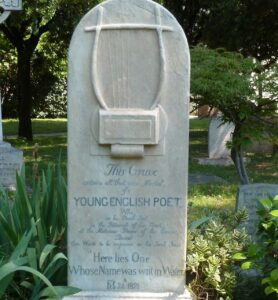

On the Romantic poet John Keats’ tombstone in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome are these words, which he chose: “HERE LIES ONE WHOSE NAME WAS WRIT IN WATER.”

His name is not there, by choice. Keats was twenty-five when he died. In Ode to Psyche he wrote:

His name is not there, by choice. Keats was twenty-five when he died. In Ode to Psyche he wrote:

Yes, I will be thy priest, and build a fane

In some untrodden region of my mind,

Where branched thoughts, new grown with pleasant pain,

Instead of pines shall murmur in the wind:

…………………………………………………………………………………………..

And in the midst of this wide quietness

A rosy sanctuary will I dress

With the wreath’d trellis of a working brain,

With buds, and bells, and stars without a name,

With all the gardener Fancy e’er could feign,

Who breeding flowers, will never breed the same.

On the American writer James Agee’s burial stone in an isolated wooded spot off a dirt road in upstate New York, there are no words, although I like to think Keats’ poetic words seem appropriate to the sylvan nature of the spot and the bird song that filled the air in praise when I and my wife “trespassed” onto land that once meant so much to Agee, and where the house he once sought refuge in lies dilapidated and mute.

I read somewhere that he wished that a bird would be carved into the stone under which he was placed, but it is absent. Perhaps a phoenix, that symbol of the triumph of life over death and immortality, so dear to D.H. Lawrence. Maybe it, like him, flew away, and maybe a young man like Keats, who died so long before him, could conjure winged words of praise – doves of the spirit – for a man who would come long after him, nearly a century and a half after, because he sensed a connection that he could send flying into the future. Like Emily Dickinson, he knew hope was a thing with feathers, and the bird of time has no limits when it is released from the sentence. Time? Not a magazine where Agee once worked – but the real mystery and obsession of true artists. Time, death, and the fact that love brought us into existence. “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all /Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know,” wrote Keats.

Keats and Agee were pilgrims, and Agee no doubt would agree with Keats’ words that “this life is a vale of soul-making.”

Many people visit Keats’ and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s graves in the Roman cemetery; few ever have or will pay homage to Agee over the boulder that marks the spot where his body was placed after he died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-five in a NYC taxi on May 16, 1955, seventy years ago. He has largely been forgotten. If you are reading this, you may have no idea who he was and why I am writing this. I will tell you.

I am writing this because I have felt a connection to him since I was a young man, not just to his talent, but his passionate soul, beautiful writing, the religious quality of his strivings, his faith and doubt, and his sense of wonder and reverence before the mystery of existence. His deep moral outrage at the suffering forced on the poor by the rich is close to my heart, and the desperate way he threw himself into life, always aware since the age of six when his father died in an automobile accident that death shadows our every move on our short visits through life. All his work is filled with the sense of the mysterious nature of existence as described by Einstein:

The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed.

Agee’s eyes were always wide-open; he saw through them the hope and hopelessness that battle in every heart.

I am a minor writer whose work is essentially ignored, which I understand but wish wasn’t so. But I know also that recognition is not why I write; I do it because it is my effort at soul-making, which is as much a restorative endeavor as a prospective one. Agee wrote for his soul. Years ago he grasped my ironically young-old mind when he wrote:

Now as awareness of how much life is lost, and how little is left, becomes ever more piercing, I feel also, ever more urgently, the desire to restore, and to make a little less permanent, such of my lost life as I can, beginning with the beginning and coming far forward as need be. This is the simplest, most primitive of the desires which can move a writer. I hope I shall come to other things in time; in time to write them. Before I do, if I am ever to do so, I must sufficiently satisfy this first, most childlike need.

We are all little lost children at heart, disguised to ourselves as adults, doing what we do to find the natural piety that Wordsworth said was “the Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star.” When the living ignore my work, I often shamefully respond like a hurt child, but it is just a small step to the realization that Agee and Keats shared, that we will all be forgotten in due time, that we are bubbles on the great stream, and recognition is a fool’s dream. Fugitives from our true vocations, we often engage in endless imitation, something Agee never did. To say he was true to his life’s star is to say he was never a copy but always an original.

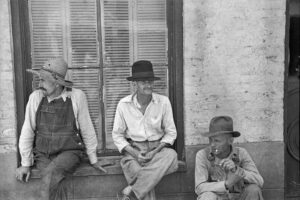

He was the author of the posthumously acclaimed (but failure in his lifetime) classic account of dirt-poor Alabama tenant farmer families during the Depression, with searing photographs by Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (the Foreword begins on page 75), the posthumously published Pulitzer Prize winning beautiful autobiographical novel, A Death in the Family, film scripts for The African Queen (1951) and The Night of the Hunter (1955), and unique film reviews for Time and The Nation magazines, among other works. Agee, a poet at heart, was acutely aware that he, and all of us over time, will be forgotten, but while the thought is upon me – before I too am extinguished like a brief spark on a chimney wall – of how powerful a writer he was and how full of moral passion his yearnings and how beautiful his prose, let me offer this long quote from an undated fragment he wrote for use in his rapturously sad A Death in the Family, a novel based on the six year-old Agee’s reaction to his father’s death in an automobile accident near their home in Knoxville, Tennessee in 1915:

Those who have gone before, backward beyond remembrance and beyond the beginning of imagination, backward among the emergent beasts, and the blind, prescient ravenings of the youngest sea, those children of the sun, I mean, who brought forth those, who wove, spread the human net, and who brought forth me; they are fallen backward into their graves like blown wheat and are folded under the earth like babies in blankets, and they are all melted upon the mute enduring world like leaves, like wet snow; they are faint in the urgencies of my small being as stars at noon; they people the silence of my soul like bats in a cave; they lived, in their time, as I live now, each a universe within which, for a while, to die was inconceivable, and their living was as bright and brief as sparks on a chimney wall, and now they lie dead, as I soon shall lie; my ancestors, my veterans. I call upon you, I invoke your help, you cannot answer, you cannot help; I desire to do you honor, you are beyond the last humiliation. You are my fathers and my mothers but there is no way in which you can help me, nor may I serve you. You are the old people and now you rest. Rest well; I will be with you soon; meanwhile may I bear you ever in the piety of my heart.

Piety has become a lost virtue (from Latin pietatem (nominative pietas) dutiful conduct, sense of duty; religiousness, piety; loyalty, patriotism; faithfulness to natural ties), as have so many others such as honor, courage, truthfulness, etc. Agee was no exemplar of every virtue, but in that he was like all of us, frail and flawed, but his audacious courage in his writing was his way to redeem his child’s soul by never holding back like so many writers do. He always drew on what was deep and true in his experience, especially the lacerating wound he suffered when his father died. That preoccupation, that youthful revelation, that presence of an absence, that hole in his heart, that death at an early age, joined to his youthful Christian devoutness and doubt, can be seen in everything he wrote.

That he came to think his ancestors could not help him was mistaken, I would say; for the bridge over the river between life and death, across the rivers Acheron and Styx, which separate the worlds of the living and the dead in Greek Mythology, runs two ways when one trusts the heart not the head. Agee, like Aeneas whom Virgil so often describes as pius in the Aeneid, was essentially a man of the heart, a rough Tennessean schooled at Harvard and in the sophisticated secular precincts of New York City where he may have turned a bit away from his youthful faithful heart under the strain of the heart attacks that killed him and the ideology of that “sophisticated” culture.

Like Agee’s father, my wife’s father died in a single car crash on a bridge at night when she was two months old. I have seen how that presence of his absence – the father that she never knew and her family’s reaction to his death: silence – affected her. Her courage in facing it inspires me. Agee, at least, had the father he loved dearly for six years, so the absence of his presence was different but similar. Who can say which was worse, the loss of presence or a lifelong absence?

When I was five years old, my mother, nine months pregnant, went to the hospital to give birth to another sibling (there were five of us already), and we were all very excited. Something happened; the baby was stillborn. When my father took me to the hospital to see my mother, I was not allowed in, but the figure of her sad face waving to me from the window on the second floor has stayed with me across the years. When I was ten years-old, my six year-old cousin accidentally shot and killed his eight year-old brother with a rifle that was hidden under a bed in a neighbor’s home. There is more, and no doubt many people have such stories to tell, but I offer these examples to reveal some of the impulses for my writing this essay about James Agee, just as one can explore the reasons behind Agee’s writing and behavior, or that of all the actions of those who never wrote a word but were marked by death in their tender years. For some, tragedy elicits words; for others, the mystery renders them mute.

Being a master of the English language and a writer from an early age with music in his words, Agee tells us at the end of his book, The Morning Watch, that when he (Richard in the book) was twelve years-old at a religious boarding school on Good Friday, feeling a new, heavy, “cold, crushing sorrow” at the thought of Jesus’s suffering, he saw hogs devour a wounded snake and felt such horror and pity, that he said to himself that:

. . . he was so far gone by now that there must be a way beyond really feeling anything, ever any more (the phrase jumped at him): (Who had said that? His mother. ‘Daddy was terribly hurt so God has taken him up to heaven to be with Him and he won’t come back to us every any more.’) ‘Ever any more,’ he heard his quiet voice repeat within him; and within the next moment he ceased to think of the snake with much pain.

Agee was such a deep feeling writer that it was impossible for him to get beyond really feeling anything, ever any more. Some critics have accused him of being too emotional and also of never having fulfilled his promise. In a luminous memoir, his good friend, Robert Fitzgerald, the poet and translator of the Odyssey and the Aeneid, puts that canard to rest:

Quite contrary to what has been said about him, he amply fulfilled his promise. In one of his first sonnets he said, of his kin, his people

‘Tis mine to touch with deathless their clay,

And I shall fail, and join those I betray.In respect to that commission, who thinks there was any failure or betrayal?

As for those poor tenant farmer families that he praised in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men – the book that started with a commission from Fortune magazine where he was working in the 1930s to write an article that Fortune never published – Agee began it thus:

I spoke of this piece of work we were doing as ‘curious.’ It seems to me curious, not to say obscene and thoroughly terrifying that it could occur to an association of human beings drawn together through need and chance and for profit into a company, an organ of journalism, to pry intimately into the lives of an undefended and appallingly damaged group of human beings, an ignorant and helpless rural family, for the purpose of parading the nakedness, disadvantage and humiliation of these lives before another group of human beings, in the name of science, of ‘honest journalism’ (whatever that paradox may mean), of humanity, of social fearlessness, for money, and for a reputation for crusading and for unbias which, when skillfully enough qualified, is exchangeable at any bank for money (and in politics for votes, job patronage, abelincolnism, etc.’); and that these people could be capable of meditating this prospect without the slightest doubt of their qualifications to do an ‘honest’ piece of work and with a conscience better than clear, and in the virtual certitude of almost unanimous public approval. . . . And it seems curious still further that, with all their suspicion , save only for the tenants and themselves, and their own intentions, and with all their realization of the seriousness and mystery of the subject, and of the human responsibility they undertook, they so little questioned or doubted their own qualifications for this work.

All of this, I repeat, seems to me curious, obscene, terrifying, and unfathomably mysterious.

Those are the words of a man who didn’t mince words.

So let us now join with him in praising these famous men and all like them who struggle to eke out a living against the predations of the wealthy hyenas with smiling faces whose fortunes are built on the backs of working people.

And let me now praise James Rufus Agee who died on this day, May16, 1955. He spoke for the human family, that one death was everyone’s, and as Wordsworth put it, we should give thanks for his life and give

Thanks to the human heart by which we live,

Thanks to its tenderness, its joys, and fears,

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.

May James Agee speak to us still, if only we would listen.