One night in 1997, as Americans were parked on the couch in front of an episode of Touched by an Angel, they were touched by something else unexpected: an ad for a prescription allergy pill called Claritin®, promoted directly to the consumer!

One night in 1997, as Americans were parked on the couch in front of an episode of Touched by an Angel, they were touched by something else unexpected: an ad for a prescription allergy pill called Claritin®, promoted directly to the consumer!

Prescription drugs had never been sold directly to the public before, because, without a doctor’s recommendation, how could people know if the medication was appropriate or safe? Soon, ads for Xenical®, Meridia®, Propecia®, Paxil®, Prozac®, Vioxx, Viagra®, Singulair®, Nasonex®, Allegra®, Flonase®, Pravachol®, Zyrtec®, Zocor®, Flovent®, and Lipitor® followed. By 2006, the pharmaceutical industry (a.k.a. Pharma) was spending $5.5 billion a year on direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising—as much as the US government was spending for an entire month on the Iraq War.”

Although DTC advertising was never illegal, according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), it was widely thought to be until the FDA issued guidelines for advertisers in 1997. A push for DTC advertising also came from AIDS patients who wanted greater involvement in their own care and to know what their doctors knew about the drugs they were taking. But, a funny thing happened as Americans viewed all these pill ads. People discovered they weren’t as healthy as they thought.

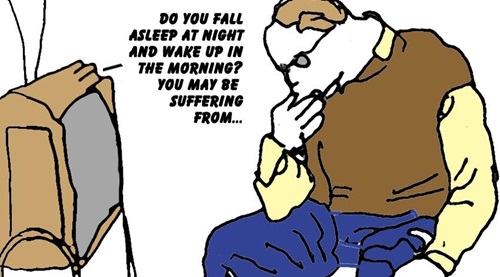

Suddenly, ad viewers suffered from seasonal allergies, social anxiety, high cholesterol, depression, bipolar disorder, ADHD, erectile dysfunction, low testosterone, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), irritable bowel syndrome, dry eye, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, seasonal affective disorder (SAD), restless legs syndrome, and worse. In fact, the parade of symptoms and diseases was so all encompassing, comedian Chris Rock said he was ready for a DTC ad asking, “Do you fall asleep at night and wake up in the morning?”

“Yeah, I got that!” he joked.

Before the advent of DTC advertising, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, was a hidden “epidemic” and often just heartburn and poor eating. But DTC advertising vaulted the condition vaulted to make Nexium® to the fourth-bestselling drug in the country by 2012.

“The implication in the direct-to-consumer ads is if you have heartburn you’re well on your way to cancer of the esophagus,” said Marcia Angell, MD, a former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine and author of The Truth about the Drug Companies. “For most people who have heartburn, the best way to treat it is probably to lose a little weight, get out and take a walk or drink a glass of milk, but that somehow is seen as less good than taking a prescription drug.”

The fact that DTC advertising debuted at the same time as the World Wide Web doubled its power. Even if ads and websites weren’t advertising drugs directly to consumers, the world of diseases and prescription drugs, once tucked into medical journal ads, was suddenly open to anyone who could operate a mouse. You could even buy drugs online, no doctor or prescription necessary.

Theoretically, all the newly and readily available medical information created a better-informed patient. It was the same reason the trailblazing feminist book Our Bodies, Ourselves was published thirty years earlier—patients have the right to know and be participants in their own healthcare. But three features of DTC advertising did more harm than good—unless you were Pharma.

Diseases were created or overplayed, sometimes called disease du jours. Risks of disease—fears of getting a condition or the condition getting worse—were whipped up to sell drugs. And extreme drugs were marketed when milder and cheaper drugs would do. The best example of this last point is Vioxx, which was billed as a “super-aspirin” for everyday arthritic or menstrual pain but ended up causing twenty-seven thousand heart attacks and sudden cardiac deaths before its removal from the market in 2004.29 Yet before Merck even settled the Vioxx cases, the dangerous epilepsy drugs Lyrica®, Topamax®, Neurontin, and Lamictal® and the antidepressant Cymbalta® were similarly marketed for simple pain, even though all carried suicide warnings and Topamax is also linked to birth defects. Finally, as drug advertisers became a major revenue stream for new media, news about drug risks, harms, deceptive marketing and high prices vanished overnight. Why bite the hand that feeds you?

It was obvious that no lessons had been learned from the Vioxx debacle which cost thousands of lives over 20 years ago.