the evidence is everywhere: the dying salmon, the vanished herring, the polluted air. “My world has already come to an end,” he says, a statement of devastating finality. “All my food, all our food from the ocean that we needed, all the birds that used to be in the sky are gone.”

This environmental cataclysm is inextricably linked to the unfinished business of the treaty. The Canadian state and its corporate partners see land as a “commercial commodity,” while for the Saanich, it is a relative, named and known, part of a family. True reconciliation, therefore, is impossible without reconciling with the land itself. “It’s not just reconciliation with Indigenous people; it’s reconciliation with the land and reconciliation with the ocean and reconciling the air that we once breathe.”

The Unfinished Struggle

Ultimately, Elder Ttesalaq presents a deeply sobering critique. For him, the truth is known and has been affirmed by the courts and its own commissions; the failure is in the reconciliation, which remains a hollow performance so long as the fundamental issues of land and sovereignty remain unaddressed. He points to the ongoing, visceral racism and police violence as proof of the state’s insincerity. How can there be reconciliation, he asks, when one side still holds the power of life and death over the other? When the state’s laws, like the Indian Act, continue to impose what he unequivocally names an “apartheid system”?

Elder Ttesalaq’s testimony is not a plea, but a declaration. It is a map of a parallel Canada, one where the Douglas Treaty is the supreme law and where the original relationship of host and guest has yet to be restored. The path forward is not one of assimilation, but of recognition. “We’re not going to be French, we’re not going to be English,” he asserts. The goal is an “equal right,” where Indigenous nations can exercise their inherent sovereignty.

The Canadian state stands at a crossroads. It can continue to spend billions fighting a truth it has already lost, perpetuating a conflict that poisons the land and its people. Or, it can finally “come to terms” with the original nation-to-settlers agreement and dismantle the apartheid system it built. Until it has the courage to face this truth and relinquish its grip on the stolen prize, the promise of reconciliation will remain, like the treaty itself, an unkept promise, and the unfinished struggle of this land will continue to demand a reckoning.

ENDNOTES:

1 Chief Geronimo: In the Days of Victorio: Recollections of a Warm Springs Apache by Eve Ball, as told to her by James Kaywaykla.

2 Chief Geronimo: His Own Story, as told to S.M. Barrett.

3 Chief Tecumseh: The Life of Tecumseh and His Brother the Prophet by Benjamin Drake.

4 “Chief Red Cloud: A speech given at a council at Fort Laramie,” as recorded in the New York Times, May 7, 1870.

5 “Chief Crazy Horse: A statement made to Lieutenant William Philo Clark,” as recorded by He Dog.