The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the hunting of black skins, signaled the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief moments of primitive accumulation. On their heels tread the commercial wars of the European nations, with the globe for a theatre.

— Karl Marx ((Capital 1: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production, ed. Frederick Engels, (New York: International Publishers, 1967), p. 703.))

The first fact of the history of American immigration is genocide: the displacement and destruction of the Native people of North America. This is part of the story of immigration, it is not some other, parallel history.

— Paul Spickard ((Almost Aliens: Immigration, Race and American History and Identity. (New York: Routledge, 2007). p. 25.))

Through the centuries, the Republic that eventuated in North America has maintained a maximum of chutzpah and a minimum of awareness in forging a creation myth that sees slavery and dispossession not as foundational but as inimical to the founding of the nation now known as the United States. But, of course, to confront the ugly reality would induce a persistent sleeplessness interrupted by haunted dreams, so thus far this unsteadiness has prevailed.

— Gerard Horne ((The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, and Capitalism in Seventeenth-Century North America and the Caribbean, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2020), p. 191.))

Destitute Peasants Leave Norway For The American Frontier

On April 21,1885, a steamship left Christiana (now Oslo), Norway for Liverpool, England and then on to a 9-day voyage for North America. Among the ship’s 1500 passengers, most of them in steerage, which meant below the water line, no windows and only scant light and ventilation, was the recently widowed Elizabeth Thorson and her five children. The youngest was ten-year-old Emma who would become my grandmother. Elizabeth’s decision to emigrate was an act of awe-inspiring courage and resolve even though she had more than ample reason to fear for her family’s future if she remained in Norway and realized that the American frontier was her only option.

There is insufficient space to detail Norway’s rigid social order that allowed no opportunity for advancement. Suffice it here to say that the apex of the class system consisted of an aristocracy of professional men who controlled the economy and the government. Their rule included the hierarchy of the powerful and reactionary Norwegian state Lutheran church for which it was unlawful not to be a member.

Due to topographical dictates, only 3 percent of the land was tillable and most of that was held by the King (the “King’s Commons”), the church and other large landowners. Property relations were such that the vast majority of rural folk were landless. Although some resistance sprang up in the 1850s, it was easily crushed by the state’s large-scale police action.

Some 85 percent of the population was rural, consisting of small farmers, cotters (poor tenants) and servants. However, unlike the English feudal dispossession of the peasants from their land and replacement of them of them with sheep which occurred in the sixteenth century in what became known as the enclosure movement, Norwegian peasants lacked even the option of selling their labor to toil in factories under debasing Dickensian conditions.

In 1825, the first organized emigration of Norwegians occurred when a small group of religious dissidents, many of them Quakers, departed from Norway on the sloop Restauration and after a hazardous three-month crossing landed in New York harbor, most of them eventually settling in rural New York state. In the 1840s, immigrants did a reverse journey on a promotional tour sponsored by U.S. financial interests to spread “America fever” and this prompted more departures.

Subsequently, the first major wave occurred from 1866 to 1873 (111,000) when income inequality in Norway reached unusually high levels. This was followed by several years of depression, agricultural disasters causing famines, mounting debts and forcing people to sell themselves into indentured servitude just to survive. Intrepid voyagers like Elizabeth joined the second surge from 1879-1893 (250,000), that averaged more than 18,000 annually, such that only Ireland had a higher rate of emigration.

A third and final wave from 1900 to 1910 saw more than 200,000 departures, in part due to a substantial population increase. Altogether, nearly one million people emigrated to North America during the second half of the century. Whatever else might be said about them later it’s indisputable that this was an emigration of severely oppressed people whose lives had become unbearable. They faced two choices: emigrate or starve.

For a visual, albeit fictional sense of this period, I recommend two internationally-acclaimed films, The Emigrants (1971) and the sequel, The New Land (1972), that graphically convey the travails of, in this case, Swedish emigrants in a manner that closely mirrors that of my Norwegian ancestors. ((Directed by Jan Troell and starring Liv Ullman and Max von Sydow, they are based on Vilhelm Moberg’s novel, The Emigrants. During the film’s production, Troell made extensive use of locations in Minnesota. For a brief but poignant sequence from early in the film, see Liv Ullmann, On the Emigrants and The New Land.))

My take is that my ancestors were pushed and pulled by forces over which they had little to no control over forces which sociologist Karen Hanson contends, “dislocated peasants and dispossessed Native peoples.” ((Karen V. Hanson, Encounter of the Great Plains (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) p. 238.)) Hanson doesn’t go into specifics about these “missing pieces” but prefiguring later discussion and as one other astute observer explains, upon arriving in North America, the ends were unchanging. That is, the intentions of those responsible for colonialism was “to shore up access to Indigenous people’s property for the purpose of state formation, settlement, and capitalist development.” ((G.S. Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014) p. 25.))

The genesis of these global forces originated far in advance of England’s rise which eventually led to London’s invasion of North America, settler colonialism, slavery, white supremacy and 1776. The continuity continues apace today with the U.S. capitalist global empire. ((I’m referencing the work of the historian Gerald Horne. The importance of his masterful, original, and path-breaking studies on these origins cannot be overstated. See, especially, Gerard Horne, The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2020); and on the seventeenth century, Horne.)) As such, I’ve tried to be mindful of Frank Joyce’s wise counsel that “Knowing how the system was created is essential to working out how to take it apart and reconstruct it.” ((Frank Joyce, “Exploring America’s Hidden Past as a Center for the Slave-Breeding Trade,” Caricon, 9/16/2016. In terms of steps toward re-education I profited from viewing “Exterminate All the Brutes,” the 4-part series written and directed by Raoul Peck. It’s based, in large measure, on Sven Lundquist’s eponymous book, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous People’s History of the United States and Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past.))

In what follows I attempt to revisit and unpack the reasons for my previous externally manufactured ignorance and vast storehouse of misinformation about the reasons for my ancestor’s arrival here and in dispossessing the indigenous people. My conceit is to insert instances of personal memoir in hopes they will help explicate the subject. I discuss the capitalist logic of dispossession, invasion, elimination, role of settlers, the “whiteness” factor, mascots, state policies of brainwashing Indigenous children through boarding schools, cultural misappropriation, assimilation, revisionist history and the future.

What lessons might we learn from deconstructing this history and begin doing what Kenyan novelist and postcolonial scholar Ngugi wa Thiog’o describes as “decolonizing the mind.” He used it to explain how colonized people needed to liberate themselves from an insidious, brainwashing colonial mentality that all things “Western” were superior to being indigenous. ((Ngugi wa Thiong’o. See his Decolonizing the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1986).)) Here I’m suggesting that we descendants of a colonial state also need to liberate our minds no matter where that leads. It’s an awkward, uncomfortable, and oftentimes gut-wrenching undertaking, but we need to critically reconsider what we’ve internalized about U.S. history. We need to reconstruct it because substantial portions were lies. Absent that deprogramming, the most propitious path for moving forward will remain elusive.

Finally, in initiating this exploration, my intent was not to shame, blame, exculpate or pronounce absolution on settlers but to find at least a close approximation of the truth. Further, I readily acknowledge that over time my ancestors assumed a white identity with all its attendant benefits, many of which adhered to their descendants, including, of course, myself.

My Grandparents Obtain Land

My grandfather, Tobias Aanonson, also of peasant stock, was not the eldest son in the family therefore not in line to inherit any property. His prospects in Norway were nil and he left Norway for Minnesota during that same period and began toiling as a lumberjack in the state’s North Woods.

Prior to marrying Tobias, my grandmother Emma had been sold into indentured servitude by her indigent mother to a wealthy family owning a boarding house in northern Minnesota who paid for her steerage tickets. There, she labored under harsh and restrictive rules and it was common for young girls to perform this work under 5-7-year contracts but in many cases the servitude for a child would last until maturity. Conceivably, the term for my grandmother continued until she reached 17 and married my grandfather who was 15 years her senior. Family anecdotes have it that her experience as a boarding house servant was embittering and exacted an emotional toll for the remainder of her life. One result was bitterness toward her mother and another was that she despised indoor work like cooking and cleaning. These were left to the five daughters as Emma labored outdoors alongside Tobias. I suspect that variations on this story could be recounted by many others.

My grandparents began farming in southern Minnesota in 1892. Given that the best land was already claimed, documents show that they purchased their plot from someone who had almost certainly received it “free” under The Homestead Act of 1862, signed by President Abraham Lincoln. In a speech in February, 1861, Lincoln had told the nation that “wild lands of the country should be distributed so that every man should have the means and opportunity of benefiting his condition.” Indigenous people did not fit this category.

With their passage, the Homestead Acts became, “unquestionably the most extensive, radical redistribute government policy in US history” as they granted 246 million acres to 1.6 million individuals, some ten percent of the land in the United States. ((Keri Leigh Merritt, “Land and the roots of African-American poverty,” Aeon, March 11, 2016.)) In terms of Norwegian-Americans, it’s impossible to overstate the importance of the Homestead Act because “Individuals without property to earn a living in their home country now had an opportunity to become landed.” ((Terji Mikael Hasle Joranger, “The Creation of a Norwegian-American Identity in the USA,” Journal of Migration History 5 (2019) p. 489-511.)) Claimants had only to be U.S. citizens, intend to become one, file an application, pay a fee of $18, improve the land while remaining on it for five years and file a deed of ownership.

In 1863, some 20,000 claims were immediately filed in Minnesota and the total acreage was the largest allotment for any state in the nation. Less well known is the fact that all the elements needed to actually start a farm were expensive, roughly $795 (or $17,500 in 2003 dollars) and thus beyond the reach of many. And we learn from the National Archives, that through massive fraud, “Most of the land went to speculators, cattlemen, miners, lumbermen and railroads.” ((Lee Ann Potter and Wynell Schmel, “The Homestead Act of 1862,” Social Education, 61,6 (October, 1997); Ray Allen Billingston, Westward Expansion: A History (New York: Macmillan, 1960).))

Betty Bergland, professor emerita of history at the University of Wisconsin/River Falls, makes the important, clarifying observation about the Homestead Act that it was primarily the federal policies of war, removal, exile and reservations that enabled Norwegian immigrants to “claim land, gain citizenship and opportunities to pass that along to succeeding generations.” ((Betty A. Bergland, Norwegian migration and displaced peoples: Toward an understanding of Nordic whiteness in land-taking. Jana Sverljuk, et al. Nordic Whiteness and Migration to the USA (New York: Routledge, 2020).)) Again, as will be addressed later, the motives behind these policies require further explication.

The “pull” of the land was also furthered by the Federal government’s after-the-fact legalization of “squatting” on unsurveyed land, boosterism from land agents, government officials, and town promoters, ads appearing in local newspapers and letters from immigrants themselves sent back to Norway. In the 1890s and early 1900s, my mother and her seven siblings were born and raised on one of these parcels of land near Belgrade, Minnesota.

I should state that my Norwegian immigrant ancestors are neither abstract “settler colonialists” to me nor tinged with its pejorative connotation. Perhaps part of my inability to conjure up that image stems from fond memories of summer visits to my grandparent’s farm in Minnesota with its plain, wood frame farmhouse, heated only with a wood-burning stove in the kitchen. Across the farmyard, I recall outbuildings that included a sagging, red painted barn with a hay loft and empty stalls. A ramshackle poultry house with cobweb laced broken windows but still containing some scattered chicken feathers, an aging tractor, two-hole outhouse and a rusty water pump that required priming. (Note: My mother told me that rope was strung between the house and the barn for safe passage for doing chores during whiteout winter blizzards.)

One experience indelibly imprinted on my mind occurred when I was about seven or eight years old. My Grandpa Tobias let me be his “hired hand” for the day and we started in the wheat field. My assignment was to gather and stack several bundles of wheat together to form a shock. After a long morning in the field I’d only managed to assemble one vague facsimile and it was falling apart due to my inept application of baling twine. On our conversational-less walk back to the house for lunch, my Grandpa uttered a few words in Norwegian and pressed a silver fifty cent coin into my palm. The coin disappeared soon thereafter, but a few years ago, I purchased three of them, all dated 1951, to pass along to my grandchildren one day along with a story about their great, great, grand-father. (Note: When the farm was sold after my grandparent’s death, no proceeds were passed along to my mother and her siblings and instead went to pay taxes.)

Settler’s Preconceptions?

Some evidence suggests that the newcomers believed a vast virgin wilderness was waiting to be settled, a “land without people for people without land,” the founding deception so effectively employed by Zionists to lure unsuspecting Diaspora Jews to Palestine. Another interpretation is that settlers were under the impression that the Natives had moved on long before the settlers arrived.

As will be explored in some detail later, we know that in the 1860s, Norwegian journalists helped spur a sizable influx of Norwegians to North Dakota and Minnesota. For just one example, aware of the major economic collapse in Norway and its desperate land-poor peasants, Paul Hjelm-Hansen, a journalist employed by the governor of Minnesota, portrayed the region as an agricultural oasis “with places for many thousand farmers.” ((Kathleen Ruth Brokke, Transformation of the Red River Valley of the North: An Environmental Study. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, December, 2015, p. 53-54.)) Minnesota and North Dakota were magical landscapes where “one only had to arrive, put plow in the ground, and throw seeds into the rich black earth.” ((Kathleen Ruth Brokke, Transformation of the Red River Valley of the North: An Environmental Study. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, December, 2015, p. 53-54.)) Hjelm-Hansen’s articles appeared in several Norwegian newspapers in 1869 and had the desired effect.

Whatever their preconceptions might have been, one authoritative source explains that as immigrants surged into the Minnesota territory they found that the land was “already settled by Native Americans.” Due to a devious, semantic sleight-of-hand this was taken to mean “the right of occupancy, not the right of ownership.” ((Susan Granger and Scott Kelly, Historic Context Study of Minnesota Farms, 1820-1860, Vol.1. June, 2005.)) According to Swedish scholar Gunlog Fur: “The fiction of empty land available for cultivation required an active denial of an Indian presence, even when they were everywhere… It also served to deny the integral role of violence in the expansion of white settlement across the North American continent. ((Gunlog Fur, “Indians and Immigrants,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Spring, 2014, 33/2. 58.))

Two brief scenes, highlighting a few fairy tale assumptions are found in the aforementioned film, The Emigrants. In the first one, two boys are excitedly reading a promotional booklet about the promising New World and one exclaims “Even slaves have a higher standard of living than most European peasants. I want to sign up to be a slave!” In the second, some Scandinavian immigrants are on a paddle boat heading across the Great Lakes toward Minnesota, when one expresses amazement at seeing wealthy, first-class passengers strolling on the upper deck. A fellow passenger patiently explains that the U.S. is not at all like the class society they fled because in America “These people who have been here long enough are already rich. We’re still poor because we just got here. It takes a little time.”

The historical record reveals soon enough that many of these naive settlers began experiencing the “promised land” as a cruel lie when the power of capital emerged with the likes of robber barons Cornelius Vanderbilt, J.D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J.P Morgan. In short order, a substantial number of farmers lost their land as the very wealthy, white 1% claimed ownership of over half the property in the country and one fourth of the nation’s wealth. By 1900, that grew to 10 percent owning 90 percent of the country’s wealth.

In response, class conflict began with a railroad strike on July 16, 1977 and the consequent Great Upheaval of workers was met with massive state violence against strikers, workers and protestors over the next three decades.” ((For a trusted source on this period, I can recommend Jeremy Brecher, STRIKE (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2020, revised and updated) which I regularly assigned as a text in my courses. Also, Nell Irvin Painter’s highly accessible treatment, Standing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877-1919. (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989).)) Historian Mary Neth captures what this meant for family farmers: “In rural America, the development of industrial capitalism directed collided with a family-based labor system” and many people were displaced, “…including farmers on small farms, tenants, hired workers, and unpaid women and youths. ((Mary Neth, Preserving the Family: Women and the Foundation of Agribusiness in the Midwest, 1900-1949 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), p. 3 and 5, as cited by Hanson, p. 219.))

Foreshadowing a position amplified later in this essay, I’m suggesting that the immigrants had performed their indispensable function for the capitalist colonial state in settling expropriated land, increasing population numbers and legitimizing the property state. It only remained for elites and their enablers to retain settler allegiance via myriad forms of scapegoating, repression, and propaganda, especially a stepped-up emphasis on “whiteness.” Concurrently, if not literally eradicating all the remaining Indigenes, they began devising methods to commence cultural genocide.

Beneficiaries Of Government Policy

By the year 2000, the number of adult descendants of the original Homestead Act recipients numbered at least 46 million people or a quarter of the US adult population, virtually all of them white. ((Keri Leigh Merritt, “Land and the roots of African-American poverty,” Aeon, March 11, 2016.)) Only 5000 African-Americans benefited from the 1862 Act. It’s beyond disputation that these government programs and policies funneled myriad opportunities to white people at the expense of others. As one student of the subject points out, “For the wealthy, inheritance provides a genealogical distance from conquest, genocide, and colonial slavery that offers a cover of ostensible innocence and launders accumulated incomes.” ((Aloysha Goldstein, “On the Reproduction of Race, Capitalism and Settler Colonialism,” Race and Capitalism: Global Territories, Transnational Histories, October, 2017, p. 45.)) Confining ourselves solely to approximate economic calculations and excluding cultural capital which is immensely important but harder to determine, land acquisition itself translated to several trillion dollars.

This bookends the dollar value that white Americans profited from unpaid Black slave labor with those estimates starting at $1 trillion dollars, a sum attaching graphic numbers to “white privilege.” By contrast, there are three million descendants of the native peoples who once inhabited this land and we know that indigenous people as a whole have the highest poverty rate among all minority groups in the United States.

In the South, there were some four million emancipated African-Americans in 1865 and the Southern Homestead Act (SHA) was passed on June 21, 1866. The Act opened some 46 million acres of public land — much of it unsuitable for farming because of swamps and forests — in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi. African Americans were given priority until January 1, 1867. However, several insurmountable obstacles blocked recently freed slaves from benefiting from it. The most egregious barrier was that at the end of the war, former slaves had been tricked, cajoled or forced into signing labor contracts, often to work on former plantation land as sharecroppers where they also accrued steep debts.

Breaking a contract resulted in onerous consequences, including the chain gang. As historian Keri Leighton makes clear, Blacks were “locked into these contracts until the very day when they would stop receiving special homestead benefits” As a result, by 1869, only 4,000 African Americans succeeded in staking a claim under the SHA and only 1,000 property deeds were issued. Again, most of the recipients were white. ((Keri Leigh Merritt, “Land and the roots of African-American poverty,” Aeon, March 11, 2016.)) The law was repealed in 1876. If it’s not been done, a research project on the fate of the original recipients and their descendants would be valuable. My hypothesis is that because of state sanctioned oppression and myriad forms of informal white supremacy, any positive gains were stillborn.

The Logic Of Indigenous Removal

In terms of Indigenous removal, the picture will remain opaque if we don’t grasp that the logic of dispossession was not premised on race but on where Indigenous people lived. In Deborah Bird Rose’s pithy observation, “To get in the way of settler colonialism, all the victim had to do was stay at home. ((Deborah Bird Rose, Hidden Histories, (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1991), p. 45.)) The Australian anthropologist and ethnographer Patrick Wolfe, famously argued that “It is ‘territoriality’ that remains the colonialist’s irreducible element, not race, or religion, ethnicity, grade of civilization, etc. ((Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research, Vol.8, 2006, pp. 387-409.))

This operates through a “protracted invasion” and the logic of elimination” that necessitates the destruction of indigenous people — but not necessarily genocide, as land is the objective. Eventually, this even allows for granting limited individual rights and cultural protections as these help rationalize expropriation, tie the indigenous remnant to the state and help to convince white people that they are superior and the more deserving occupants of the land.

The methods for violently oppressing Indigenous peoples and Blacks were different. On the one hand, as noted, the colonialist state’s policies of extermination and forcible relocation of Indigenes was for the singular purpose of seizing land. To reiterate, in political scientist’s Walter Hixson’s concise wording, this was a “winner takes all” proposition. On the other, the Black experience centered on enslaving, breeding and violent control in pursuit of cheap labor. Their bodies were commodities. Both cases involved massive state terrorism, rooted in the categorical capitalist imperative of “Expand or Perish” — by any means necessary. It’s in this specific economic context that we have the artificial social construction of white supremacy and race.

After the Civil War, for Blacks it was Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan, exclusion from key provisions of the New Deal, formal and informal segregation, COINTELPRO, the prison-military complex, Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” a racially biased “drug war” leading to the incarceration state, revival of Jim Crow stereotyping, “super-predators,” decimation of black wealth, racist police violence, and the complicity of the black mis-leadership class. For Indians, after 1890, it was more broken treaties, continued dispossession, slaughter, exile, the reservation, writing Indigenous people out of history, cultural appropriation, commodification and forcible assimilation. The latter means that 80 percent of Native Americans reside off the reservation, primarily in large urban areas.

Assimilation As A Disingenuous Euphemism

Assimilation deserves special attention in that nothing approaches its magnitude and unspeakable cruelty more than the cultural genocide practiced by Indian Boarding Schools. Their purpose, in the pithy words of Gen. Richard Henry Pratt, who founded the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, was “To Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Over the years, hundreds of thousands of children were taken from their families and communities, beginning with the Civilization Act of 1819 which sought to introduce children as early as six years old to “the habits and arts of civilization.” Uncle Sam paid bounties to those capturing runaways from the schools. Later, under the Indian Appropriation Act of 1851 and the Peace Act of 1869, these schools went off-reservation and parents were not even allowed to visit their children because it might retard the pace of the civilizing process. The children were schooled in the importance of private property, material wealth and Christianity. David Wallace Adams was not engaging in hyperbole when he titled his book on Indian Boarding Schools, “Educating for Extinction.”

By 1926, more than 60% children or 83 percent of Indian school-age children were attending these boarding schools. Coincidentally, in 1924, the government had imposed full citizenship on Indigenous peoples, also meant to foster assimilation in the form of nationalism, patriotism, and accepting the “American Way of Life” — while further distancing themselves from their tribal identity, culture and language. As for the boarding schools, it’s almost unfathomable to realize that parents did not gain the legal right to deny their children in one of schools until 1978 with passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Indigenous Dispossession

It’s not generally known that for much of the West, homesteading was not the primary means of dispossession. It may sound like a difference without distinction but the 1830 Indian Removal Act used the U.S. Army to force several tribes to relocate west of the Mississippi River in order to accommodate white settlers. In Nebraska, the federal government had already seized some 30 million acres from Nebraska tribes before 1862. Further, in many places, white vigilantes and local “militias” acted on their own in tracking down and murdering Natives with the government a convenient few steps behind.

In Minnesota, some indigenous land was taken by the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux, signed on July 23, 1851 under which the Sioux were forced to cede 24,000,000 acres of their territory and “relocated” to temporary reservations along the Minnesota River. Payments for the land proved to be far less than promised and then were halted altogether. Nevertheless, in the Dakotas and Minnesota, after 1862, homesteading played the major role in dispossession.

In 1862, the Dakota Sioux, in retaliation for years of mistreatment by whites and facing imminent starvation, embarked on an implacable, fierce, but ultimately futile attempt to drive out the colonial invaders. They were crushed by the U.S. Army in the Dakota War of 1862 and this culminated on December 26, 1862 with the largest mass execution in American history. After a hastily convened military commission and totally unfair trial, 303 Dakota were sentence to death and on signed orders from President Abraham Lincoln, thirty-eight of them were hanged from a giant scaffold in the center of Mankato, Minnesota (another town in which I lived) an event attended by 4,000 spectators. Just as the trap door began to open, each one called out his or her name in native tongue and declared “I’m here. I’m here.” (Note: Confederate generals killed over 400,000 union soldiers. Lincoln never ordered the execution of a single one.)

After the hanging, the remaining Dakota were evicted from their ancestral homeland to prison camps in Iowa, others were forced to march barefoot in the snow to Crow Creek, SD. Many died in prison or in a concentration camp in Sisseton, SD while still others escaped to Canada. A bounty was placed on the scalps of every Dakota man, woman and child. The hangings followed six weeks of fighting between Indigenous peoples and the U.S. Army that had signaled the advent of three decades of fighting between Indigenous peoples and the U.S. government across the Great Plains. Several accounts agree that many Norwegian-Americans began voicing increased antipathy toward Indigenes after 1862.

In 1877, the Dawes Act was enacted and led to catastrophic consequences for Indigenous people. Named after Sen. Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, Dawes left the Sioux Nation broken into isolated, fragmented small reservations surrounded by immigrants. Each Indian head of household was given a plot while the remaining substantial tribal land was declared “surplus” and made available to white homesteaders. Under the Dawes Act and the “Dead Indian Act” of 1902, 100 million more acres were lost, some 65 percent of reservation land. By 1920, all the prime land had been taken over by non-Indigenous ranchers.

In February, 1890, the federal government broke a treaty with the Great Sioux Nation and divided the reservation in North Dakota into five smaller ones. The primary reason was to make more land available for settlers but it was meant “to break up tribal relationships” and “conform Indians to the white man’s ways, peaceably if they will, or forcibly if they must.” ((Anthony F.C. Wallace, “Revitalization Moments: Some Theoretical Considerations for Comparative Study,” American Anthropologist, 58, (2) 1958. pp. 264-81.))

On December 29 of the same year at Wounded Knee Ridge in South Dakota, the U.S. Army surrounded a Lakota Sioux encampment at Wounded Knee Ridge in South Dakota. After setting up Hotchkiss guns that fired one shot per second, the troops proceeded to mow down some 300 unarmed old men, women and children. After this bloody massacre, the government awarded Congressional Medals of Honor to 20 of the soldiers for demonstrating “conspicuous and intrepid bravery.”

Skirmishes punctuated the next several years but Wounded Knee demarcated the “closing of the frontier.” After this final military defeat of the Indigenes, white identity and a host of other factors merged to rationalize dispossession. However, I will tip my hand and suggest examining these factors should not divert and obscure our attention from the fact that the United States was founded as a capitalist state colonial entity. The state and its enablers were the legitimating authority for genocide and whereas “Whiteness” assumed a critical instrumental role, it was not the determining one. As I will argue later, class retains primacy over other important, coterminous but ultimately among auxiliary secondary factors in our search for the ultimate causal explanation.

Today, two of the five poorest communities in the United States — Allen #1 and Wounded Knee #5 — are located in Oglala Lakota County which is totally contained within South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation. The county also has the lowest life expectancy, highest unemployment, and at $8,768, is the poorest in the United States.

The “Fighting Sioux” Mascot

Although I also lived in Minnesota and South Dakota, my formative years were spent in Fargo, North Dakota along the Red River of the North on the eastern border of the state. The city was named for William Fargo, an owner of the Wells-Fargo Express Company and one the directors of the Union Pacific Railroad whose tracks ran through the center of town and held up traffic three times a day. When UP engineers and surveyors first arrived, they were accompanied by U.S. Army officers. This continuing symbiotic partnership between the capitalist state and big business was exemplified by Congress granting rail companies 10 million acres of free public land in Minnesota, amounting to 20 percent of the state’s land area. It was, of course, in the interest of railroad officials to lure immigrants to the region because it increased the value of their line. The construction of Fort Abercrombie in 1857, just thirty miles south of Fargo and the first fort in North Dakota, helped prompt immigrants to surge into the region through the “Gateway to the West” and stake their claims. Fort Abercrombie was followed by six more military bases across the state in the 1860s and early 1870s.

A program closely related to the aforementioned Dawes legislation was The Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862 and expanded in 1890, which gave the proceeds of the sale of federal land expropriated from indigenous tribes to state governments to set up land grant colleges and universities. Our house in Fargo was not far from North Dakota State University (NDSU), a college established under The Morrill Land Grant Act. As with so much else, I was totally ignorant of this history and if I thought about it all, I probably felt Morrill was actually something that the government got right.

NDSU’s athletic teams are called “The Bison” or “The Thundering Herd” and their traditional in-state rival is the University of North Dakota (UND), “The Fighting Sioux.” After a seven-year legal battle with the NCAA and a state-wide vote, in 2015, UND’s name was officially changed to the “Fighting Hawks” in 2015. Opponents of the change said the logo showed “pride and tradition” but the 21 Native American-related organizations argued that it disrespected their culture and the strongest advocates for the name change were members of the Standing Rock Tribe.

Even in 2021, the Fighting Sioux logo remains on seats in the hockey arena, on a huge statue of Sioux Chief Sitting Bull sitting astride a horse outside the arena, and many fans still wear clothing adorned with the vintage logo to games. This Indigenous cultural appropriation was perfectly normal to me and reinforced stereotyping while simultaneously having a damaging effect on Native Americans’ sense of self-worth, self-confidence and self-image.

In the words of Paul Chat Smith, a curator at the National Museum of the American Indian, “Multiple studies have shown that these mascots, which are stereotypes of Native peoples, cause real damage.” The American Psychological Society concurs and in 2005, after citing voluminous research on self-esteem and social identity development, called for “the immediate retirement of all-American Indian mascots, symbols, images and personalities by high schools, colleges, universities, athletic teams and organizations” A.P.A. President Ronald Levant added these negative lessons “are sending the wrong message to all students.” ((Andrew C. Billings and Jason Edward Black, Mascot Nation: The Controversy Over Native-American Reproductions in Sports (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2018); Laurel R. David Delano, Joseph Gone & Stephanie Frybers, “The psychological effects of Native-American mascots: a comprehensive review of empirical findings,” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Education, June 8, 2020; For a revealing interview with a female, Native-American, Division 1 basketball player, see, Jaden Urban, “Offensive Mascots Take Toll on Indian Athlete,” Indian Country Today (n.d.).))

Emblematic of its continuing currency is the fifteen-year controversy that was only resolved this year in nearby Radnor, Pennsylvania. The issue that divided this affluent community and its highly rated high school (#4 in the state) was the high school’s mascot: An American Indian warrior known as the Radnor “Red Raider” Starting in 2016 and again in 2018, the school newspaper began condemning the “Tomahawk Chop” performed at athletic contests and advocated rethinking the mascot. After several contentious public meetings and vehement opposition from older alumni, a list of names, minus Red Raiders, was whittled down to four, and students chose the name “Raptors.” In 2020, some 2,000 schools and institutions continue to retain these mascots. In my home state of Pennsylvania, 64 high schools still retain Indigenous mascots and names.

Indian Head Penny For Your Thoughts?

A personal example that might seem innocuous on first glance and not fit the mascot designation, is the Indian Head Penny. Having Native-Americans on my mind in recent months, I recalled that in my youth I’d been given a small collection (10-12) of these Indian-themed coins from my mother who’d probably received them from her parents.

The coins were produced by the United States Bureau of the Mint from 1859 to 1909 when they were replaced by the Lincoln penny. James Longacre, Chief Engraver of the Philadelphia Mint, designed the coin and used the facial image of his daughter Sarah to depict “Lady Liberty,” an Indian princess adorned in a traditional Indian headdress. Longacre found nothing morally objectionable or inconsistent about the image and certainly not “repulsive to be associated with Liberty.” He said the implicit message was that “We were never in bondage to anyone.”

The Mint’s director loved the depiction and wrote that the new “Indian Head would present an ideal of America — the sweeping plumes of the North American Indian giving it the character of North America.” There was some initial grousing about the image of a “savage” Indian on the face of America’s legal tender but using “a sanitized Caucasian girl with Greek features to represent an Indian made it okay.” She was in fact a “Good Indian,” the direct opposite of those marauding ones who were resisting the gifts of civilization proffered by the colonialist state. ((Bob Schmidt, “The Indian Head Penny,” Newspaper Rock, December 18, 2008. The author is an expert on several Native-American issues and contributor to Indian Country Today.)) The fact that the coin was being praised and circulated during the period when the mass slaughter of Indians was in overdrive qualifies the statements as an early example of chutzpah.

Lest one think this is now discredited thinking, in surveying sites that buy and seek rare coins in 2021, I found the consensus view remains that the “The Indian Head Penny embodies the bold, independent, timeless spirit as much today as when was first minted in 1859.” Not only does it reflect “Native Americans’ unique role in shaping U.S. history,” it’s motif “honors the United States’ Native American heritage” and “When it comes to American coins it is hard to get more American than Lady Liberty and Native Americans.”

In writing about the motives behind employing such images, Yale historian Alan Trachtenberg concludes they were about the fact that “Indians had been slaughtered for the sake of the new race of Americans; they must be resurrected and commemorated, their ‘pure’ image pressed in gold” — or in this case, copper. ((As cited by Rick Green, “What It Means to Be an Indian in America,” The Hartford Courant, January 9, 2009.)) The coin sanctified manifest destiny and conveyed the message that Indians were done an enormous favor for which they were ungrateful. Finally, to return to my earlier point, the Indian Head Penny was “an early version of an Indian mascot,” some of which could be found over a century later in valuable rare coin collections. It’s another image lodged in America’s delusional, collective, colonized mind.

Another egregious example to which I was oblivious was that the two states admitted to the union on November 2, 1889, were North and South “Dakota,” appropriating the name the Sioux nation called itself and meaning “friends or allies.” Today, about half the names of American states are Indigenous in origin, a not subtle assumption of ownership whereby “white dominant society assumes control of the meaning of Nativeness.” It justifies the “maintenance of a system of domination and control — whether intentionally or unintentionally — where white supremacy is safeguarded.” ((As cited by Rick Green, “What It Means to Be an Indian in America,” The Hartford Courant, January 9, 2009.)) in short, this was and remains a crude attempt to sever Native people from their cultural heritage as they are subsumed by white supremacy and are continually reconquered by other means.

Finally, there’s a long history of cultural misappropriation on behalf of commercial projects and one egregious example is the travel industry. From 1933 to 1950 there were “Wigwam Motels,” mostly in the Southwest, the Wooden Indian Bar in New York City’s Americana Hotel only closed in 1992 after protests and in 2017, Airbnb issued an apology for an ad promising a “true Sioux” experience in Joshua Tree California even though no members of the tribe ever resided there. Squaw Valley, site of the 1960 Winter Olympics, is changing its name after complaints from Native Americans that the name is a racist and sexist slur. Just this year, an Arizona businessman proposed building a massive glamping resort on the outskirts of Flagstaff. Called “2 Guns,” it would have all the usual amenities but also feature 70 tepees, 12 hogans and incongruously, 43 Conestoga wagons. The premise was that “authenticity” would lure well-heeled tourists. ((Karen Schwartz, “Is Travel Next in Fight Over Profiting from Indigenous Culture?” The New York Times, August 9, 2021, B5.))

My Episodic Encounters With “Indians”

In terms of my personal experience, I had few direct contacts with Indians — or were they simply unseen? That five percent of the state’s population was scattered on five reservations and North Dakota remains the only state with a majority of Indians living on reservations. I recall a few Indians hanging out on one seedy downtown street in Fargo where they would sometimes purchase liquor for under-age guys and be repaid with a bottle of ultra-cheap Thunderbird, what we called “bum wine” and associated it with Indians.

Here, one anecdote that merits retelling concerns Fort Yates in North Dakota. It was constructed to keep the Indians in line and after Col. George Custer’s “tragedy” at the Battle of Little Big Horn” on June 25, 1876, the number of troops stationed at the Fort peaked at 3,000 and 65 buildings. The fort was named to honor Captain George Yates who died in the battle. Also, after Sitting Bull was killed on December 14,1890, he was buried at Fort Yates and earlier, white missionary assimilationist nuns had started an Indian boarding school there in 1877. I mention this background because like so much else, I was totally ignorant of this history and only several decades later did I began to recognize more examples of constructed Indian-ness, really, manufactured ignorance, for the racism they embodied.

In 1961, as a high school, cross-country runner, I competed in the state xc championships against the storied runners from Fort Yates, the perennial favorite to win the title. A town some 60 miles from Bismarck, Fort Yates had a population of 1100 at the time which has now dwindled to less than 200. Before the race, my coach cautioned me that my major competition for individual honors was an Indigene from Fort Yates. Curious, a few minutes before approaching the starting line, I asked a member of his team to point him out. His teammate replied with a laugh, “Oh, he was too hungover this morning and missed the team bus.” I mention this because that conversation undoubtedly reinforced the idea in my mind — one common at the time — that Indians were weak, unreliable and naturally predisposed toward alcoholism. I had internalized the dominant society problematizing of Indigenous youth that contributed to stereotyping of Natives as inferior to whites. I went on to win the race but is it totally implausible to speculate that the outcome was a symptom of the colonial condition?

Whether or not it was applicable in that particular case, I was totally oblivious to the historical context which is summed up by two authoritative researchers on alcohol use in Indian country: “What is not recognized is that alcohol use and even suicide may be functional behavior adaptations within a hostile and hopeless social context.” In other words, we need to know more about alcohol abuse and historical trauma. Eduardo Duran and Bonnie Duran go on to advocate a need for a “postcolonial history of alcohol.” ((The quotes are from Eduardo Duran and Bonnie Duran, Native American Postcolonial Psychology. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995) as cited by Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitakers, “Indians Are Naturally Predisposed to Alcoholism,” Myth #18, in Dunbar-Ortiz, 130-136.))

Parenthetically, the following year I raised funds at my Minnesota college for SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s civil rights activism in the South and even hitch-hiked to Louisiana in an attempt to get involved. At no point did I connect those actions with the historical and ongoing oppression of Indigenous peoples in my own backyard. Growing up on the Great Plains, I knew nothing about this actual history and like my peers was subjected to disingenuous, sanitized, elite-serving origin stories.

There’s Gold In Them Thar Hills!

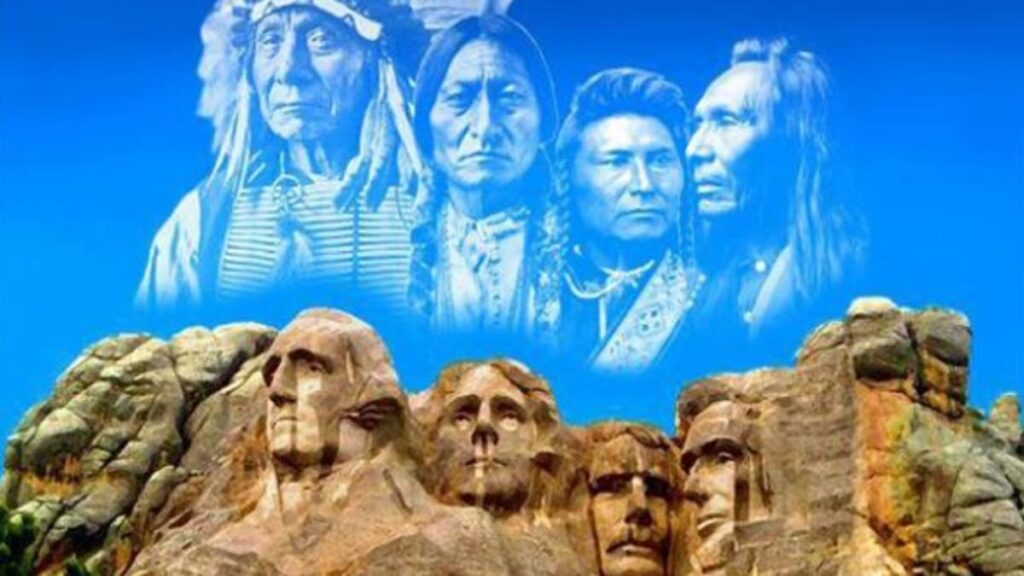

A microcosm that serves to encapsulate several points in this essay and is illustrative of the woeful state of my political awareness at the time is Mount Rushmore. Carved into the granite slope over the Black Hills of South Dakota. Mount Rushmore was a popular and almost obligatory destination for family car trips. Until only a few years ago, I was unaware that this “Shrine of Democracy,” this revered site of Americana, was known to the Lakota as Six Grandfathers Mountain. Its location was considered not only sacred religious ground but the apex of the universe for the Lakota people. After signing the 1968 Treaty of Laramie with the U.S. government, the Lakota obtained exclusive use of the Black Hills. Ten years later, when gold was discovered and thousands of miners rushed to the area, the government rescinded the treaty. On February 28, 1977, the federal government officially stole the land for the second time and began profiting from the gold, minerals and timber.

The following essential background, which like so much else, is egregiously ignored by historians and missing from the classroom, is as follows: In 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer to take his troops in the Black Hills and his official mission was to find the optimum site for a military post. Left out of the narrative is that Grant paid out of his own pocket for two prospectors to accompany Custer to follow up on rumors that the Black Hills was rich in gold. The first dispatch from a journalist on the expedition confirmed the rumors when he wrote: “From the grass roots down it was ‘pay dirt.” A “New El Dorado” had been discovered and Grant began scheming about how to renege on his earlier, solemn “Peace Policy” pledge toward the Indians.

Documents unearthed by diligent researchers at the Smithsonian reveal that in a closed meeting, Grant said, “The Lakotas must go or get whipped” which was a subterfuge to begin manufacturing complaints against the indigenous population. In the meantime, believing they would refuse to leave, a secret plan was hatched to launch a campaign against unsuspecting Indian villages. And in response to his insistent instigation, Grant’s Indian agents in the West sent back totally fabricated stories about the Indians not only being defiant and “hostile” but recommending that a thousand soldiers be dispatched to the Black Hills “to throw the ‘untamable’ Lakotas into subjugation. One unanticipated consequence was the Little Big Horn debacle but after the Indians had been subdued, Secretary of War J. Donald Cameron assured Congress and the nation that “the accidental discovery of gold” did not cause U.S. military operations in the Black Hills. On October 4, 1927, the sculptor Gutzon Borglum took on the Mount Rushmore carving project, in his words, as “a testament to American exceptionalism” and “a space for uncomplicated patriotism.” ((The entire sordid story is laid out in meticulous detail and by Peter Cozzens, “Ulysses S. Grant Launched an Illegal War Against the Plains Indians, Then Lied About It,” Smithsonian Magazine, November, 2016; Also, Amy McKeever, “The heartbreaking, controversial history of Mount Rushmore,” National Geographic, October 28, 2020. The sculptor’s previous project upon which he worked closely with the Ku Klux Klan, was a massive bas-relief at Stone Mountain, Georgia in which he memorialized Confederate leaders. )) Looking back, what if instead of presented with a totally fabricated history, a visit to Mount Rushmore could have been a lesson in critical thinking, a teaching moment?

Formal Miseducation

A closely related adjunct to the above, is that undergraduates at my Minnesota college were in a potentially privileged position to learn about the truth about these matters, and especially immigrants’ settlements and in our own Red River Valley, from a nationally acknowledged expert on the topic. A local farmer himself, Hiram Drache was a professor in the History Department, author of a dozen books and invited speaker for hundreds of talks around the country. Even after this long passage of time, I hoped I would recall at least one class lecture on the near annihilation of Native-Americans but none come to mind.

To check my unreliable memory, I went back and looked at Drache’s books and found only a few scant references to Indians including “Indian problems,” a single mention of the terrifying “Sioux outbreak” of 1862 and a military garrison being constructed “to watch the southern Minnesota Indians.” In what was arguably his well-known book (now in 12 printings) from 1964, the five stages of settlement, from rugged frontiersman to the frontier’s end with the arrival of urbanization I was unable to detect even a hint at the violent methods by which all the free, fertile land had been obtained. ((Hiram Drache, The Day of the Bonanza. (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1964), p.3. In his conclusion, Drache mentions that one of the truly memorable contributions of the settler era is that it served as a “dramatic basis for innumerable tales of greatness and folklore which are only matched by Paul Bunyan.” p. 220; The Challenge of the Prairie (Fargo: ND: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1970); Taming of the Wilderness: The Northern Boundary Country: 1910-1939. (Danville, Illinois: Interstate Publishers, 1992).))

In an effort to see if he’d made amends for his earlier professorial sins of omission, I looked over his 343-page book from 1992, titled Taming of the Wilderness, the focus of which was on the northern half of Minnesota. It was praised for its enlightened treatment of this “huge empty space” I was not surprised by the meticulous research and attention to the smallest detail. However, the only reference to Native Americans was about the Minnesota State Supreme Court ruling that Indians living on Federal property could not vote in a referendum on changes in the liquor laws. ((Hiram Drache, Taming of the Wilderness: The Northern Boundary Country: 1910-1939. (Danville: Illinois: Interstate Publishers, 1992). ))

We might also have learned from a bona fide expert that at the higher levels of officialdom, Territorial Governor, Alexander Ramsey’s wasn’t an outlier when he wrote to President Lincoln in 1862 and placed all the blame on the “savage” Indians: “This is not our war, it is a native war… More than five hundred whites have been murdered by the Indians.” Another individual who was emblematic of elite opinion and the rhetoric of extinction was the aforementioned Henry Hastings Sibley from the Dakota War of 1862.

I recall Sibley’s name being memorialized by counties, parks, streets and schools across the state including my traveling on the Sibley Memorial Highway near the Twin Cities. As with so much else about local history, I was totally ignorant of the fact that Sibley, Minnesota’s first Governor, was also Ethnic Cleanser-in-Chief on land that he’d once characterized as “pristine.” Col. Sibley commanded 1,200 troops U.S. troops during his “punitive expeditions” and in 1862, he wrote the following to Alexander Ramsey about Indians: “My heart is steeled against them, and if I have the means, and can catch them, I will sweep them with the besom of death.”

Fittingly, after being mustered out of the military, Sibley served as president of the Minnesota Chamber of Commerce, on the boards of railroads, banks and was a regent of the University of Minnesota. Princeton University bestowed an honorary doctorate on Sibley in 1888. It’s encouraging that, in 2020, under pressure from Native Americans and citizens who’d previously known only a sanitized version of his past, Sibley’s name was erased from a high school in the Twin Cities and changed to Two Rivers High School. A quarter of the current students and many previous graduates signed a petition supporting the name change.

On a related note, after years of fierce wrangling and court reversals, the name Lake Calhoun in Minneapolis was restored to its original Lakota name, Bde Maka Ska. It had been named to honor U.S. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, prominent slave owner and author of the Indian Removal Act. In a split decision in 2021, the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled in favor of the change and shortly thereafter, shopping centers, public squares, entire neighborhoods, cycle shops, and gyms quickly shed the name “Calhoun.” The speed of change was undoubtedly expedited by the new awareness following George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis and the Black Lives Matter movement.

A final example, although not specifically about Minnesota and the Dakotas, concerns my miseducation about Lt. Col. Kit Carson, the iconic frontier hero of the Old West. As a child I had a Kit Carson cap pistol, wanted to be Carson when playing Cowboys and Indians and in the early 1950s I faithfully watched The Adventures of Kit Carson every day after school. Undoubtedly, this was also true for kids in Colorado where I later did my graduate work from 1968-1973 and became familiar with the 14,000-foot Mount Kit Carson, one of the “Elevens” revered by climbers in the state.

Yet, even though then in my mid 20s, I confess to being unaware of the fact that Carson was a war criminal who spearheaded the U.S. government’s genocidal campaign against the Navahos. In 1862-63, after some “Indian trouble” — translated: they refused to accept confinement on a reservation — Col. Carson led a brutal campaign against the Navajos, burning their crops, destroying their villages, and slaughtering their livestock. He then proceeded to round up 8,000 Navajo men, women and children and forced them on what became known as the “Long Walk” of 300 miles from Arizona to the Bosque Redondo Reservation in New Mexico, a trek taking over two months. In 2011, by a 10-0 vote, a federal agency denied a request to rename the mountain. However, an encouraging development occurred last year when the Kit Carson elementary school in Las Vegas changed its name.

The annual Kit Carson Mountain Men Rendezvous goes on in Kit Carson, Colorado where participants are strongly encouraged to wear “primitive” clothing as they participate in gun-shooting centered festivities. And if one is in California, they can relax at the “rustically elegant” Kit Carson Lodge in the Sierra Nevada mountains, a resort that dates back 95 years. Yet another available option for “pioneer fun” and an authentic legend of the Old West experience is the five-day Kit Carson Wagon Train re-enactment. Finally, on the educational site “Kids-n-Cowboys” we learn that Kit Carson helped make “the great American expansion possible.”

Socialists Among The Settlers?

At this point, I admit that before starting this undertaking I assumed I’d come across a few heroes, some radical dissenters who at least raised the matter of indigenous dispossession even as they gained from it? We know that by 1920, some 50,000 immigrants returned to Norway. Many had sent money orders to the old country for the eventual purchase of land. It’s not inconceivable that some of them also returned out of disgust with what they learned on the American frontier but, in general, the record is silent. In terms of those who remained, two of the most instructive, albeit troubling cases I came across were Marcus Thrane, a radical Midwest socialist and GAA PAAS (Press Forward), the leading Norwegian-language socialist newspaper of the time.

Marcus Thrane admired the Paris Commune, organized the first rural workers’ union in Norway with some 30,000 members, edited it’s newspaper and framed union demands that included universal suffrage and land reform. Sensing a threat from below, on July 7, 1851, Thrane and several other leaders were arrested in a large-scale police action that easily crushed any incipient revolt. Thrane and 132 other union members were arrested and sent to prison in 1855. After serving eight years, Thrane resumed his organizing efforts but with little success and, frustrated, he emigrated to the United States in 1862.

Upon arrival, he immediately resumed his radical politics among Norwegian immigrants including the editorship of two socialist newspapers, public speaking and writing populist plays, including some satirizing the Lutheran Church. The latter prompted church leaders to condemn his socialist ideas further diminishing his radical project. After once having seen so much potential in his adopted country and having urged others to seek a new life there, Thorne became thoroughly disenchanted with American society and its government. He was prescient in predicting that the United States would never be “The Shining City on a Hill,” or the “Citadel of Democracy” admired across the world. Thrane died in Eau Claire, Wisconsin in 1890 and later, the Norwegian Labor Party referred to him as one of its founding fathers and today monument honoring him sits in his hometown of Drammen, Norway. ((Anders Bo Rasmussen, “On Liberty and Equality: Race and Reconstruction Among Scandinavian Immigrants, 1864-1858,” in Jana Sverljuk.))

In retrospect, if anyone should have recognized that the Indian was, in legal scholar Felix Cohen’s words “the miner’s canary” in flagging the sham of American democracy it would have been Marcus Thrane. However, I searched the record in vain for even a passing reference to this vexing indictment of “liberty and equality for all” and found only a glaring moral blind spot. However, can I say with conviction that I would have acted differently?

The second example is GAA PAA (Press Forward) the prominent Norwegian-language socialist newspaper in Minnesota. In an important article, the noted Scandinavian studies expert Odd Lovoll described GAA PAA thusly: “The collective life of the Norwegian-American community can be viewed through the prism of this socialist organ” and the paper’s editorial position was that Norwegian farmers were the natural allies of the working class “…in the battle to defeat capitalism.” ((Terje Leiren, “Lost Utopia? The Changing Image of America in the Writing of Marcus Thrane,” Scandinavian Studies, Vol. 60, No.4; and by the same author, Selected Plays of Marcus Thrane, New Directions in Scandinavian Studies. The University of Washington, 2008. )) All the more striking to find that any concern for the indigenous population never surfaced in any issue of the paper, perhaps early evidence of colonized minds, including socialist ones.

Parenthetically, I should mention that growing up in North Dakota I was always proud of the state’s history of agrarian radicalism which began in the 1880s. In 1918, the Nonpartisan League (NPL) won all three branches of government and immediately enacted its program of “state socialism,” easily the most progressive in the entire country. Concurrently, voices across the board cried out against farmers and laborers being exploited by bankers, Twin City grain merchants and the railroads. I mention this because at no point did it occur to me that Indian dispossession was ever mentioned.

What Did They Know And What Does It Matter?

Here we return to the question of whether the vast majority of these first Norwegian-Americans were cognizant of the formal and informal structures, the nefarious mechanisms involved in colonialism, the broken treaties, officially sanctioned bloodshed, myriad injustices, toxic ideology, and the economic motives of rapacious empire builders? If they were not, is it necessary to parse the meaning of “settlers” and perhaps reconfigure their role as being closer to self-interested pawns manipulated by others?

For me, the answer to questions regarding the ordinary immigrant’s self-perception and view of the Indigenes remains maddeningly problematic. I recently came across sociologist Karen V. Hanson’s inestimably valuable book, Encounter On The Great Plains, the focus of which is Scandinavian immigrants to North Dakota from 1890-1930. These settlers included some of her ancestors who’d settled on Indian Reservation land near Devil’s Lake and although their circumstances were not identical, her take on them is as follows:

Norwegians like my great-grandmother did not come to be settler colonialists or to usurp the place of others. They deeply resented having been colonized by Danes and Swedes and could not conceive of themselves as occupying an oppressive position in a foreign country. As newcomers, immigrants were searching desperately for a place to make a home: they were steered onto the reservation enterprise by forces largely beyond their control and outside the kin. With vivid memories of the suffering endured in Norway and Sweden and the sacrifices made during migration, they judged themselves and their descendants worthy of the land… They dwelt on the present and future as land takers often do, and they rarely probed the past or questioned laws that privileged them and disadvantaged others. ((Odd Lovell, “GAA. PAA: A Scandinavian Voice of Dissent,” Minnesota History, Fall 1990, pp. 87-89.))

As I began delving further into the history I found contrary opinions among elite opinion shapers, those farther up the social hierarchy. For the area where my grandparents settled, I came across this official history of Stearns County, Minnesota which contained a telling excerpt:

What title did the Indian have to the land? Why should the Indian be considered the owner of the land? Just because he occupied it first? One would judge that by the highest ethical standards the superior civilization has the right to the land.

And then, this statement about the meager sums frequently paid for the land:

The Indian, this simple child of nature has been given a fortune which he could not care for… If the Indian had used wisely what our government has paid them, every man, woman and child of the race today would be well-to-do. ((William Bell Mitchell, History of Stearns County, Minnesota, 1915.))

We also have Anders Bo Rasmussen’s meticulous, indispensable research which strongly suggests that the Scandinavian immigrant elite, including opinion shapers like newspaper editors, historians and Civil War officers “transplanted Old World perceptions of class and race to the New World, which, in turn, helped to inform how Scandinavians immigrants confronted the post-war reality of slavery’s abolition.” The very first edition of the Norwegian-language newspaper, The Fatherland, described the new American republic as a “glorious institution in accordance with human and divine law” that was created “on liberty and equality.” Articles like these were widely shared in Norway, especially in rural areas.

Rasmussen makes a compelling case that many Norwegian immigrants arrived with preconceived perceptions of white men “at the top of a racial hierarchy,” who deserved a higher rung on the “agricultural aristocratic ladder.” They resisted Black people having equal opportunities in the Northern labor market and believed “whiteness separated them from what they described as a “lower class of people.” ((Email to author, July 27, 2021.)) Soon, it was no contest between egalitarian ideals and economic opportunities for whites. This view is reinforced by Terje Mikael Hasle Joranger, Curator of the Norwegian Emigrant Museum in Oslo and a widely acknowledged expert on the subject. In his generous response to my inquiry, he wrote:

In my research I have come across very few references to America in letters, for example, showing any sign of remorse or thoughts connected to land-taking seized in an improper manner from indigenes. There is a great silence connected to references to the indigenous population among Norwegian immigrants in letters, diaries, and reminiscences. References to land in letters are to a large extent tied to concrete mention of land prices of government land, to heads of cattle, and to the growth of various crops.” Joranger continues that the letters largely reflected a concern of practical matters and thinking about how to improve his lot. These individuals “were not looking back in order to judge any harm done to the indigenous settlers. ((Terji Mikael Hasle Joranger, “The Creation of a Norwegian-American Identity in the USA,” Journal of Migration History 5 (2019) p. 489-511.))

A related explanation comes from Hanson’s aforementioned research. Drawing on 130 oral interviews and fifteen years of archival research, Hanson concludes that these early immigrants were not consciously “settler colonialists” but were, nevertheless indispensable to the colonialist state’s imperial expansionist project. In short, they unwittingly solved the government’s “Indian problem.” Indeed, by 1929, Scandinavians owned more reservation land than the Lakotas.

Hanson’s search was prompted, in part, by trying to come to terms with her “troubled conscience” over a past that privileged her at the expense of others. Her observation about Scandinavians surely applies to virtually everyone of immigrant descent in the United States: “Scandinavians past and present have eluded the thorny past by misrepresenting it or by living uncomfortably with their personal or ancestral history.” ((Karen V. Hanson, Encounter of the Great Plains (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) p. 238.)) Given only those two choices, my sense is that misrepresentation still prevails, leavened with heavy doses of denial to reduce the discomfort level. However, this essay suggests that filling a gaping lacuna of ignorance with the actual facts regarding the past might open a third choice and I now turn to sketching out more of that context.

Demythologizing History And Decolonizing Our Minds

Consistent with the abiding concern of another analyst looking into this past, my motive has been “…to understand the ongoing processes that have shaped our world… The predicaments in which we find ourselves derive in part from the history of colonial conquest, slavery, imperial warfare, and the inequalities that emerged from this history we might discern the scope, force, direction and likelihood of the change ahead — and be guided by the example of our ancestors. ((Brad Evans, Interview with Vincent Brown, “Histories of Violence: Violence, Power and Privilege,” Los Angeles Review of Books, March 1, 2021.))

Put another way, believing the “personal is political,” I began this exploration with a combination of personal and political activist motives. On the one hand, I was uncomfortable with the lacuna about my ancestral background and wanted some resolution — wherever that might lead. On the other, would an objective understanding contribute to greater clarity and utility regarding my existing political commitments? At this point, after substantially enlarging the scope of my inquiry, it feels as if I’ve tentatively arrived at a productive intersection of the two concerns.

By now it’s apparent to the reader that I’m ambivalent about portraying my Norwegian-American ancestors with the broad, often pejorative brush of “settler colonialist” as the last word on the subject. My sense is that there remains a larger, more politically propitious perspective that’s routinely overlooked or avoided. At the same time, I’ve been sensitive to Gerald Horne’s accusation that many hypocritical analysts have avoided giving sufficient attention to his assertion that after being “deputized,” European settlers became accessories in victimizing the indigenous. ((Gerald Horne, “Against Left-Wing White Nationalism (Organizing Upgrade).”))

Trying to assess degrees of moral culpability is both unavoidable and necessary in terms of advancing our political understanding with an eye on the future. For radicals like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, the capitalist state bears the major responsibility whereas for many conventional historians, settler colonialism operated from the bottom up. For example, in one recent book which was fulsomely praised in establishment circles and was a National Book Award Finalist, the author makes much of newcomers in the 1830s being enthusiastic exterminators and being “too avaricious” to allow indigenous people to remain. And he almost offhandedly contends that a consistent application of the Republic’s “radical revolutionary values” could have avoided this outcome altogether. ((Claudio Saunt, Unworthy Republic (New York: W.W. Norton, 2020). )) Again, I could not find a negative word about “capitalism” in this 396-page tome and perhaps needless to mention, mythical feel-good origin myths about the country are simply taken for granted. Most historians simply evade, dismiss or gloss over the entire matter.

Where so many mainstream writers miss the mark is that whereas dispossession was a zero-sum game, these would-be settlers, mostly peasants, were fleeing feudalism at home. It may seem a distinction without a difference, but there is no evidence suggesting they arrived here with the conscious intent of exploiting the indigenous population for economic gain. Their complicity, if that’s the proper word, is that they functioned as foot soldiers to the unceasing capitalist logic of elimination, in service to a merciless capitalist logic from which they initially benefited. Horne argues that for these settler recruits, land was their “combat pay” for serving as white invaders. Again, another reading of this period suggests that, indeed, a cross-class convergence of interests occurred but only one partner was dimly aware, if that, of being used as an indispensable tool in establishing the property state for private capital accumulation while also serving elite interests in offsetting the vast number of slaves in the country, the “enemy within” feared by the existing polity. If so, I don’t believe it’s exonerating the settlers to recalibrate the term “settler colonialist” when applied to them. Building on earlier discussion, I’m suggesting that it’s impossible to arrive at a meaningful answer to my overall inquiry or draw any useful lessons without engaging the work of some of the revisionist critics who have convincingly undermined comfortable American origin myths about liberty and equality.

Regrettably, many people, including most scholars and some of the self-identified left insist on portraying the American Revolution as besieged patriotic colonists, forthrightly standing up against British economic tyranny, a glorious confirmation of U.S. exceptionalism. One of countless examples is Joseph J. Ellis, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his book, Founding Fathers. Ellis recounts that “No less an authority than George Washington observed at the end of that any historian who managed to write an accurate account of the war for independence would be accused of writing fiction.” ((Joseph J. Ellis, The Cause: The American Revolution and Its Discontents, 1773-1783. (New York: Liveright, 2021), No page. According to pre-publication reviews, the book attempts to shed light on some unsung heroes of the period; Joseph J. Ellis, Band of Brothers (New York: Random House, 2000); Another recent, celebratory example is Mike Duncan, Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette. (New York: Public Affairs, 2021).)) Washington was not wrong about the fictional accounts, only just how far they would depart from the actual truth.

Ellis’s own fawning account of Washington would qualify as he extolled the countless virtues of the “brothers” as men who would win the title for “The Greatest Generation” hands down. According to Ellis and countless other myth-making historians, the great activity of this revolutionary generation was their devotion to popular sovereignty and their “common sense of purpose. ((Book Browse, An Interview with Joseph J. Ellis (nd). In 1779, this “common purpose” included Washington’s explicit order for the genocidal Sullivan expedition against the Iroquois nation in upstate New York. According to plan, more than 40 villages were burned to the ground and all crops and winter provisions were destroyed. Their morale totally broken, those not killed or captured fled to Canada. The Haudenosaunee named the first president, the “Town Destroyer.”)) The transparent truth is that the American Revolution was “[T]he first chapter in an inter-imperial war between Great Britain and its dissident elites in North America” and also the advent of American imperial warfare.” ((Historian William Hogeland, interviewed by Jonah Waters, “Not Our Independence Day,” Jacobin, 07/04/2006. 48.))

We know that as early as 1760, less than five hundred men in just five colonial cities controlled most of the shipping, banking, mining, manufacturing and commerce on the eastern seaboard. In truth, our venerable Founding Fathers were slave owners, wealthy men who wanted a system that would further their interests. ((Michael Parenti, Democracy for the Few, Ninth Edition (Boston: Wadsworth, 2011) p.11.)) Founding Father Alexander Hamilton (subject of a recent, disingenuous Broadway musical) bought and sold slaves for his wife’s family, owned slaves himself and spoke about Indigenous peoples as aggressive “savages.” In her new book, Dunbar-Ortiz includes Stanford law professor and historian Gregory Ablavsky’s observation that Hamilton and his fellow federalists resolved to “solve the problem of Indian affairs by committing the federal state to empowering, not restraining the inexorable westward tide.” ((Gregory Ablavsky, “The Savage Constitution,” Duke Law Journal, 63, No.5 (February 2014): pp. 999-1000, as cited by Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz, Not ‘A Nation of Immigrants’ Boston: Beacon Press, 2021) p. 40.))

Many of the Founders, including George Washington, were land speculators and long before King George III issued the Proclamation of 1763, forbidding settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains, these men had begun making claims on this native land. They were eager to push forward into Indian territory. Jumping ahead a bit and in what was already a fait accompli, in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the British agreed to recognize American independence all the way to the Mississippi River.

These wealthy slave owners wanted a system that furthered their interests and fifty-six of these noteworthy members of the propertied class later signed the Declaration of Independence. All of these famous “patriots” had only contempt for actual democracy, feared it and recoiled from it. As one American historian corrects the historical record, “The American state, even in its earliest incarnations, was more concerned with limiting popular democracy than securing and expanding it.” ((Hogeland.))

Here it’s imperative to remember that Europeans did not think of themselves as “white people” until it became an arbitrary social construction and to the extent that my ancestors did it was a relatively recent phenomenon. In earlier times, people saw themselves as members of a clan, tribe, religion or geographic area. And when the transformation began, its contingency was tied to its service to England and later the United States’ exploitation of “the other,” including Blacks and Indians. Gerald Horne adroitly depicts the latter transformation with only a trace of hyperbole when he writes: