Protests by British university economic students against neo-classical economics highlight the notion that economic education is dominated by theories that defy practical applications and applications that cannot predict, prevent, and ameliorate periodic crises. Students learn economics from unverified and outdated theories, many contradicting one another, which leads to a confused understanding of the discipline and complicated approaches to resolving problems. Adding to the dilemma is that textbooks in Middle Schools, High Schools, and universities lack updates with recent knowledge and contain dubious propositions. It is time to examine several propositions that are prominent and dubious. This examination is not absolute, is intended to arouse discussion, and, hopefully, gauge if the theories should be restated or expunged from current academic learning, textbooks, and public discourse.

(1) Keynes Multiplier

(2) Philips Curve

(3) Disposable income

(4) Okuns Law

Keynes GDP Multiplier

One explanation of the Keynesian “multiplier is:

Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) = 0.8, when people get an extra dollar of income, and spend 80 cents of it. If the government increases expenditure by 1 dollar on a good produced by agent A, this dollar becomes A’s income. Suppose A spends the 80 cents on a good produced by B, then B would have an extra income of 80 cents. B would then spend 0.8 of this 80 cents, ie, 64 cents, on something else. This 64 cents becomes someone else’s income, and this someone will spend 0.8 of it. The process repeats itself. The GDP added to the economy is the sum of all the spending, 1 + 0.8 + 0.64 + 0.512 + … which has a larger effect than the 1 dollar that the government originally spent. In other words, the government spending is “multiplied”. Mathematically, the sum 1 + 0.8 + 0.64 + … is a geometric series. When you sum them up, it takes the form 1/1-MPC. For MPC = 0.8, the effect of the government spending is multiplied 5 times.

Can a fiscal multiplier of >1 exist? Has Keynes been misinterpreted?

When the government uses deficit spending (idle money that purchases government securities) to buy goods that are produced by A, then A has funds for producing additional goods to those already produced. If A spends the funds to buy goods from B, then A cannot produce additional goods. If B does not buy goods from C, then A’s spending can enable additional production by producer B. At no time does added production exceed the original spending and the GDP cannot increase by more than the original deficit spending.

Imagine a hypothetical system in which we have The Quantity Theory of Money

M×V=P×Y = GDP

where M= Money Supply, V=Velocity of Money, P= average price level, and Y = output, and the cost of goods sold (PxY) is in balance with the money (MxV) available to purchase the goods. The purchase of all goods continually generates new cycles of production of the same amount of goods. Add the new dollars (d) to the economic system. If all goods available remain at Y, then absorbing the added spending (d) dictates an increase in prices. If entrepreneurs use the added dollars to produce additional dollars of goods, the economy is in balance again ? (PxY)+d cost of goods is in balance with the available money supply (MxV)+d to purchase the goods. After (PxY)+d goods are sold in one round of spending, a new production cycle of (PxY)+d goods starts. Until more money enters the money supply, each production cycle cannot produce more than (PxY)+d value of goods.

The concept that A buys goods from B, which allows B to buy goods from C, and so forth, and that this increases GDP by more than the initial investment is implausible. Each is buying already produced goods with sufficient funds to purchase all the goods from the present production cycle. After all the goods have been purchased, others will be left with funds that are equal to the original expenditure. The GDP will only increase if these funds are invested in new production and that increase will, at maximum, be equal to the original expenditure,

Taken at face value, the Keynesian Multiplier hits a theoretical inconsistency; when MPC = 1, the multiplication becomes infinite, and the era of abundance has been reached. Actually, MPC = 1 signifies that, if the total of the original investment is spent, reinvested, and continues to be spent and reinvested, then, after an infinite number of rounds of spending, the total contribution to GDP of this investment (not the value of GDP) during the infinite period will reach infinity ? not surprising.

Rather than being a “multiplier,” the formula is a “divider.” Keynes’ formula states that, if not all available spending is used to purchase goods in a production cycle, fewer goods will be manufactured in succeeding cycles. Eventually, the public will no longer need these specific goods, and manufacturing of those goods will cease. Let MPC=0.8 in the investment series described above, and, with each investment cycle, the investment is reduced by 20 percent until it becomes nil and the company stops producing from the original investment. The production cycles, over the years, generate five times the original production. Instead of each investment being multiplied by 0.8, investment is reduced by 0.2. If MPC =1, then investment is entirely repeated in each investment cycle, and after an infinite number of cycles, total investment reaches infinity. The formula becomes logical and has no indeterminate value.

Keynes’ “investment multiplier” has never been shown to be true in practice and is not true in theory, yet it is used to justify policy decisions regarding government spending and is often quoted as a means to rapidly expand the economy. The “multiplier” only describes the way the system works ? sell the goods in one investment cycle, and, if there are additions to demand from additions to the money supply, start a new investment cycle that is greater than the previous cycle by the added demand and increased money supply. The renowned economist iterated in mathematical terms what all adequate company managers know ? if you turn over inventory quickly and replace it with new inventory, the enterprise can earn a lot of bucks.

Philips Curve

The Philips curve has had several transitions from its original concept. Its inception started from a paper in 1958 titled The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957, which William Phillips, a New Zealand-born economist, published in the quarterly journal Economica. Phillips described an apparent inverse relationship between wage changes and unemployment in the British economy during a one-hundred-year period. Because wage and price inflation seemed to move together, economists determined there must be a link between inflation and unemployment; when inflation was high, unemployment was low, and vice-versa. Historical data during the 1960s appeared to support the theory.

Supports the theory, but does not prove it is correct. Statistical coincidence is not proof.

Another statistical match.

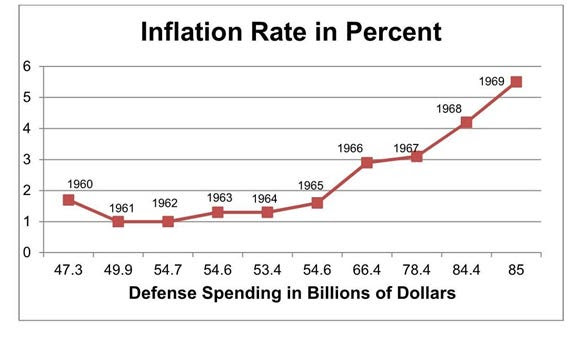

Plot defense spending during the same years and a similar curve emerges, where inflation is related to increased defense spending.

During the 60s, the United States increased defense spending, which increased employment and demand without increasing consumer goods production. Add the 1964 tax cut to the increases in defense spending and we have additionally increased consumer demand without increased supply. Could this have caused inflation?

Historical data from the Federal Reserve during the period from 1990-1999, which shows inflation and the unemployment rate decreasing together, refutes the Philips curve.

The record low unemployment and simultaneous low inflation rates during the late Obama and early Trump administrations also demonstrate the error of the Philips curve. The anomaly was extended into the Biden administration, where the inflation rate went to nine percent and unemployment reached a near-record low of 3.4 percent.

An explanation for inflation sometimes occurring when unemployment decreases may be more due to the euphoria in an expanding economy. As the economy looks bright, the bright start to borrow, which raises asset values and consumer demand. If additions to the money supply create demand that swells beyond production capacity, then prices are sure to rise. In addition, if the government continues to run deficits, which usually transfers savings to demand, the pressure on prices increases. During the Clinton administration, the government ran surpluses, which lowered the money supply and demand and resulted in stable prices.

Thus, it is incorrect to attribute decreasing unemployment to increasing inflation and vice-versa; it is the optimistic market and uncontrolled money supply expansion that causes inflation. As the industrial base and employment expand, costs should decrease — economies of scale grow, and fixed costs become a lesser cost of each production item, at least until the marginal revenue for each new worker starts to decrease.

Philips has thrown a curveball.

Disposable income

Disposable income is defined in textbooks as total personal income minus total personal taxes. This may be true, but analysis shows it is meaningless. The definition implies that taxation lessens disposable income and reduces spending in the economy.

Government spending transfers taxes back to the economy and provides income to workers. Other than profits made by corporations from government spending, interest payments (which may become another person’s income), foreign assistance that does not require payback or purchase of U.S. goods, and maintaining U.S. facilities in foreign countries, government spending from taxation winds up in the pockets of others as income. Individuals may have their disposable income reduced by taxes, and disposable income at one moment may be “income minus taxes,” but the disposable income of the entire population, in the long run, eventually remains almost the same as the original personal income. The original income reduced by taxes grows back again after the taxes are spent in the economy.

As a simple example, let us have the tax revenue used to support the income of government workers. In effect, disposable income has been entirely transferred from the private sector to the public sector but remains the same. The civil service workers also pay taxes and their taxes may support wages in a defense industry. Continue through continuous quick cycles of pay-as-you-go-taxation and government spending and we find that total income is much more than the originally taxed income and the final disposable income (DI) for the entire population is almost always equal to the original income. The regeneration of taxes and income follows the geometric series shown below, where t, a number <1, is the tax rate.

DI = (1-t) + (t- t2) + (t2-t3) + … (tn-1-tn) = (1-t) (1 + t + t2 + t3 +…tn)

If n goes to infinity, the equation becomes (1-t) / (1-t) = 1.

During a fiscal year, the government cannot, ad infinitum, invest all tax revenue, but can make, say, two turnovers of tax revenue to spending. DI then equals (1-t) + (t-t2) + (t2-t3), which becomes DI= 1-t3.

If t=0.2, then DI = .992, and almost all the original personal income is available as disposable income and that disposable income is available as purchasing power and spending.

Disposable income, as defined in textbooks as total personal income minus total personal taxes may be true, but analysis shows it is meaningless and that taxation does not lessen disposable income and reduce spending in the total economy.

Okun’s Law

Former Federal Reserve Chairman, Ben Bernanke summarized Okun’s Law:

Okun noted that, because of ongoing increases in the size of the labor force and in the level of productivity, real GDP growth close to the rate of growth of its potential is normally required, just to hold the unemployment rate steady. To reduce the unemployment rate, therefore, the economy must grow at a pace above its potential.

More specifically, according to [the] currently accepted versions of Okun’s law, to achieve a 1 percentage point decline in the unemployment rate in the course of a year, real GDP must grow approximately 2 percentage points faster than the rate of growth of potential GDP over that period. So, for illustration, if the potential rate of GDP growth is 2%, Okun’s law says that GDP must grow at about a 4% rate for one year to achieve a 1 percentage point reduction in the rate of unemployment.

Here we are faced with vague expressions – real GDP growth, GDP potential growth, and unemployment. How are they defined, especially unemployment? Is teenage unemployment the same as that of experienced workers? Does the gain in the former contribute as much to GDP as a gain in the latter? The essence of Okun’s argument is that reducing employment is not simple and easy; GDP must grow substantially to allow that to happen.

Okun’s Law is more a statement than a law and not one that has definite consistency or proof. Obviously, employment can be increased without an increase in the GDP – just decrease the working hours and hire more workers, as has been offered in several nations, or, tax and spend the revenue on the hiring of new government employees.

Edward S. Knotek, a vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, has examined Okun’s law. His Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank publication, How useful is Okun’s law? states

First among these is that Okun’s law is not a tight relationship. There have been many exceptions to Okun’s law, or instances where growth slowdowns have not coincided with rising unemployment. This is true when looking over both long and short time periods. This is a reminder that Okun’s law-contrary to connotations of the word “law”-is only a rule of thumb, not a structural feature of the economy.

This article has also documented that Okun’s law has not been a stable relationship over time. Part of this variation is related to the state of the business cycle: The relationship between output and unemployment is different in recessions and expansions, and recent expansions have been longer than average. Additionally, the data suggest that a weakening of the contemporaneous relationship between output and unemployment has coincided with a stronger relationship between past output growth and current unemployment. This finding favors versions of Okun’s law that are less restrictive in the timing of this dynamic relationship. These findings have practical applications. For instance, forecasting the unemployment rate via Okun’s law is much improved by taking into account its changing nature. These forecasts can be improved even more by allowing for a dynamic relationship between unemployment and output growth.

Despite some rationalizations that approve use of Okun’s law, Knotek’s review does not give Okun’s law a strong validation; mainly saying that, under some conditions, Okun’s law may apply, or, “If GDP increases substantially, unemployment may decrease,” which is not a powerful thought for academic expression.

Rephrased, Okun’s Law can be meaningful. Okun highlighted that the U.S. industry cannot accommodate new entries into the workforce and reduce unemployment without harboring substantial resources to increase the GDP. Omitted from Okun’s analysis is that entrepreneurs will not increase production and GDP unless they increase profits. Therefore, the statement should be more correctly rephrased as, “profits must grow at a higher percentage than normal to accommodate reduced unemployment,” which has been true.

The reduction of unemployment to record low levels during the Obama administration and continued reduction in the Trump administration showed that the GDP did not have to increase unusually fast to achieve the objectives. Government deficit spending took care of the entire matter.

Conclusion

Re-evaluating accepted economic concepts and correcting textbook explanations of vital topics are mandatory. Specious theoretical concepts deter proper thinking and can prove damaging to decision-making. Could this be one of the reasons why economic leaders have not been able to predict and prevent periodic recessions and economic catastrophes?