REE’s — Rare Earth Elements.

We’re all connected to the deep sea. There is no line in the ocean that says to us, ‘below this, nothing matters.’ The ocean is all connected. It’s the largest livable habitat on the planet.

— Astrid Leitner, Oregon State U assistant professor.

The interview HERE, to be aired, in 2026, KYAQ.Org (Finding Fringe — Voices from the Edge) covers, well, the part we do not see, for the most part, at the bottom of the sea:

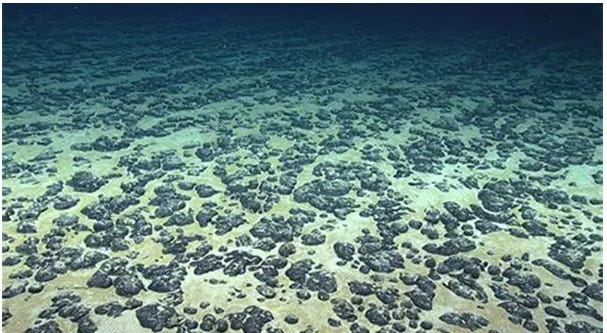

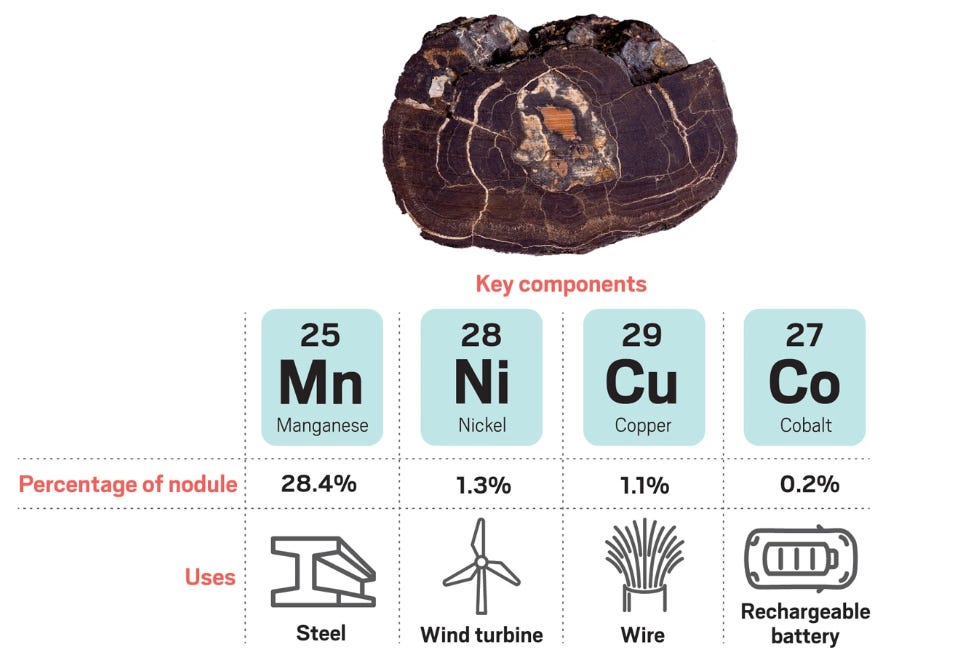

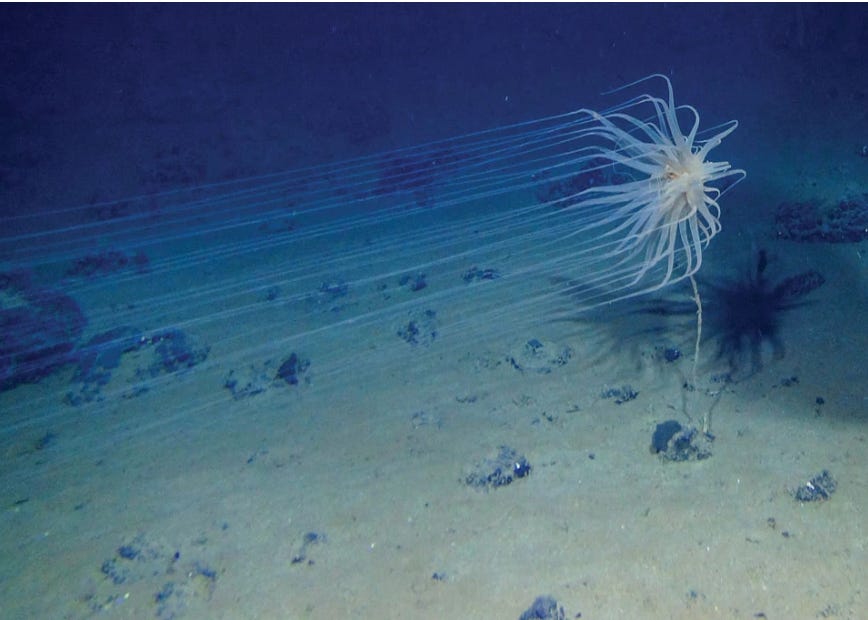

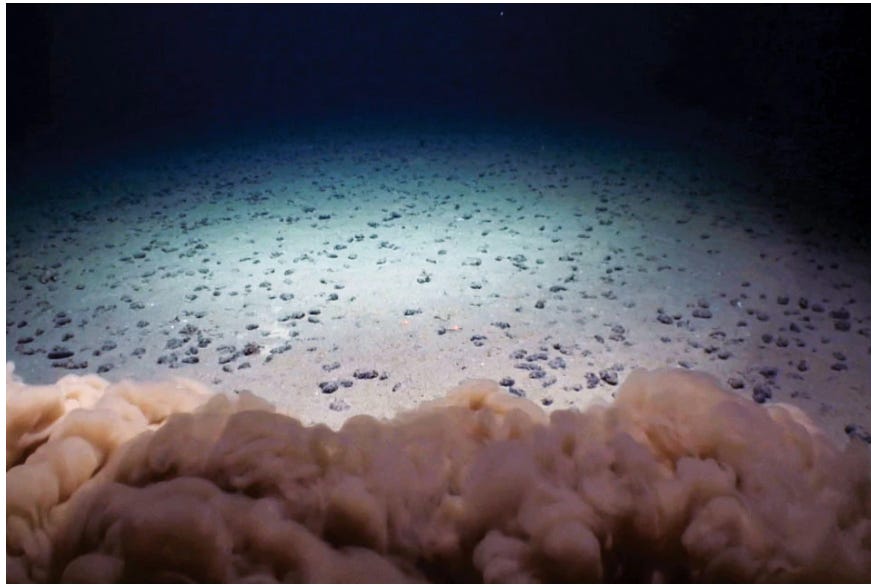

…formed over millions of years from falling debris like shark’s teeth or fish bones—acted as nuclei to gather trace minerals. The estimate is that the nodules grow about one millimeter every thousand years and, in some areas of the seabed, there are billions of these potato-sized rocks, each one teeming with minute marine organisms

This is Astrid’s work:

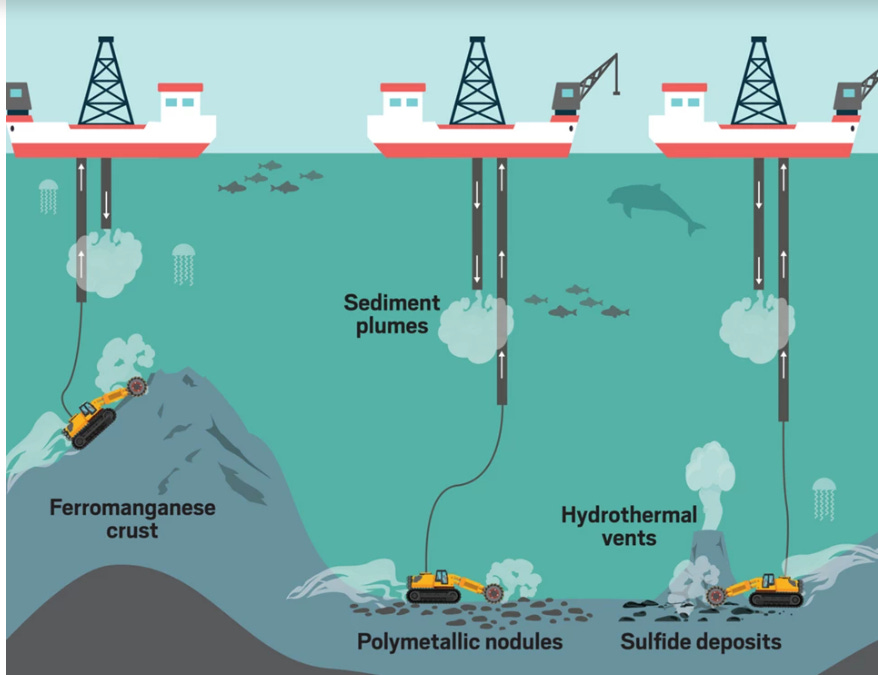

How will it impact the already diminished populations of phytoplankton which provide up to 70% of the oxygen in the atmosphere? How will it impact the already diminished populations of krill, the foundation of the food pyramid in the sea? How will deep sea mining influence the climate, the movement of currents, and the migration and viability of sea life? The industry has not answered these questions because there is no answer that they will acknowledge—because such answers will expose them as harbingers of global destruction.

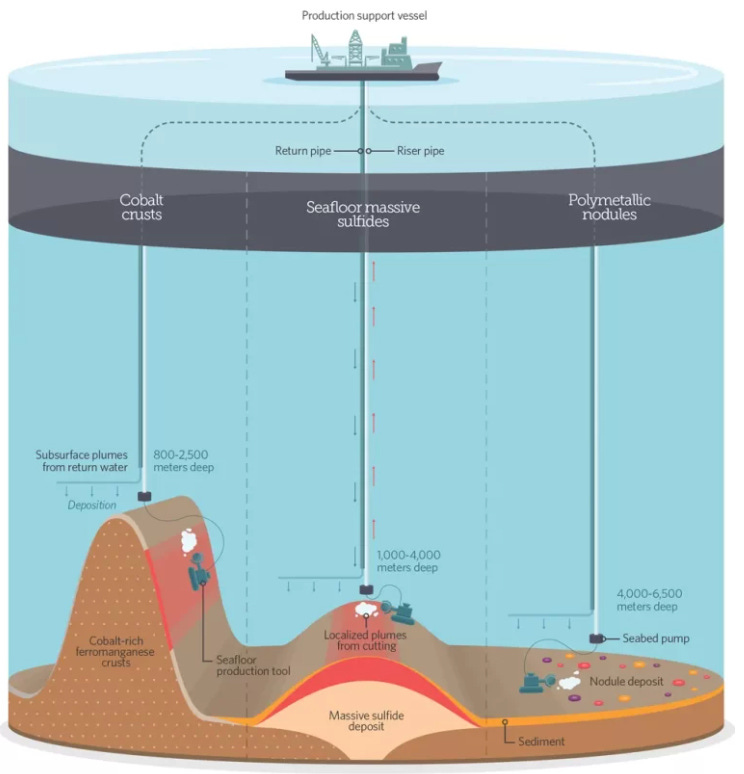

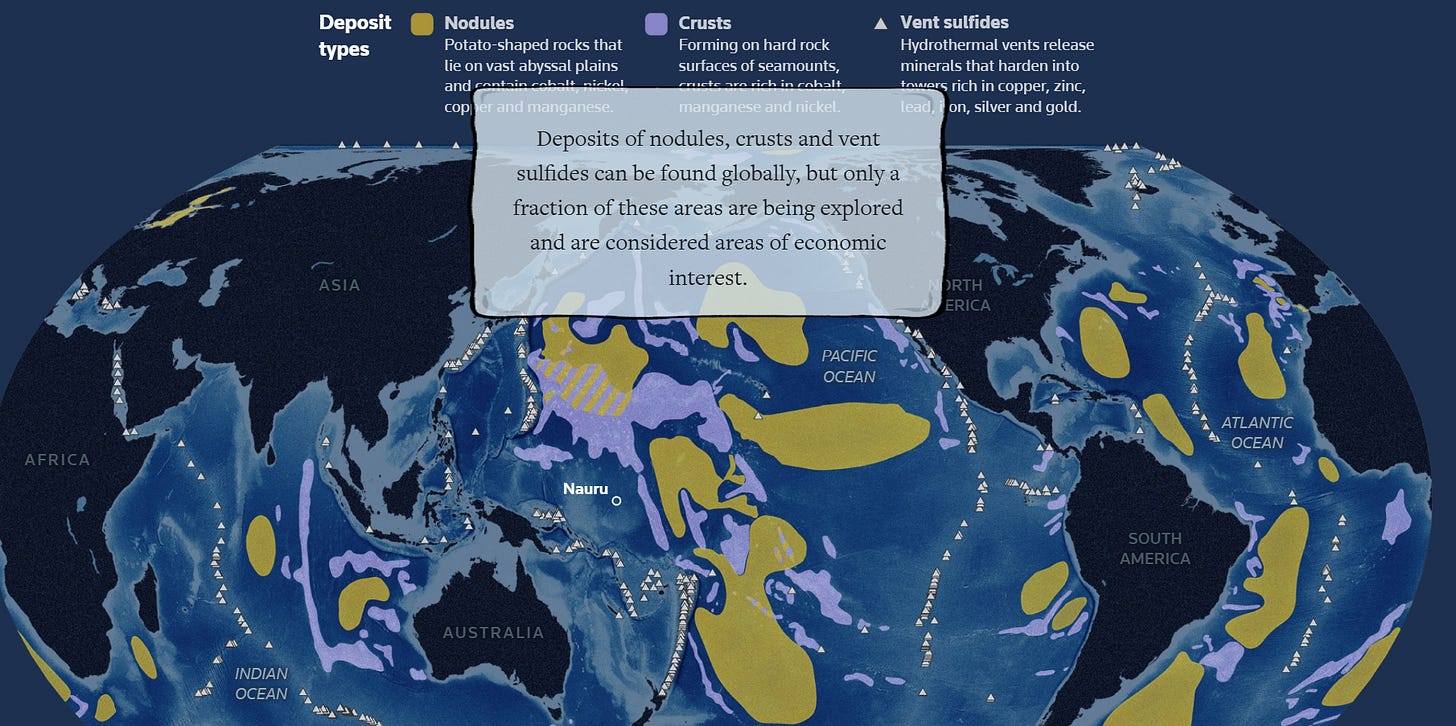

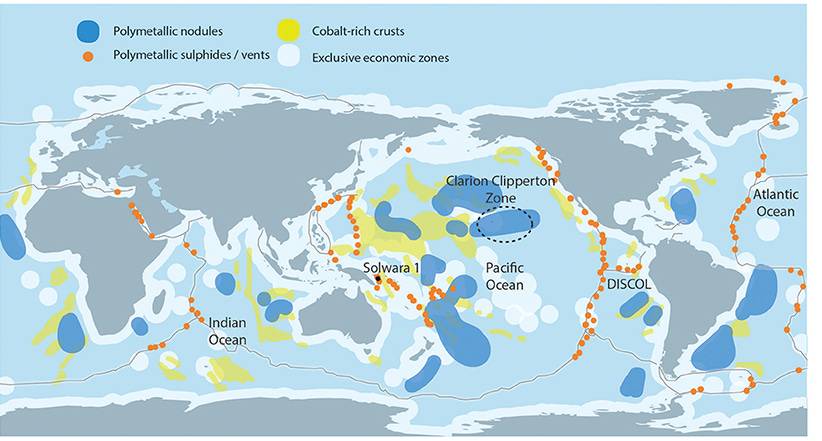

Since 2001, the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an intergovernmental body in charge of regulating deep-sea mining in waters beyond national jurisdictions, has granted 31 exploratory licenses to private companies and governmental agencies. The organization is unlikely to approve commercial mining applications until its 36-member council reaches consensus on rules regarding exploitation and the environment. Member states have set a 2025 timeline to finalize and adopt the regulations.

Read more here: The promise and risks of deep-sea mining

Astrid Leitner completed two bachelors degrees at the University of California at Santa Cruz in 2012. She has one degree in Marine Biology and another degree in Earth and Planetary Sciences. During her undergraduate career she focused mainly on coastal ecology, working for the Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans (PISCO). Astrid began her career working in the intertidal on a barnacle recruitment project. Later on, she began to work as an AAUS scientific diver in the California Kelp Forests studying the impacts of local, small-scale physical processes on the rockfish community.

Additionally, she spent one semester at STARESO (Station de Recherches Sous-marines et Oceanographiques) in Corsica, France where she studied factors influencing schools of Chromis, the Mediterranean damselfish. Astrid also completed an NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program at Oregon State University where she worked on her first deep sea project. While in Oregon, she worked on the fish community in Astoria Canyon, a large submarine canyon beginning at the mouth of the Columbia River. For this project Astrid analyzed Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) footage from depths ranging from 100 to 1400 meters.

As a part of her research, Leitner discovered the largest aggregation of fish ever documented at abyssal depths of 10,000 to 20,000 feet. She also recently discovered a distinct midwater boundary community along the wall of the Monterey Canyon. In addition to her role as an oceanographer, Leitner is a dedicated advocate and mentor for women in science.

“Her subsequent work in graduate school at University of Hawaii and as a postdoctoral fellow at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute helped her hone her focus on the effects of steep and dramatic undersea features on deep-sea community ecology. Leitner’s work asks, what species use various abrupt deep-sea habitats? What are they doing in these habitats? How do the observed species interact with each other? How does community structure change over space and time? (Astrid Leitner shines light on the deep, dark sea.” — By Nancy Steinberg)

Recently, a team led by researchers at the Natural History Museum in London identified 5,000 new animal species from an untouched area of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (Curr. Biol. 2023, DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.052).

“And there’s millions, possibly tens of millions of species in the deep sea still to be described,” Travis Washburn, an ecologist who worked with the Geological Survey of Japan to study impacts of seabed mining tests, says. “Without knowing what’s down there, scientists can’t understand mining’s full impact.”

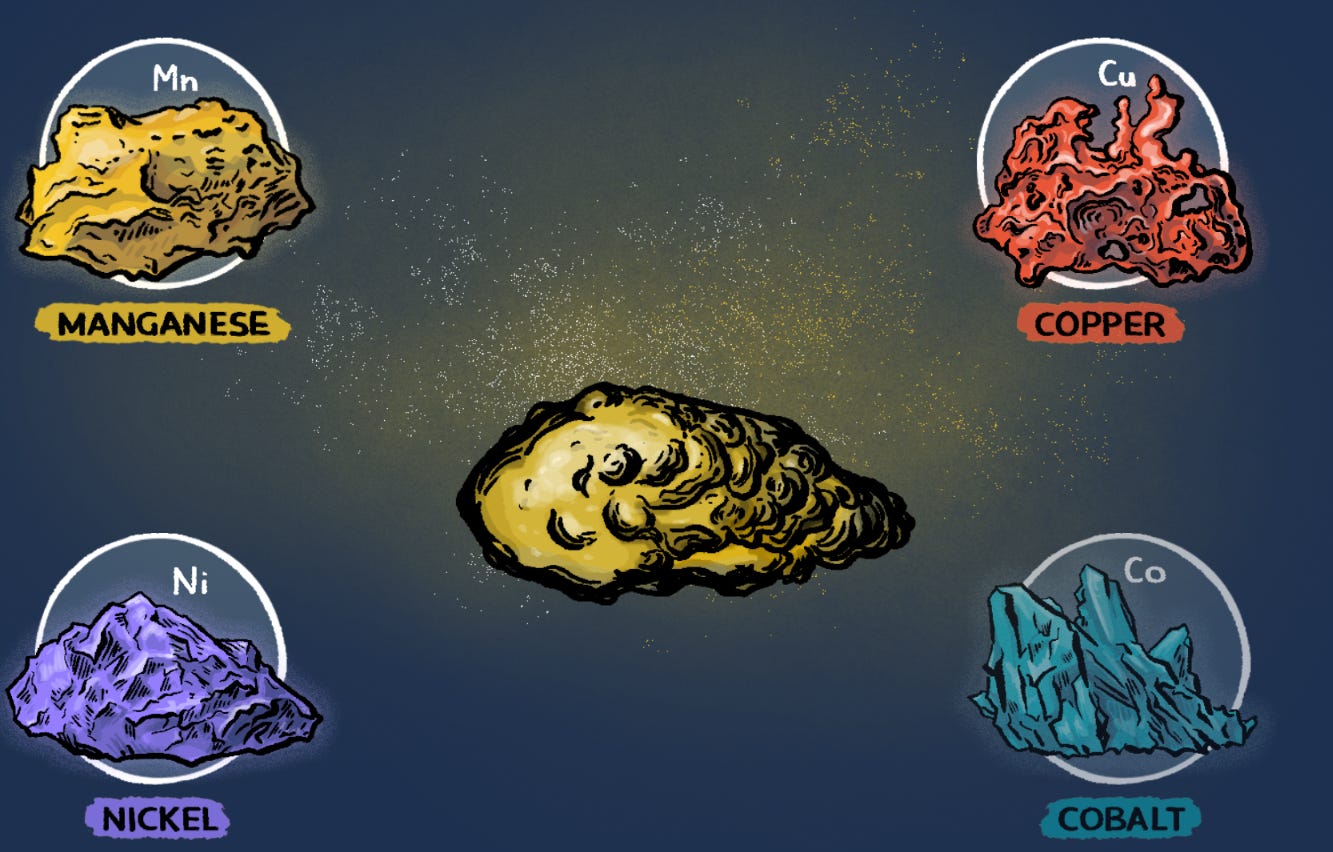

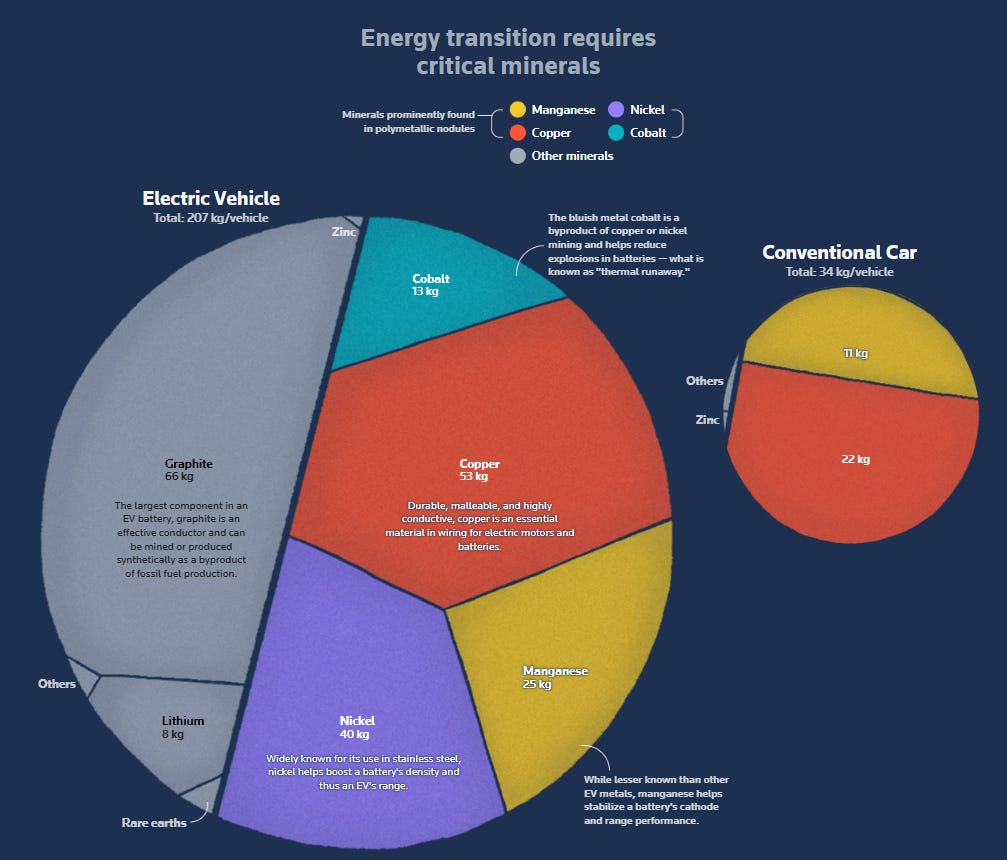

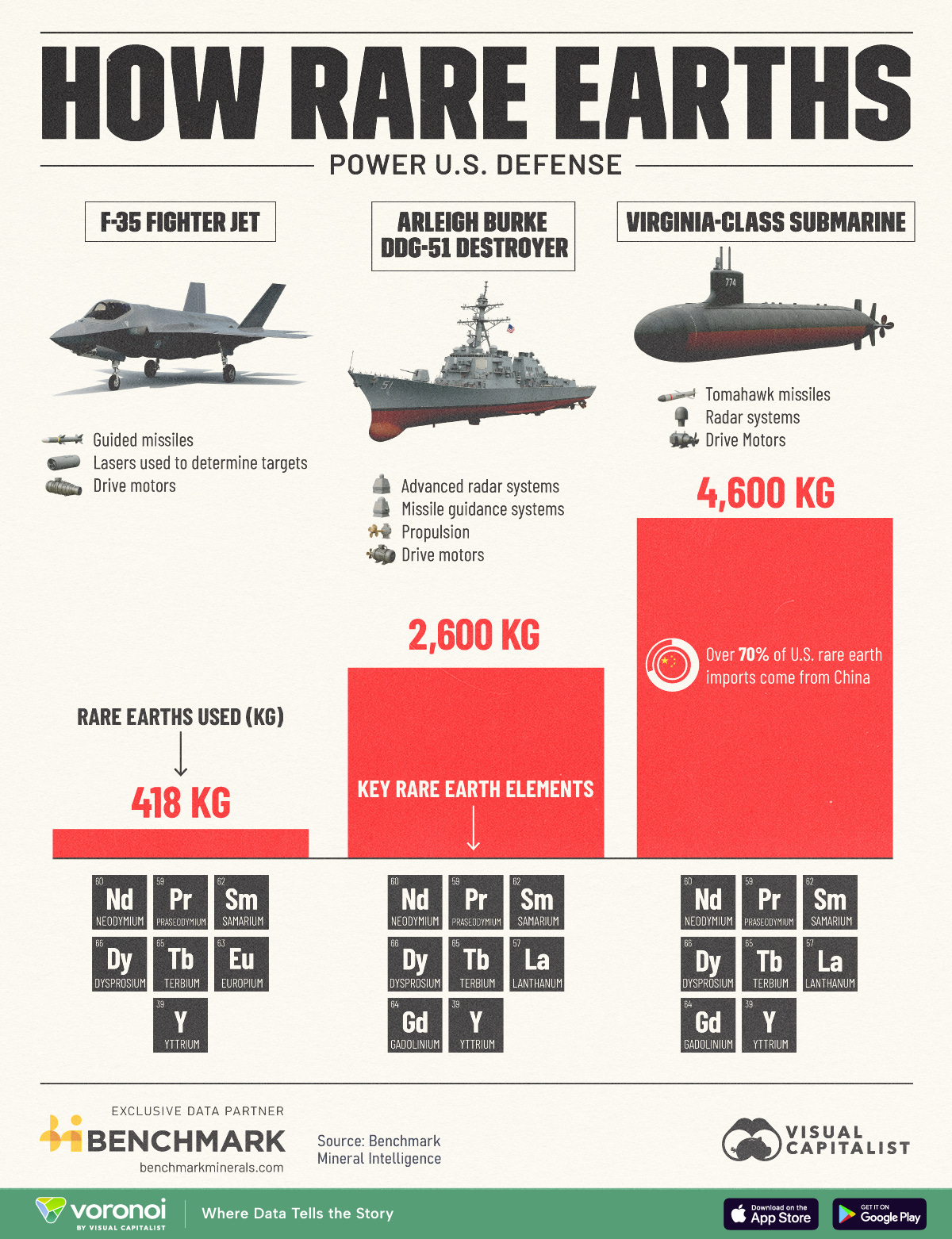

…copper, cobalt, nickel, zinc, silver, gold… Strategic Metals! War War War.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” ― I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked

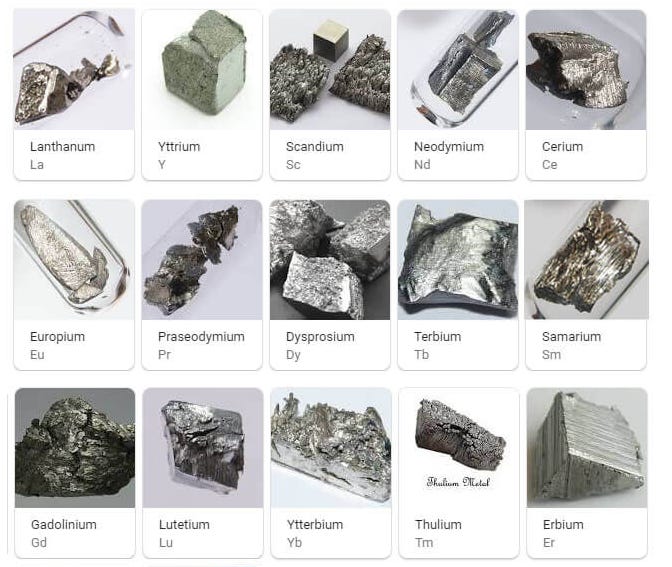

Rare metals

Rare metals are metals having a low average abundance and/or availability in the Earth’s crust (i.e. the capacity to concentrate in deposits). This is the case, for example, for indium, cobalt and antimony. Rare earths comprise a group of fifteen metals (the lanthanides) which form an integral part of the earth’s rare metals. They are commonly associated with yttrium and scandium. Their unique properties (lightness, strength, energy storage, thermal resistance, magnetic and optical properties, etc.) make them the elements of choice in a range of technology fields, ranging from defence to digital and energy transition sectors (e.g. permanent magnets, batteries, catalytic systems, etc.). Despite their name, the rare earths are not in fact that rare. However, their deposits – in other words, naturally-occurring concentrations that are economically exploitable – are typically not found in abundance.

Strategic metals

A metal is strategic if it is essential to a State’s economic policy (security, defence, energy policy, etc.). A metal may also be considered strategic for a particular company or industry (e.g. aerospace, defence, automotive, electronics & ICT, renewable energies, nuclear, etc.).

Critical metals

A metal is deemed critical if difficulties with the metal’s supply could have negative industrial or economic impacts. In most international studies the criticality of a metal (as of any mineral) is judged on two criteria: supply-side risk (geological, technical, geographical, economic, geopolitical), and economic importance which reflects the vulnerability of the economy to potential shortage or supply interruption creating a surge in prices. According to Raphaël Danino-Perraud, “In short, critical metals are metals associated with supply chain pressures, in terms of both supply and demand.” For the US National Research Council and the European Commission, a metal or mineral is critical when it is “both essential in use and potentially subject to supply constraints.”

This is what Astrid and I talked about: have a listen.

[A marine organism in the genus Relicanthus is attached to a dead sponge stalk tethered to a nodule.]

[While collecting nodules from the seabed, mining vehicles create sediment plumes that can harm ocean life.]

+—+

Rare Earths in the AI Era: How Data Centers Are Driving Demand for Forgotten Metals — Rare earth elements (REEs) consist of 17 metallic elements with similar chemical traits. This group includes the 15 lanthanides, plus scandium and yttrium. These elements aren’t truly “rare” regarding their presence in the Earth’s crust. However, they are typically scattered rather than gathered in deposits that are easy to mine profitably. This spread-out nature complicates their extraction and purification. Despite their name suggesting scarcity, rare earths are vital to modern tech. Their unique physical and chemical features drive their importance.

Here are some of Astrid’s publications, co-authored, and such.

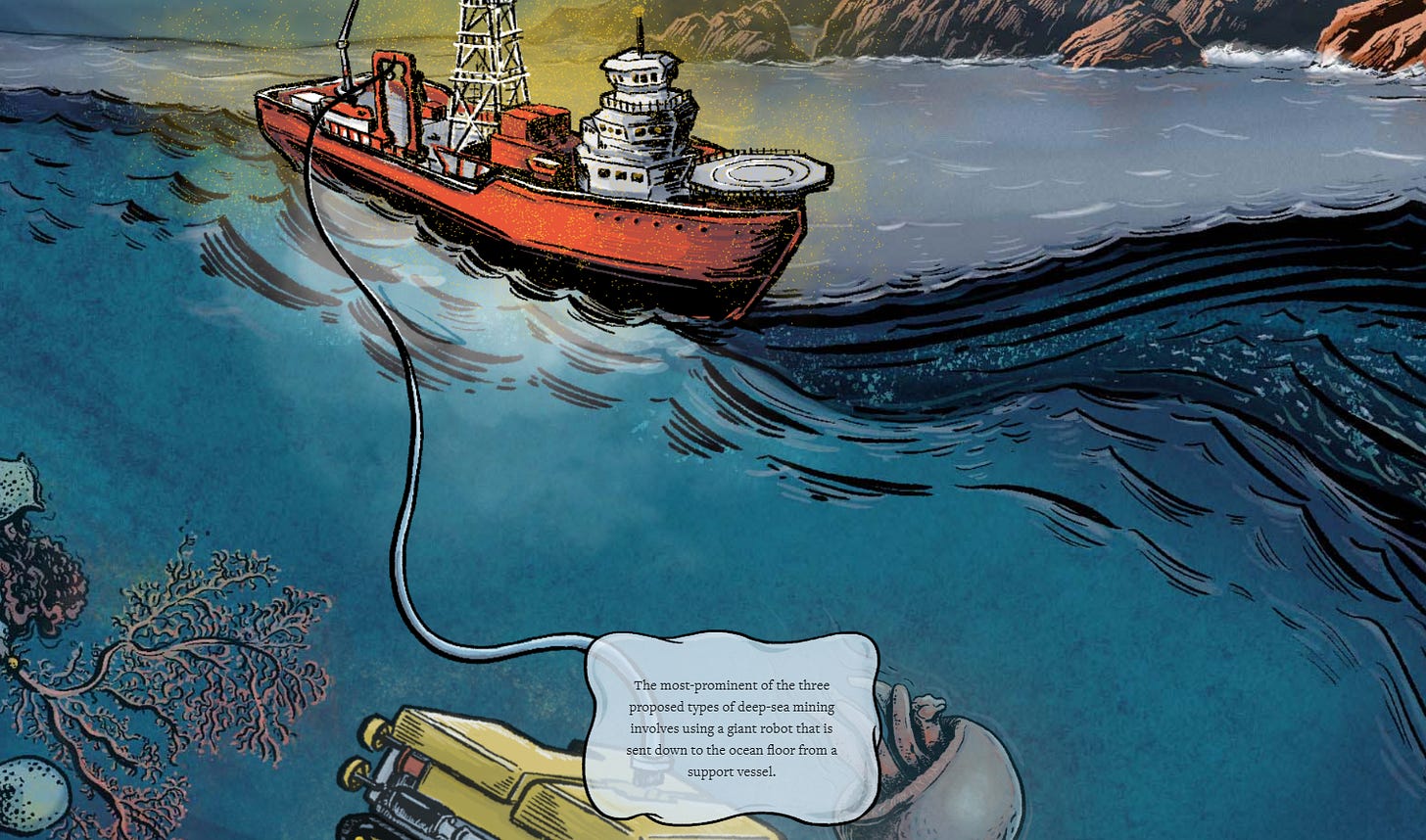

We got into her research, the power of economics driving this dirty industry, and the various laws of the open sea and the laws around deep sea mining, those written, those proposed, those not on the books.

But this is the empire of pain, dirt, pollution, lies, terror, and as we know, Trump is manipulated by Big Tech, MIC, and billionaires. We will pay for the mining, the costs, the external damage, costs, to us, to the sea, and even pay for the metal and mining companies going belly up.

[A Greenpeace activist holds a banner during a protest near a deep-sea mining vessel in Mexico, on September 27, 2023]

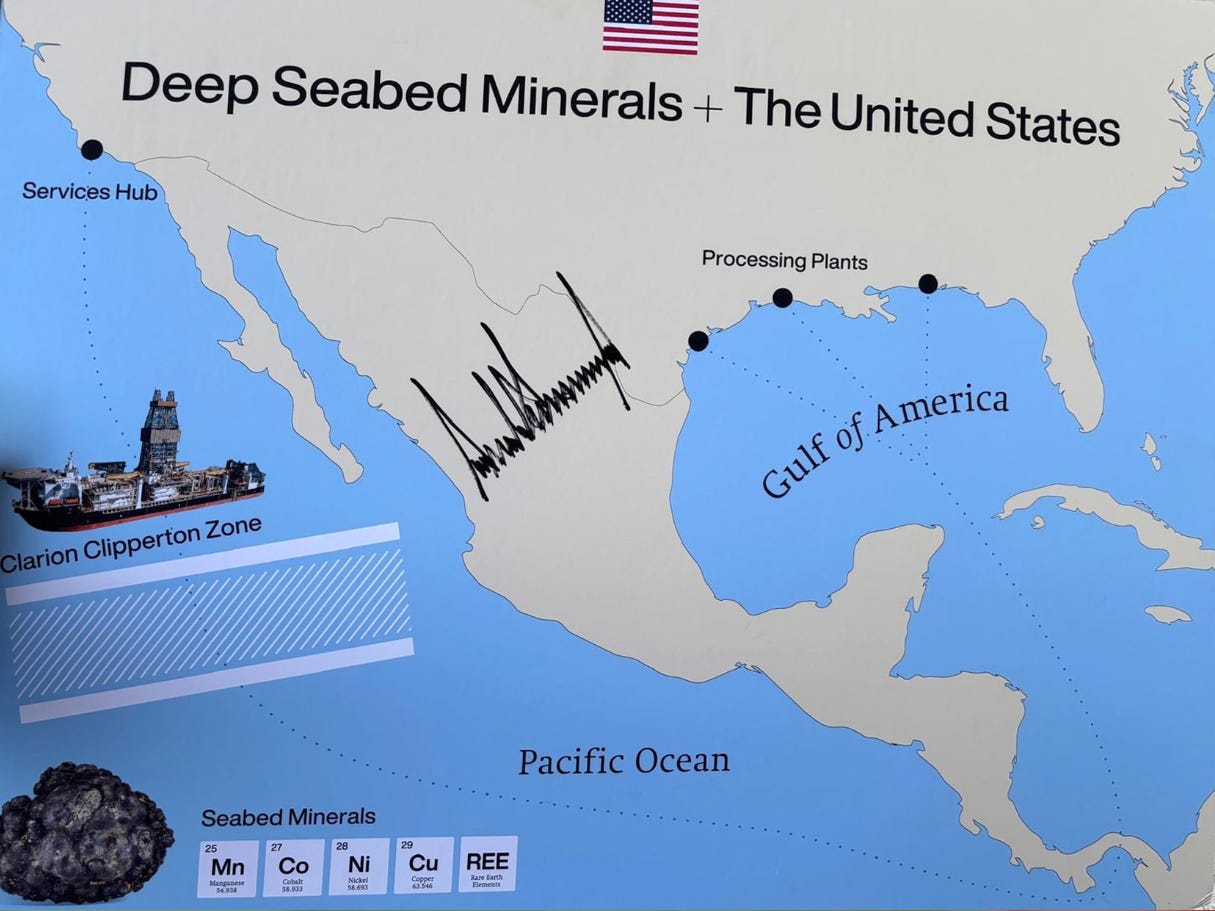

“The United States has a core national security and economic interest in maintaining leadership in deep-sea science and technology and seabed mineral resources,” Trump said in the order.

The order directs the US administration to expedite mining permits under the Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Resource Act of 1980 and to establish a process for issuing permits along the US outer continental shelf.

It also orders the expedited review of seabed mining permits “in areas beyond the national jurisdiction,” a move likely to cause friction with the international community.

The White House says deep-sea mining will generate billions of metric tonnes of materials, while adding $300bn and 100,000 jobs to the US economy over the next decade.

Environmental groups are calling for all deep-sea mining activities to be banned, warning that industrial operations on the ocean floor could cause irreversible biodiversity loss.

“The United States government has no right to unilaterally allow an industry to destroy the common heritage of humankind, and rip up the deep sea for the profit of a few corporations,” Greenpeace’s Arlo Hemphill said.

The 30th session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) Assembly established 1 November as the International Day of the Deep Seabed as proposed by the sponsoring countries, Fiji, Jamaica, Malta and Singapore. The annual observance will promote greater understanding of the deep seabed and its resources while fostering international cooperation in its sustainable management. — Source

Externalities for the Taker Race of people: The price of irreversible ecological damage with deep sea mining could be staggering, estimated to potentially surpass the entire global defence budget of about 2 trillion dollars.

Over 950 marine science and policy experts from more than 70 countries have signed a statement calling for a pause in the development of deep-sea mining.

Trump and Company: Trump’s New Executive Order Promotes Deep Sea Mining in US and International Waters While Bypassing International Law

“You cannot authorize mining that’s going to cause biodiversity loss, that’s going to cause irreparable damage to the marine environment.”

— Matthew Gianni, Deep Sea Conservation Coalition

[Marine biologist Diva Amon explores the deep sea around the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Rocks in the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Brazil.]

So, out of sight, out of mind? The attack on critical thinking, logic, common sense, precautionary principles, and the attack on real science, and research, well well, a Brave New World INDEED.

*****

In an online post last month, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) described the political move as a step towards paving the way for “The Next Gold Rush,” stating: “Critical minerals are used in everything from defense systems and batteries to smartphones and medical devices. Access to these minerals is a key factor in the health and resilience of U.S. supply chains.”

The order, titled “Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources,” charges NOAA and the Secretary of Commerce with expediting the process for reviewing and issuing licenses to explore and permits to mine seabed minerals in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Less than a week after it was issued, a U.S. subsidiary of the Canadian deep-sea mining corporation called The Metals Company submitted its first applications to explore and exploit polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

*****

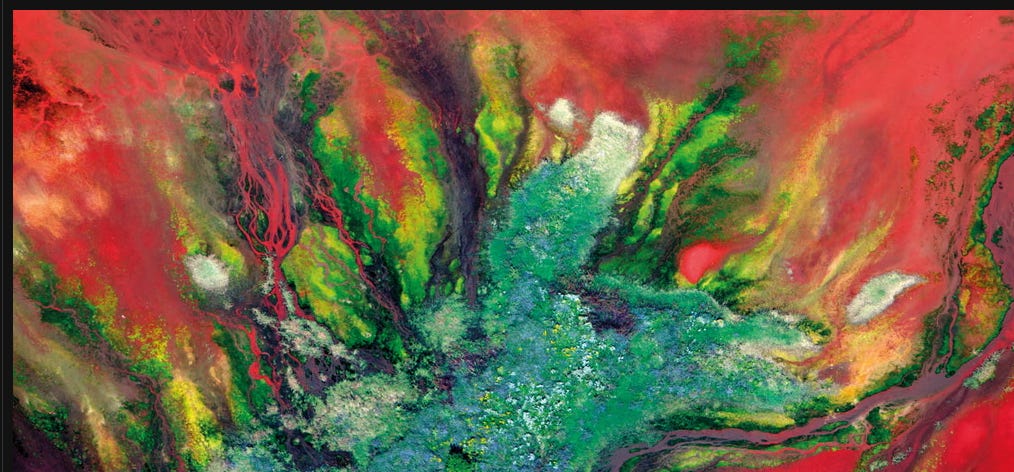

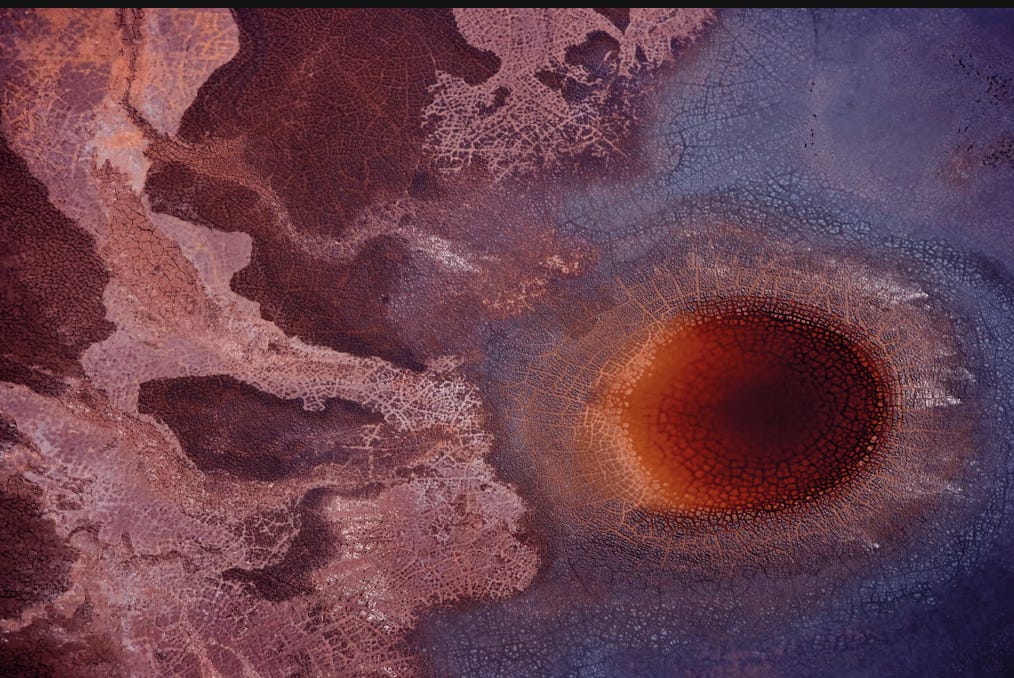

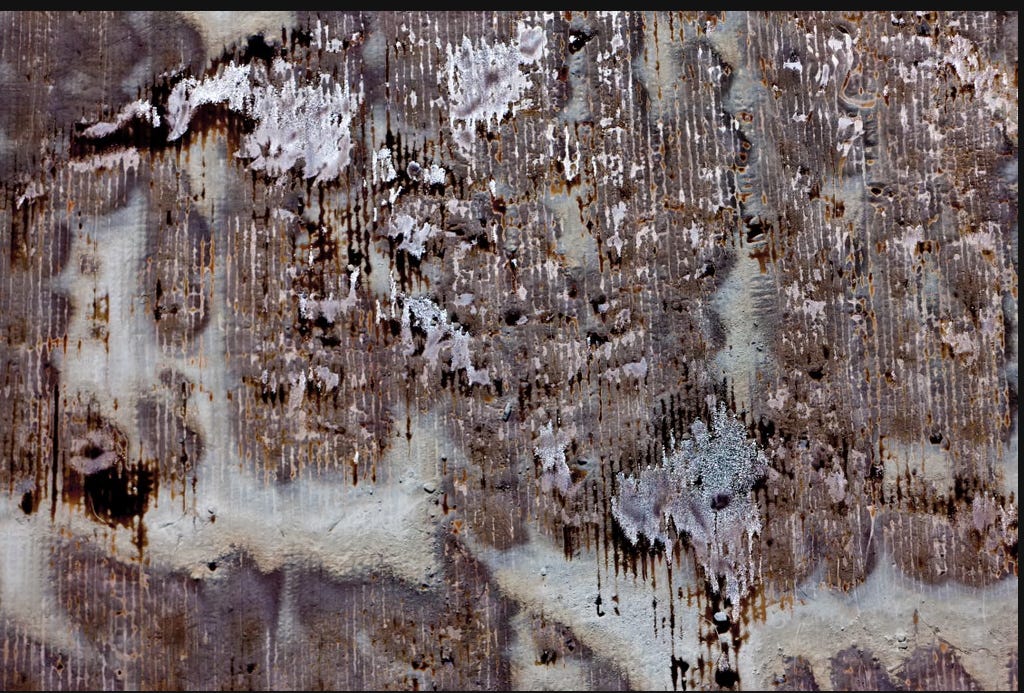

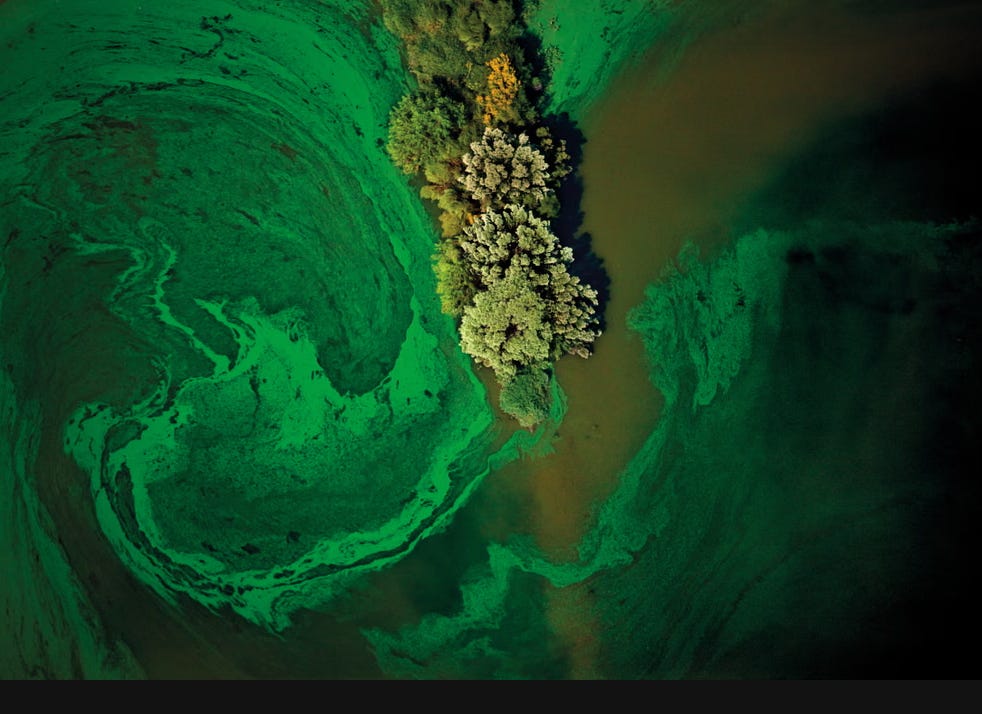

Trigger Warming: Capitalism and Industrialization images cause many to have PTSD.

Acceptable headline? How the Coal Industry Flattened the Mountains of Appalachia –

Acceptable? Green Energy’s Dirty Secret: Its Hunger for African Resources

Considering the “dirty” impacts of critical minerals mining

Oh, business as usual: Amazon rainforest destruction is accelerating, shows government data

Study warns that vast swaths of Amazon are dead –

Worst environmental problems on planet earth?

Match the images above with any of these descriptors”: Potash – Heringen, Germany; Food – Baton Rouge, Louisiana, US, Food – Huelva, Spain (Most of the phosphate rock used to supply fertilizer for southern Europe is mined in Morocco and sent to facilities such as this one in Spain for processing.), Food – Luling, Louisiana US (New evidence contradicts previous claims of the relative safety of glyphosate, the world’s most widely used herbicide, which is manufactured here.), Steel – Kiruna, Sweden, Steel – Burns Harbor, Indiana, US, Copper – Hurley, New Mexico US, Copper – Hurley, New Mexico US, Aluminium – Gramercy, Louisiana, US, Aluminium — Bauxite waste from aluminum production, Oil – Gulf of Mexica, US, Oil – Gulf of Mexico, US, Oil – Fort McMurray, Canada, Fracking – Williston, North Dakota, US, Fracking – Springville, Pennsylvania, US, Coal– Garzweiler, Germany, Coal – New Roads, Louisiana, US, Kayford mountain, West Virginia, US

Find your answerers here: Industrial scars: The environmental cost of consumption – in pictures

The oceans became a dumping ground due to a long-standing “out of sight, out of mind” philosophy, driven by the sheer vastness of the sea, a lack of scientific understanding of pollution’s effects, and the rise of the Industrial Revolution and mass production.

Oh, the Oppen-Monster-Heimers of the world, going to the very deepest parts of the ocean, for . . . ?

Although no complete records exist of the volumes and types of materials disposed in ocean waters in the United States prior to 1972, several reports indicate a vast magnitude of historic ocean dumping:

- In 1968, the National Academy of Sciences estimated annual volumes of ocean dumping by vessel or pipes:

- 100 million tons of petroleum products;

- two to four million tons of acid chemical wastes from pulp mills;

- more than one million tons of heavy metals in industrial wastes; and

- more than 100,000 tons of organic chemical wastes.

- A 1970 Report to the President from the Council on Environmental Quality on ocean dumping described that in 1968 the following were dumped in the ocean in the United States:

- 38 million tons of dredged material (34 percent of which was polluted),

- 4.5 million tons of industrial wastes,

- 4.5 million tons of sewage sludge (significantly contaminated with heavy metals), and

- 0.5 million tons of construction and demolition debris.

- EPA records indicate that more than 55,000 containers of radioactive wastes were dumped at three ocean sites in the Pacific Ocean between 1946 and 1970. Almost 34,000 containers of radioactive wastes were dumped at three ocean sites off the East Coast of the United States from 1951 to 1962.

Following decades of uncontrolled dumping, some areas of the ocean became demonstrably contaminated with high concentrations of harmful pollutants including heavy metals, inorganic nutrients, and chlorinated petrochemicals. The uncontrolled ocean dumping caused severe depletion of oxygen levels in some ocean waters. In the New York Bight (ocean waters off the mouth of the Hudson River), where New York City dumped sewage sludge and other materials, oxygen concentrations in waters near the seafloor declined significantly between 1949 and 1969.

Mustard gas containers, how lovely! Dumped from barges or sent to the bottom aboard scuttled ships, estimates are that millions of pounds of military munitions — unexploded 250-, 500- and 1,000-pound bombs, land mines, mustard gas and other chemical weapons, including munitions confiscated from Nazi Germany and elsewhere following World War II — were sunk the eastern seaboard of the United States, around the Gulf of Mexico and off the coasts of the Hawaiian islands. Records of the dumped munitions, if kept at all, are scarce. Some likely are inaccurate. Some likely were destroyed.

Again, here, the Interview, a month-plus ahead of 91.7 FM airing for DV readers.