Before the Bush administration goes, its many assaults to basic decency will include putting cloned farm animals on the planet. On the 15th of this month, the Food and Drug Administration made the United States the first country to approve animal cloning for the retail food industry.

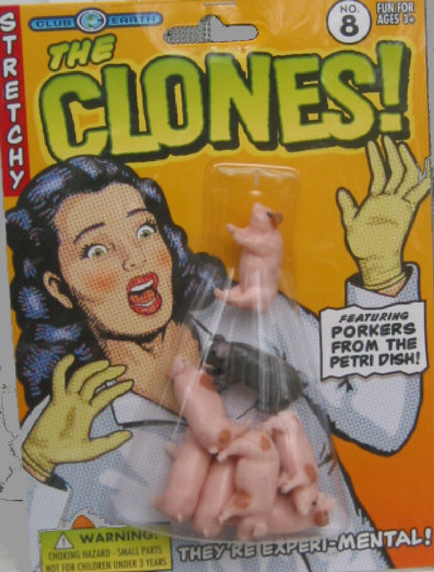

Toy clones manufactured for children aged three and up, sold by Club Earth, a Rhode Island company. Photo by Lee Hall, who thanks Lisa M. Stanley for finding them.

The European Union is poised to follow along, clearing the way for international trade to accept clone-derived flesh and dairy products. The European Food Safety Authority has announced, “[A]ssuming that unhealthy clones are removed from entering the food chain, it is very unlikely that any difference exists in terms of food safety between food products originating from clones and their progeny compared with those derived from conventionally bred animals.”

What are these people thinking?

The FDA is pushing this plan at the behest of a few heads of companies who promise replicas of animals most likely to be transformed into prime beef and bacon, or prolific milk producers. The dairy industry, which is already so prolific that taxpayers must buy surplus milk, has not championed the idea. Expecting to benefit most from the approval are the actual clonemakers, like Texas-based ViaGen, Inc., which is backed by billionaire investor John Sperling.

Privately held ViaGen, started in 2001 and backed by billionaire investor John Sperling, hasn’t had the money troubles that have plagued rivals. The octogenarian Sperling founded the for-profit University of Phoenix in 1976, now part of the publicly traded Apollo Group. For almost 10 years, he has doled out money to back a number of projects, including a failed attempt to clone his dog Missy. Her picture now hangs in ViaGen’s office as inspiration. ViaGen’s website boasts of cloning the “legendary barrel racing champion Scamper” and shows “calves cloned from Kung Fu, the mother of many famous rodeo bulls.”

The Federation of Animal Science Societies has run a PR campaign for cloning. “The entertainment industry has used the word ‘clone’ in a negative context,” said Jerry Baker, the group’s chief executive. “That’s a hard one for us to overcome, but we have to continue to try.”

While nonhuman cloning has always been legal in the United States, a voluntary moratorium on the sales of clones’ milk and flesh has applied since 2001. A 2002 National Academy of Science report concluded that products derived from cloned animals do not “present a food safety concern,” and the FDA gave a tentative approval in 2003, but retreated after its advisory panel reported a lack of consensus.

But they’ve gone and done it now.

“Meat and milk from cattle, swine and goat clones is as safe to eat as the food we eat every day,” said Stephen Sundlof, the FDA’s head vet. Sounds like the vet from Hell. Clones die from respiratory, digestive, circulatory, nervous, muscular, skeletal and placental abnormalities. Cows die trying to bear grotesquely oversized calves. Piglets have been born without anuses and tails — a fatal condition. Far more cloning attempts fail than succeed.

So there we have it: Cows, pigs and goats, our species has spoken. You’re cleared for cloning.

Rock Stars of the Barnyard

This month has seen the human cloning debate revived in light of some startling events. Not only did the CEO of a small California biotech company put DNA from his own skin into a human egg to begin the process of making human clones

The United Nations’ Declaration on Human Cloning asks member states to “prohibit all forms of human cloning inasmuch as they are incompatible with human dignity and the protection of human life.” The dignity of nonhuman life attracts far less notice. A widely cited series of polls carried out by the Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology reported that over 60 percent of U.S. consumers are uncomfortable with animal cloning, but only about 10 percent of those respondents saw the animals at the core of their discomfort.

The cloning companies dismiss their concerns with the most cavalier statements. “Cloning enhances animal wellbeing,” declares the Biotechnology Industry Organization; and Clonesafety.org, sponsored by cloning firms Cyagra, stART Licensing, and ViaGen, assures us: “In fact, clones are the ‘rock stars’ of the barnyard, and therefore are treated like royalty.”

With a strained informality, proponents speak of clones as later-born twins of their originals, and of cloning as merely expanding the reproduction technology available to farmers since the 1950s.

Early last year, when a calf of a cloned cow was born in Britain, Simon Gee of the breeder’s group Holstein UK said the calf, Dundee Paradise, resulted from “conventional breeding technology” and was “born as the majority of the 220,000 animals that we register in the U.K. every year are born — as a result of artificial insemination.”

But the majority of those registered animals don’t come from embryos imported from U.S. labs, as Dundee Paradise did.

Still, if domination and control is at the core of cloning, then the basis of the problem is the public’s willingness to consume animals in the first place. If animals can be bred, born and viewed as food items, virtually any manipulation will, sooner or later, be allowed. At a fundamental level, that’s why statements from the Organic Consumers Association, or from any other well-meaning group that declines to question the commodification of animals, lack the power to stop this.

Cloners will even have the audacity to put on environmentalist airs. ViaGen, which currently charges $17,500 to clone a cow and $4,000 for a pig, and which, over the past few years, has provided more than 400 cloned animals to government scientists

Procedure Is Everything

Maryland Senator Barbara Mikulski accused the U.S. government of acting “recklessly”; but Mikulski’s concern was focused on a lack of labels to show which flesh and milk is which.

The European Commission has vowed to consult consumers before its final ruling in May. British supermarket chains are rushing to voice their policies against stocking cloned products, but how they’d identify products from clones’ offspring is a mystery.

A group whose role actually allows ethics to be considered did officially weigh in. After several months (months!) of internal meetings, of discussions with experts, and of gathering public views through the Internet, the European Group on Ethics of science and new technologies presented its opinion to the EC.

But the opinion of the ethics group speaks mainly of food safety. It wants “consumer rights and freedoms” respected even as it invokes the Amsterdam Treaty (which views animals as sentient beings) and the World Organisation for Animal Health’s “five freedoms” for animals: to behave normally and avoid malnutrition, fear, physical discomfort, injury and disease. Freedom from cloners didn’t make the list.

The ethics bureaucrats ask the Commission to say whether patents will apply, and to regulate it all through a “Code of Conduct on responsible farm animal breeding, including animal cloning.”

But a glimmer of hope remains, says the Daily Mail: The recently appointed environment secretary, Hilary Benn, is “a vegetarian who takes the suffering of farm animals particularly seriously.”

Sort of. Benn duly pledged to “wholeheartedly support beef, pork and chicken farmers and the meat industry” after being named Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs last summer.”

On the 19th of January, eight days after the European Food Safety Authority gave its preliminary nod to cloned groceries, I visited Benn’s website, entered “cloning” into the search field, and watched the result appear.

“Sorry, but you are looking for something that isn’t here.”