AP (4/13/25) attributes Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa’s re-election to “voters weary of crime”—even though murders rose sharply under his administration.

Elections in Latin America are often controversial. While many countries in the Global North regularly shuffle between parties offering alternating versions of neoliberalism, voting in Central and South America often offers starker contrasts: An anti-imperialist candidate in the mold of Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez might be up against a neoliberal such as Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro. It could hardly be otherwise, in a region with the world’s biggest gap between the richest and poorest.

North American and European corporate media are conscious of this complexity, but rarely convey it to their readers, instead issuing reports that lack sufficient context or history. Washington’s influence on their messaging—as if the media had their own Monroe Doctrine—is never far below the surface, especially when it comes to reporting political turning points such as elections. Doubts about the results, or questions about outside influence, can be set aside if the outcome fits the consensus narrative, especially if it is endorsed by a White House spokesperson, or a surrogate body like the Organization of American States (OAS).

Ecuador provides an example. Its President Daniel Noboa, son of the country’s richest landowner, began his second term of office on May 25. He was declared victor by a huge margin in a run-off election on April 13, even though his opponent, leftist Luisa González, virtually tied with him in the first round in February.

According to the corporate media, Noboa’s victory was clear-cut, the reasons for it were obvious and there was little reason to question the outcome. The Washington Post (4/13/25) headlined “President Who Declared War on Ecuador’s Drug Gangs Is Reelected.” The Wall Street Journal (4/13/25) said “Ecuador Re-Elects Leader Fighting War on Gangs Smuggling Cocaine to US.” The New York Times (4/13/25) proclaimed that “Ecuador’s President Wins Re-Election in Nation Rocked by Drug Violence.” The headlines were so similar they might have been modeled on the agency story from the Associated Press (4/13/25): “Daniel Noboa Is Reelected Ecuador’s President by Voters Weary of Crime.”

Linking the election to the war on drugs added a useful North American perspective. And, of course, this could be strengthened by reminding readers that Noboa is an ally of Donald Trump, as the Post, Journal and Times duly did.

‘Increasingly authoritarian’

The New York Times (4/13/25) dismissed candidate Luisa González as someone “largely seen as the representative of the former president” Rafael Correa, who is condemned for his “authoritarian tendencies.”

Had González won instead, she would have become Ecuador’s first female president (aside from Rosalía Arteaga, who was president for two days in 1997). However, all three outlets felt it necessary to remind readers of her dangerous link to former President Rafael Correa, known for “antagonizing the United States,” as the Post put it. The Times patronizingly suggested she would be Correa’s “handpicked successor,” or even “the representative of the former president, a divisive figure in Ecuador” (emphasis added), who (the Post claimed) “grew increasingly authoritarian” before he left office in 2017.

This grossly inverts history. Arguably, Ecuador “grew increasingly authoritarian” after Correa’s presidency (FAIR.org, 8/17/20). His party, and three others, were banned in 2020. This decision was later reversed, but then both Correa and his vice president, Jorge Glas, were convicted of corruption, in what appeared to be obvious cases of “lawfare,” based on evidence from a source funded by the US National Endowment for Democracy.

Correa fled to Belgium, where he was granted asylum. Glas spent five years in prison and, seriously ill and facing new charges after Noboa first took office in late 2023, was granted asylum by Mexico. He never managed to leave Quito, because Noboa had him violently abducted from Mexico’s embassy and thrown into prison, in a clear breach of international law (London Review of Books, 4/9/24).

Five years of escalating violence

Correa had successfully reduced violence in Ecuador, making it one of Latin America’s safest countries. Progress was reversed under successive neoliberal governments, beginning with President Lenín Moreno. Victims have included several political figures, but the most egregious incident occurred only five months ago under Noboa’s presidency, when a group of soldiers captured, tortured and then murdered four children in Ecuador’s second city, Guayaquil (El Pais, 5/5/25).

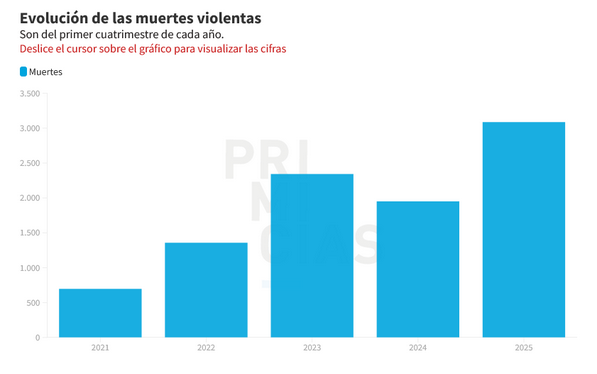

Source: Primicias (5/21/25), based on Ecuadorian police data for the first four months of each year.

Violence continues to escalate, despite Noboa’s promises to tackle it. The first four months of 2025 saw a 58% increase in homicides, compared with the same period in 2024 (see chart), turning Ecuador into the most dangerous country in the Americas. Much violence is related to drug trafficking, with Ecuador now “an open funnel for cocaine exports and money laundering” under recent right-wing governments (London Review of Books, 4/30/25). Despite being part of the problem, Noboa maintained that only he could solve it, offering to adopt the hardline policies for which El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele has become famous.

Ecuador’s contested ballot

After the media chorus of welcome for Noboa, it seems almost churlish to ask if he really won a clean election. Yet while Foreign Policy (4/17/25) said his win was “not surprising,” it certainly did surprise many commentators. It is instructive to review the evidence, starting with the first round of the elections and ending with the results of the final round.

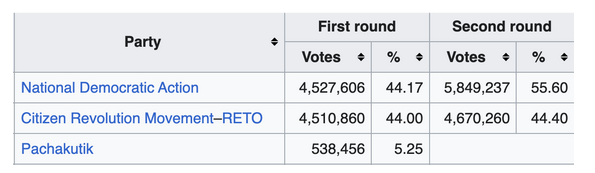

February’s first round could hardly have been closer, with Noboa gaining 44.17% of the votes, barely ahead of González with 44.00% (see table), a difference of only 16,746 votes. Turnout was 82%. The result suggested that opinion polls were exaggerating Noboa’s popularity, since for the preceding month they had given him a comfortable average lead.

A third candidate, representing the largest Indigenous party, garnered 5.25%, and was obliged to drop out ahead of the final top-two round two months later. This candidate would later support González, but smaller Indigenous parties would favor Noboa.

Source: Wikipedia.

The electoral campaign period saw a series of illegal moves on Noboa’s part. He refused to step down temporarily, as required constitutionally. Instead he suspended his vice-president, Verónica Abad, ignoring a court ruling that she should temporarily replace him and shut her office (Financial Times, 1/18/25). A right-wing rival was barred from standing, and Ecuadorians in Venezuela were denied the vote while their compatriots elsewhere were not.

Noboa’s massive social media campaign was allegedly financed from public funds (La Calle, 10/22/24); troll centers were established to attack his opponent (Pandemia Digital, 2/3/25). Bonuses costing over $500 million were paid to hundreds of thousands of poor Ecuadorians from public funds (Primicias, 3/28/25); CEPR’s Mark Weisbrot dubbed this “vote buying,” at an estimated $475 each. Noboa was photographed with Trump, Ecuador’s Washington embassy having paid at least $165,000 for the opportunity (People’s Dispatch, 4/6/25).

Like El Salvador’s Bukele, Noboa enhances his powers by declaring states of emergency. Prior to the poll on April 13, he declared one that covered the capital and several urban centers which González had won in the first round, intimidating voters and allowing unannounced searches (CBS News, 4/12/25). On election day, machine gun–bearing soldiers were posted at polling stations. Even so, two exit polls showed a close result, one indicating a win by González. During the count, images were posted of voting sheets published by the Noboa-manipulated electoral council that were invalid because they were unsigned.

‘Impossible’ result

The April 13 results were extraordinary, awarding Noboa victory by a full 11.25 percentage points. They gave Noboa 1.3 million more votes than he won in the first round, while González gained only 160,000. This happened despite the first-round tie, González’s endorsement by the leading Indigenous candidate, opinion polls slightly favoring her, two close exit polls and a much smaller difference (2 percentage points) between the two candidates’ parties in the simultaneous vote for the National Assembly.

Former President Rafael Correa wrote in his X account:

Ecuadorian people: You know that, unlike our adversaries, we have always accepted the opponent’s victory when it has been clean. This time it is NOT. Statistically, the result is IMPOSSIBLE.

González’s requests for recounts were twice rejected by the judicial bodies governing the election, in a series of decisions demonstrating bias in Noboa’s favor. Several leftist presidents, such as Colombia’s Gustavo Petro and Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum, endorsed González’s protests, and the latter refused to recognize Noboa’s presidency.

Truthout (5/2/25): “President Noboa carried out one of the dirtiest and unequal campaigns in memory—relying on fake news, vote buying and threats.”

A week after the poll, Denver University Professor Francisco Rodríguez published a statistical comparison of the result in Ecuador with 31 other recent Latin American run-off elections. He concluded that Ecuador’s was “not normal,” and “deviates sharply from regional experience.” He said he was not claiming fraud, but was calling for careful scrutiny.

Ecuadorian political sociologist Franklin Ramírez Gallegos went further in Truthout (5/2/25): “These were absolutely unequal, opaque, fraudulent elections,” he said. Within a few days of the election, there were reports of Noboa’s opponents being persecuted, and of a “blacklist” naming more than 100 people to be tracked down.

None of the US corporate media suggested the election was problem-free. But where, for example, they reported that González had claimed fraud, they qualified this by saying she did so “without presenting evidence” (Washington Post, 4/13/25). They also repeated Noboa’s phony counterclaims of irregularities (AP, 4/13/25). Reassurances by electoral observers from the OAS and US State Department were duly cited (Reuters, 4/14/25).

Framing Latin American elections

The New York Times (10/23/19) shows highly selective skepticism over Latin American electoral results.

The OAS has a 70-year history of bending to Washington’s whim when judging elections. Media reliance on its verdicts, despite—or really because of—its close alignment with US interests, speaks to the wider problem of media reporting of Latin American elections. Here are just three further examples—of many.

In 2019, the unsubstantiated findings by OAS observers of faults in the presidential election in Bolivia were swallowed wholesale by corporate media (FAIR.org, 11/18/19). The New York Times, citing the OAS’s “withering assessment” (10/23/19), quickly scorned the “highly fishy vote” (11/11/19) which extended the presidency of leftist Evo Morales. It turned out not to be fishy at all, but before the truth emerged, Morales had resigned, faced likely assassination and fled to Mexico. Morales’s forced resignation by Bolivia’s rightist-aligned military was called a “coup” by Argentina and Mexico.

The year before, when Bolsonaro won the election in Brazil while his principal opponent, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, was imprisoned (later to be released, post-election), the Times published 37 relevant articles, but not one examined the falsity of the charges. Reporting from Brazil, journalist Brian Mier (FAIR.org, 3/8/21) observed that this “helped normalize” Bolsonaro’s victory and “opened the door for a neofascist/military takeover of Brazil.”

In Honduras in 2013, after the neoliberal candidate Juan Orlando Hernández had “all the ducks lined up for a fraudulent election” (London Review of Books, 11/21/13), the Washington Post (11/26/13) produced a scurrilous editorial claiming that his victory had avoided a dictatorship. Instead, it created one: Hernández won two fraudulent elections, was extradited on drug charges after leaving office, and is now in a US prison.

After the dubious victory

Since the election, Noboa has been busy in pursuing the “blacklisted” political opponents who tried to stand in his way. A few days before his May 25 investiture, dubious charges were pressed against former presidential candidate Andrés Arauz. It was Arauz who published the images of invalid voting sheets on April 13—to no avail, as they were ignored not only by the electoral authorities, but by the observers from the OAS and European Union.

Noboa’s big if highly questionable victory will strengthen his hand in creating a permanent and violent security state. Blackwater’s founder Erik Prince was hired in April to help him in the task. Two new military bases, one of them in the Galápagos Islands, have been offered to the US, in defiance of a prohibition on foreign bases in Ecuador’s constitution—a prohibition that the National Assembly rescinded this month at Noboa’s request.

On April 30, the Defense and interior ministers were pictured in El Salvador, inspecting Bukele’s notorious CECOT prison (Infobae, 4/30/25). Presumably these are the first steps in delivering the promise, made in Noboa’s short and vacuous speech at the investiture last month, to “rescue” Ecuador.

- Originally published at FAIR.org.