…all those McCarthy-Loving Feds and Politicians have tapped the nerds and software billionaires to watch our every fucking move!!!!!!!

Badges? We ain’t got no badges. We don’t need no badges. I don’t have to show you any stinking badges!

The real quote from B. Traven’s book, Treasure of Sierra Madre.

“Badges, to god-damned hell with badges! We have no badges. In fact, we don’t need badges. I don’t have to show you any stinking badges, you god-damned cabron and ching’ tu madre! Come out there from that shit-hole of yours. I have to speak to you.”

(For the Spanish-deprived among you, “cabron” is cuckold, “chingar” is “fuck,” and “tu madre” is “your mother.” Clearly the dialogue was cleaned up for the film.)

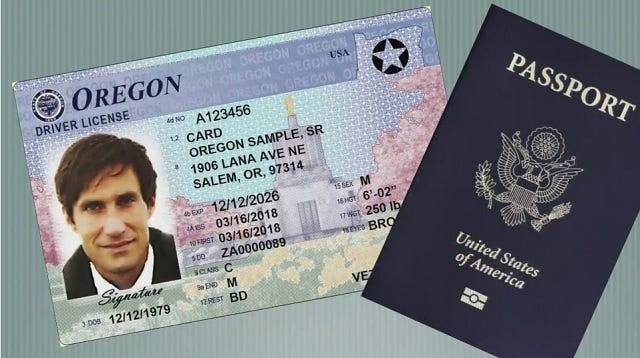

Oregon offers both a standard card and a Real ID Act-compliant card. Both types of cards allow you to legally drive and prove identity and age for things such as cashing a check. *Beginning May 7, 2025, a standard card cannot be used to board a domestic flight. See the TSA website for federally acceptable documents. [Does the passport work for domestic travel starting May 7, 2025?]

Federal banking laws and regulations do not prohibit banks from requesting that you provide a fingerprint or thumbprint to cash a check. Banks may use fingerprinting as a security measure and a way to combat fraud.

Employers sometimes check credit to get insight into a potential hire, including signs of financial distress that might indicate risk of theft or fraud. They don’t get your credit score, but instead see a modified version of your credit report.

Employer credit checks are more likely for jobs that involve a security clearance or access to money, sensitive consumer data or confidential company information. Such checks may also be done by your current employer before a promotion.

Pre-employment drug tests are required by some employers as a condition of job offers.

• These tests typically screen for the presence amphetamines, marijuana, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine, but employers can also request testing for additional substances.

• Pre-employment drug tests help protect workplace safety and boost productivity while reducing accidents and turnover.

• Testing methods can include urine, saliva, hair, and blood, but urine is the most common.

• Most employers in regulated industries are required to perform pre-employment drug tests. Private-sector, non-regulated employers are not required to conduct pre-employment drug tests but can do so as long as they comply with state and local laws.

Criminal Records Check and Fitness Determination/ OAR 125-007-0200 to 125-007-0330/ Status: Permanent rules effective 1/14/2016

Overview:

The Oregon Department of Administrative Services (DAS) implemented statewide administrative rules related to certain aspects of criminal records checks on January 4, 2016 (ORS 181A.215).

These rules streamline the criminal records check process for all of Oregon. They provide guidelines for decreasing risk to vulnerable populations from people who have access or provide care.

ODHS and OHA background check rules have been updated to follow DAS rules, while maintaining specific requirements needed for ODHS and OHA employees, contractors, volunteers, providers and qualified entities.

Keystroke technology is a software that tracks and collects data on employees’ computer use. It tracks each and every keystroke an employee types on their computer and is one of a few tools companies have to more closely monitor exactly how staff spend the hours they are expected to work.

Newer features allow administrators to also take occasional screenshots of employees’ screens.

One firm providing the tools is Interguard, which uses software allows administrators to view logs of employee computer use data, including desktop screenshots of employee activity. It also alerts administrators when certain employees’ computer activity diverts from their normal patterns.

Workplace surveillance is becoming the new normal for U.S. workers

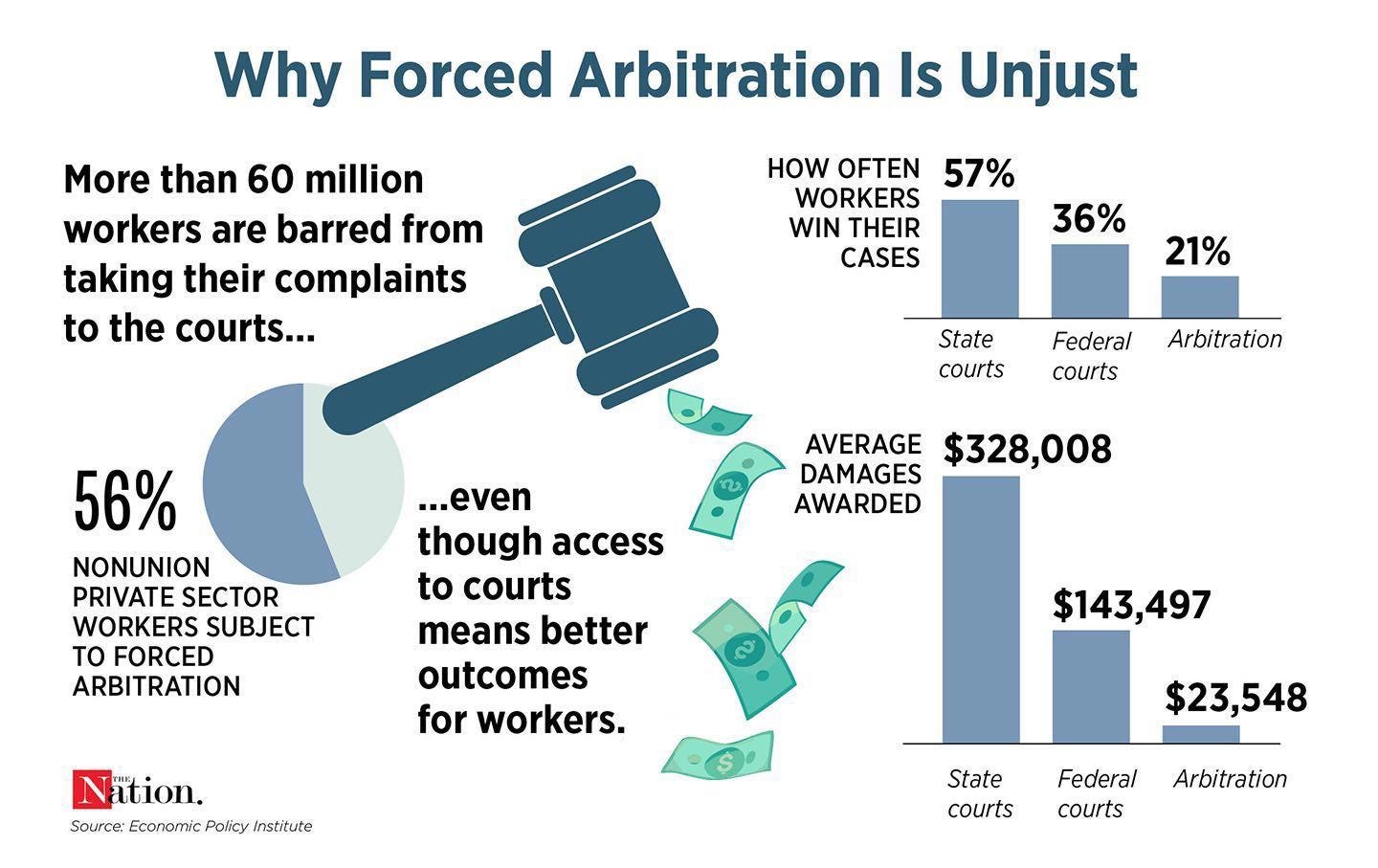

What is forced arbitration?

In forced arbitration, a company requires a consumer or employee to submit any dispute that may arise to binding arbitration as a condition of employment or buying a product or service. The employee or consumer is required to waive their right to sue, to participate in a class action lawsuit, or to appeal. Forced arbitration is mandatory, the arbitrator’s decision is binding, and the results are not public.

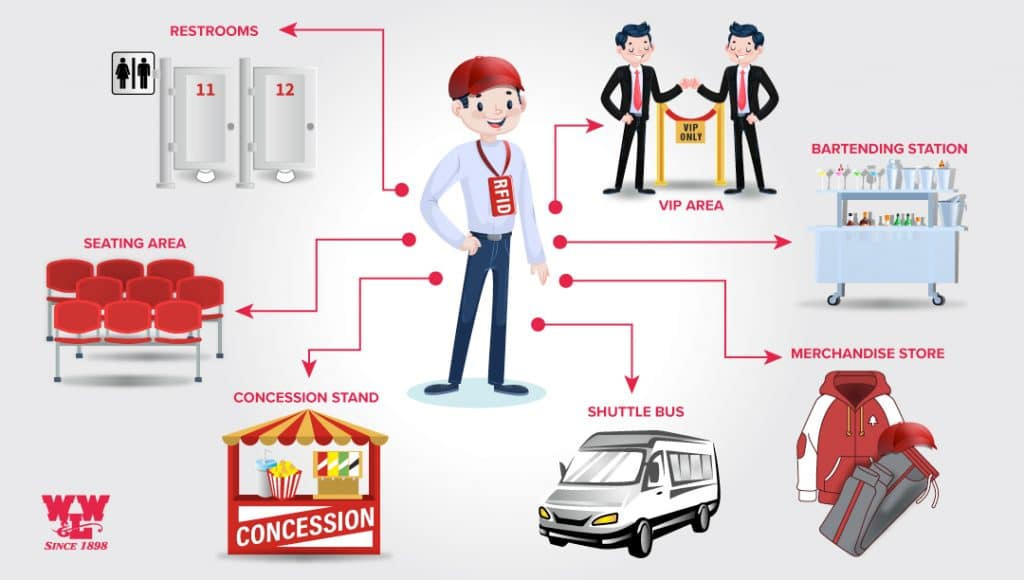

As more and more workplaces return to work in the next few months, these social distancing monitors are likely to become a minor boom industry of their own: Bloomberg News has reported that Ford planned to enforce social distancing by having its workers wear RFID wristbands, developed by Radiant RFID, that would buzz when a worker got too close to a colleague and would also provide supervisors with alerts about employees who were congregating together in larger groups.

Another company, Guard RFID, published a blog post detailing how its technology could be used for “infection control in the workplace,” including through the use of wearable RFID tags that would “alarm when tagged individuals come within close proximity to each other.” (Guard RFID and Radiant both declined to comment on their ventures into social distancing solutions.)

“A lot of tracking of workers happens under the rubric of worker safety or ensuring that workers are not injuring or hurting themselves,” she said. “But the boundaries between that and using the data in ways that are punitive or negative are hard to establish.”

A Wisconsin company is offering to implant tiny radio-frequency chips in its employees – and it says they are lining up for the technology.

The idea is a controversial one, confronting issues at the intersection of ethics and technology by essentially turning bodies into bar codes. Three Square Market, also called 32M, says it is the first U.S. company to provide the technology to its employees.

The company manufactures self-service “micro markets” for office break rooms. It said in a press release that obtaining a chip is optional, but expects that about 50 employees will take part.

CEO Todd Westby said that the company believes the technology will soon be ubiquitous:

“We foresee the use of RFID technology to drive everything from making purchases in our office break room market, opening doors, use of copy machines, logging into our office computers, unlocking phones, sharing business cards, storing medical/health information, and used as payment at other RFID terminals. Eventually, this technology will become standardized allowing you to use this as your passport, public transit, all purchasing opportunities, etc.”

The state laws on social media passwords are intended to protect social media pages that applicants have chosen to keep private. If you have publicly posted information about yourself without bothering to restrict who can view it, an employer is generally free to view this information. However, employers still need to follow other employment rules.

Antidiscrimination laws. An employer who looks at an applicant’s Facebook page or other social media posts could well learn information that it isn’t entitled to have or consider during the hiring process. This can lead to illegal discrimination claims. For example, your posts or page might reveal your sexual orientation, disclose that you are pregnant, or espouse your religious views. Because this type of information is off limits in the hiring process, an employer that discovers it online and uses it as a basis for hiring decisions could face a discrimination lawsuit.

Your Free Speech Rights (Mostly) Don’t Apply At Work

A noncompete agreement is a contract that an employer can use to prevent employees from taking certain jobs with competitors after they leave the company. Sometimes, an employer can make signing a non-compete agreement a condition of employment. These contracts benefit a company by preventing former employees from using trade secrets to give another company a competitive advantage or starting a company that competes with a former employer.

A noncompete agreement can also be referred to as a covenant not to compete, a noncompete covenant, a noncompete clause, or simply a noncompete.

+—+

The Man With the Stolen Name: They know what he did. They just don’t know who he is.

“John Doe,” of Owego, New York, was sentenced today to 57 months in prison for aggravated identity theft and misuse of a social security number. Doe used the name, social security number and date of birth of a homeless U.S. Army veteran to fraudulently obtain $249,811.93 in Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits and an additional $588,645.85 in state benefits. Doe’s true identity has yet to be confirmed.

The announcement was made by United States Attorney Carla B. Freedman and Gail. S. Ennis, Inspector General for the Social Security Administration (SSA).

United States Attorney Carla B. Freedman stated: “We don’t yet know the defendant’s name, but we know what he did. Today’s sentence justly punishes him for stealing the identity of a homeless veteran to fraudulently obtain hundreds of thousands of dollars in government benefits. Thanks to the collaborative efforts of local, state and federal investigators, we were able to bring John Doe to justice in spite of not knowing his true identity.”

SSA Inspector General Gail S. Ennis stated: “This individual stole the identity of a U.S. Army veteran to fraudulently obtain Supplemental Security Income benefits, a critical safety net for those in need. This sentence holds him accountable for his unlawful actions. My office will continue to pursue those who steal another person’s identity and misuse a social security number for personal gain. I appreciate the work of our law enforcement partners in this complex investigation and I thank Assistant U.S. Attorneys Adrian S. LaRochelle and Michael Gadarian for prosecuting this case.”

Doe was found guilty following a 4-day trial in May 2022. The evidence established that from approximately 1999 until June 2021, Doe received SSI benefits under the name, date of birth, and Social Security number of a homeless U.S. Army veteran living in North Carolina. When Doe’s use of the veteran’s identity was ultimately discovered and Doe was questioned by federal agents, Doe continued to falsely claim the identity as his own and provided agents with a photocopy of the victim’s birth certificate and Social Security card, claiming these documents were his own. Agents located the veteran and established through fingerprint and DNA analysis that Doe is not the person he claims to be.

United States District Judge Mae A. D’Agostino also ordered Doe to serve a 3-year term of supervised release following his release from prison and ordered Doe to pay a total $838,457.78 in restitution in connection with the benefits he unlawfully received under the victim’s name.

This case was investigated by the Social Security Administration Office of the Inspector General, the Tioga County Sheriff’s Office, the Tioga County Department of Social Services, and the New York State Police, with assistance provided by the U.S. Marshals Service. The case was prosecuted by Assistant U.S. Attorneys Adrian S. LaRochelle and Michael D. Gadarian.

WE ARE WITNESSES — The American criminal justice system consists of 2.2 million people behind bars, plus tens of millions of family members, corrections and police officers, parolees, victims of crime, judges, prosecutors and defenders. In We Are Witnesses, we hear their stories.

Early one summer morning, Son Yo Auer, a Burger King employee in Richmond Hill, Georgia, found a naked man lying unconscious in front of the restaurant’s dumpsters. It was before dawn, but the man was sweating and sunburned. Fire ants crawled across his body, and a hot red rash flecked his skin. Auer screamed and ran inside. By the time police arrived, the man was awake, but confused. An officer filed an incident report indicating that a “vagrant” had been found “sleeping,” and an ambulance took him to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Savannah, where he was admitted on August 31, 2004, under the name “Burger King Doe.”

Other than the rash, and cataracts that had left him nearly blind, Burger King Doe showed no sign of physical injury. He appeared to be a healthy white man in his middle fifties. His vitals were good. His blood tested negative for drugs and alcohol. His lab results were, a doctor wrote on his chart, “surprisingly within normal limits.” A long, unwashed beard and dirty fingernails suggested he had been living rough. But the only physical signs of previous trauma were three small depressions on his skull and some scars on his neck and his left arm.

We live in an age of extraordinary surveillance and documentation. The government’s capacity to keep tabs on us—and our capacity to keep tabs on each other—is unmatched in human history. Big Data, NSA wiretapping, social media, camera phones, credit scores, criminal records, drones—we watch and watch, and record our every move. And yet here was a man who appeared to exist outside all that, someone who had escaped the modern age’s matrix of observation.

His condition—blind, nameless, amnesiac—seemed fictitious, the kind of allegorical affliction that might befall a character in Saramago or Borges.

Even if he was lying about his memory loss, there was no official record of his existence. He lived on the margins, beyond the boundaries mapped by the surveillance state. And because we choose not to look at individuals on the margins, it is still possible for them to disappear.