“Zionism as a reactionary ideology fitted exactly the ambitions of the British colonialism at that period and later on the American imperialism plans to the areas.”

“The Palestinian resistance movement is not a movement to liberate a geographical 26,000 square km; it is a historical movement which aims to liberate the Jews from zionism and the Arabs from reactionaries, and to establish the Socialist Democratic Palestine. The question of Palestine is the question of a clashing contradiction between the National Liberation movement of the Arabs, headed by the Palestinian national Liberation movement, and imperialism in this part of the world, headed by the zionist movement. And this is how it is a mistake to understand that Israel is just a home of Jews, because Israel is a base of imperialism.”

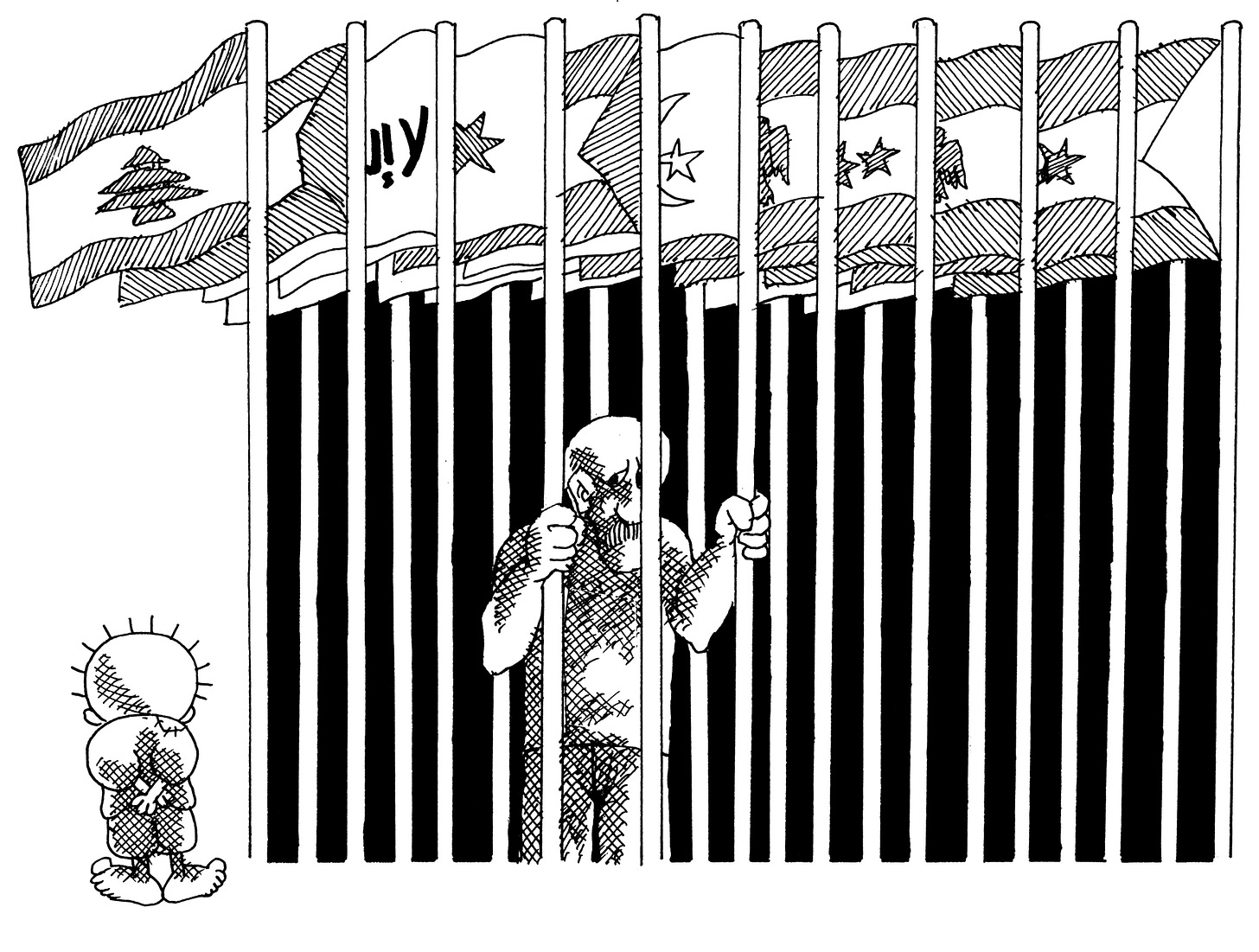

The common narrative of the “Palestinian-Israeli conflict,” while rich in detail and moral urgency, is built upon a fundamental geographical and historical misapprehension. The events of 1948, known to the Arabs as Al-Nakba (the Catastrophe), are almost universally presented as the tragedy of a distinct Palestinian people. This framing, however, obscures a deeper, more profound truth. A critical examination of history, geography, and imperial design reveals that Al-Nakba is not merely a Palestinian wound, but a Syrian one—the violent culmination of a century-long project to prevent the emergence of a unified Arab country in Bilad al-Sham. The struggle of the Arab natives of Palestine against settler-colonial zionism and its imperialist backers is not, in its essence, the “Question of Palestine,” but rather the enduring “Question of Syria.”

I. The Organic Motherland: Syria Before Colonial Dissection

To understand this is to recognize that the political consciousness of the region’s people preceded its colonial dissection by millennia. The modern assertion that there was no Palestinian state is a deliberate anachronism that erases a prior, more organic reality. For millennia, the territory known as Palestine was not a separate political entity but an integral part of Bilad al-Sham, or Greater Syria. This region, encompassing modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and historical Palestine, shared a common culture, economy, and social fabric.

This unity is not a modern nationalist fantasy but a historical fact attested to by the ancient world’s first historian. Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BCE, consistently refers to the entire coastline of the Levant as “Syria.” He makes a clear geographical distinction, noting that the people of the coast “are Syrians who dwell in the parts of Arabia lying along the sea.” This establishes that the inhabitants of this coast were identified as Syrians regardless of sub-regional names, anchoring them within the broader cultural and ethnic fabric of the region. Furthermore, he explicitly names the specific part of this Syrian coast that we call Palestine, not as a separate country, but as a region within it: “Thence they [the Persians] went on to invade Egypt; and when they were in Syria which is called Palestine.”

The cultural unity of the Syrian coast is clearly attested by Herodotus, who records shared practices that bound its peoples together. He observes that the Persians learned to sacrifice to the heavenly goddess from “the Assyrians and the Arabians,”and describes many shared practices, like circumcision, which “the Phenicians and the Syrians who dwell in Palestine confess themselves that they have learnt it from the Egyptians.” Here, he explicitly groups the Phoenicians with the “Syrians of Palestine,” presenting them as a collective entity. This confirms that the entire littoral was understood as a Syrian space, in Arabia, whose peoples shared a common cultural identity.

My own family history is a testament to the endurance of this organic reality into the modern era. My grandfather represented the city of Safad not at a “Palestinian” congress, but in the First Syrian National Congress in 1920. This body, which declared the independence of a united Syria with its capital in Damascus and explicitly included Palestine within its borders, represented the true will of the land. For men like my grandfather, to speak for Safad was to speak for Syria, continuing an unbroken historical consciousness that viewed Palestine and Syria as one and the same—a reality so ancient that it was already a long-established truth when Herodotus recorded it as history two and a half thousand years ago.

Tripoli’s Blood Unites Us.

II. Deconstructing the Fallacy: The Sicily Analogy

A common zionist talking point asserts that there was no sovereign Palestinian state prior to 1948, a statement deliberately used to bolster the lie of “a land without a people.” This argument commits a fundamental logical category error: it conflates the modern political concept of a nation-state with the ancient social reality of a people and their homeland. The absence of a centralized government in a Westphalian model does not mean the land was empty, any more than the absence of a “Sicilian state” meant Sicily was uninhabited. This argument is not just ahistorical; it is a logical absurdity that collapses under the slightest scrutiny. To expose its sophistry, one need only apply the same logic to a different context.

Imagine if the United States, in its 19th-century expansion, had not just conquered the West but specifically targeted the island of Sicily. To secure this strategic foothold in the Mediterranean, it encourages and facilitates the migration of a distinct religious group, say the Mormons, who were once persecuted within the U.S. but now act as a settler vanguard. They establish thriving settlements, citing a two-thousand-year-old religious text that they believe grants them a divine right to the island. The world would rightly view the resistance of the Sicilian people not as an isolated “Sicilian Question,” but as a struggle for Italian territorial integrity—an attack on Italy itself.

Now, imagine these American-backed settlers arguing, “There is no sovereign Sicilian state; therefore, Sicily is a land without a people, ripe for our taking.” This would be immediately recognized as nonsense. Sicily, while not an independent nation-state, is undeniably a foundational part of the Italian nation, with its people being an inseparable part of its social and cultural fabric. To frame the conflict as solely between the “Mormons and the Sicilians” would be to accept the colonial premise and erase both Italy and the role of American power from the map. The absurdity would be compounded if the conflict was then mislabeled a “clash between Mormons and Catholics,” thereby masking the core issues of land, sovereignty, and a state-sponsored colonial conquest.

This refined analogy precisely mirrors the deception at the heart of the colonial narrative on Palestine. It captures the dynamic of a great power using a settler project to achieve its strategic aims. To claim there was no Palestinian state is as irrelevant as claiming there was no Sicilian state. Palestine was not an island in the Mediterranean—it was an integral part of Syria. Its people were Syrians. The attempt to retroactively justify conquest by applying a modern political standard to an ancient land is not a historical argument; it is the propaganda of dispossession.

III. The Imperial Genesis: From Napoleon to Sykes-Picot

The “Syria Question” for the British Empire truly began not with the Balfour Declaration, but with Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt and Palestine in 1798. This was a direct strategic thrust aimed at severing Britain’s route to its most prized possession: India. Although Napoleon was defeated, the shockwave he sent through the British Admiralty never faded. From that moment, controlling the land bridge of Bilad al-Sham—particularly the corridor of Palestine—became a paramount imperial imperative for London. Any potential threat to that route, whether from a resurgent France, a weakening Ottoman Empire, or later, a unified Arab state, had to be preemptively neutralized.

This long-standing strategic anxiety culminated in the ultimate act of colonial cartography: the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. This secret pact between Britain and France did not simply redraw borders; it surgically dismembered the body of Bilad al-Sham, deliberately fracturing a unified cultural and economic sphere into the artificial, competing mandates of Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine. The creation of “Palestine” as a separate British Mandate was not an accident of history; it was a deliberate strategy to isolate and control the most geostrategically sensitive portion of the Syrian homeland.

IV. The First Arab Threat and the Zionist “Solution”

The first major test of this new colonial order came from Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt and his son Ibrahim Pasha, who in the 1830s swept through Bilad al-Sham, threatening to create a powerful, modernizing Arab state that could challenge both the Ottomans and European influence. British policy reacted with alarm. As the historian George Antonius noted, Britain’s resistance to this nascent Arab state was fundamental. This is chillingly confirmed by British Foreign Minister Lord Palmerston, who wrote in 1833:

“The real goal of Muhammad Ali is to establish an Arab kingdom that includes all the countries that speak Arabic… Moreover, we see no reason that justifies replacing Turkey with an Arab king in control of the route to India.”

It was in this context—the need to secure the route to India by ensuring a fragmented and controlled Syria—that British colonial strategists began to see a “zionist” solution decades before the Austrian Theodor Herzl. In September 1840, the Earl of Shaftesbury, a key influencer of British policy, explicitly proposed the establishment of a British colony in Syria and argued for the settlement of Jews in Palestine. He wrote that the region needed capital and labor, and that the “Hebrews were anticipating a return to Syria.” He concluded that employing the Jews was the “cheapest and most guaranteed method” to develop and control this sparsely populated, strategic land bridge.

A quarter-century later, in 1856, Shaftesbury was even more explicit, asking: Does Britain not have an interest in this? He answered:

“It would be a blow to England if any of its rivals were to seize Syria. Its empire… would be cut in two. England must preserve Syria for itself… [and] should foster the nationalism of the Jews.”

As Nahum Sokolow, one of the founders of zionism, later noted, the British strategic mind had already, by the mid-19th century, linked the “future of Palestine” directly to the security of the Empire. British colonialism had become functionally zionist before the European political zionist movement itself was formally born.

V. The Strategy of Perpetual Fragmentation: From Pipelines to Proxy Wars

The colonial dismemberment of Bilad al-Sham did not conclude with the Sykes-Picot Agreement or even the Nakba of 1948; it evolved into a perpetual strategy to ensure the region’s permanent weakness and subservience. This policy of intentional fragmentation, which relies on and inflames sectarian, ethnic, and regional divisions, has been a consistent weapon in the imperial arsenal to preempt the re-emergence of a unified, independent Arab power. The motivation for this is twofold: a long-standing geopolitical imperative and a more recent, critical struggle over energy dominance.

The visionary Palestinian writer and revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani, in his study The Arab Cause During the Era of the United Arab Republic, identified the internal dimension of this strategy with chilling precision. He argued that colonialism and its zionist spearhead found natural allies in the region’s internal divisions:

“There is no doubt that the reactionary, the opportunist, the regionalist, and the sectarian… meet in their goals with the goals of Israel and colonialism, whether they intended that or not… In fact, the reliance of colonialism and Israel on this trio is almost complete.”

As definitive proof, Kanafani cited a declassified Israeli plan from 1957, which laid out a blueprint for the systematic destruction of Arab unity. The plan called for rapid measures to establish a Druze state, a Shiite state in Lebanon, a Maronite state, an Alawite state in Syria, a Kurdish state in Iraq, and a region for the Copts. This document was not merely speculative; it was a reflection of a core strategic understanding that the survival of the colonial implant depended on ensuring the motherland remained divided. As Kanafani noted, this plan “resulted from a feeling that there are tendencies in the indicated regions for secession,” and its purpose was to exploit those tendencies to “establish any defeatist ability in the Arab homeland.”

This century-old strategy of balkanization was violently re-energized in the 21st century, driven by a new and critical geopolitical prize: control over energy corridors. As analyses have revealed, the struggle in Syria is the latest episode in a “pipeline war” whose roots stretch back to the mid-20th century. This conflict reached a critical juncture in 2009, when Qatar proposed a massive pipeline project that would run from its North Field, through Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Syria, to Turkey, with the aim of supplying European markets. This Qatari pipeline, backed by the United States, was in direct competition with a rival Iranian proposal that would run from Iran through Iraq and Syria. Syria’s refusal in 2011 to agree to the Qatari pipeline, in part to protect the strategic interests of its ally Russia, the dominant gas supplier to Europe, was the decisive geopolitical event that ignited the modern phase of this conflict.

This economic rejection coincided with the U.S. policy, revealed by WikiLeaks, of aggressively pursuing “regime change” in Syria. The subsequent war, fueled by foreign powers, cannot be disconnected from this struggle over which global powers would control the energy future of Europe and isolate Iran. The pipeline competition provided a powerful economic and strategic motive for certain external actors to actively pursue the fragmentation of Syria, using the very sectarian and regionalist playbook outlined in the 1957 Israeli document. The goal was to either install a compliant government in Damascus or, failing that, to balkanize the country into weaker, controllable statelets, thereby securing the transit route and dealing a blow to their rivals.

Thus, the ongoing tragedy in Syria is not a separate “conflict,” nor did it spring from internal strife. It is the continuation of the same war declared on Bilad al-Sham over a century and a half ago. The support for separatist militias, the manipulation of opposition groups by imperialist and foreign intelligence agencies, the fueling of sectarian strife, and the economic siege are all modern tools to achieve an ancient European colonial goal, now supercharged by the geopolitics of energy: to ensure that the Syrian wound never heals, that the motherland never reunifies, and that the Question of Syria remains unanswered, leaving its land and resources open to external domination.

The Unanswered Question of Syria

To understand Al-Nakba as a Syrian wound is to restore the struggle to its proper scale and historical genesis. It moves the discussion beyond the cramped confines of the failed paradigm of the “two-state solution,” revealing the struggle as what it has always been: the central battle in the long war against the imperial division of the Eastern Mediterranean—a division initiated to secure the route to India; cemented by Sykes-Picot; and consummated by the shameful Balfour Declaration. The “Question of Syria” is the question of a land struggling for reunification and liberation from this imperial legacy. The struggle in Palestine is not a local border dispute; it is the fight for the integrity of the motherland. Until this foundational reality is acknowledged, any analysis of the struggle will remain incomplete, treating the symptoms while ignoring the amputation that afflicts the entire body of Bilad al-Sham.

- This essay relies significantly on historical documents, quotes and analysis compiled by Emile Touma in his seminal Arabic-language work, The Roots of the Palestinian Cause.