Below, for the local newspaper, the Newport News Times. (without the images, etc.) Below that, more on this reprehensible genocidal black death Black Friday day!

The First No-Thanks Thanksgiving

Trigger Warning (noun): a statement at the start of a piece of writing, video, etc., alerting the reader or viewer to the fact that it contains potentially distressing material

This hoopla around Turkey Day — this so-called Big Box Store Shuffle and Great American Pig-out Thanksgiving — is a National Day of Mourning.

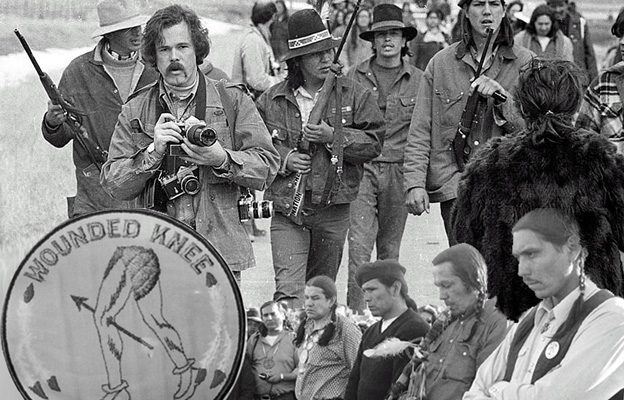

I was not my history teacher’s favorite student in high school when I wrote essays on my country’s hypocrisy of football, apple pie and Thanksgiving while never facing the genocide against the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island. I was called a traitor, self-loathing white and un-American when I pointed out the war against the “Indians” didn’t officially end until 1924, more than thirty years after the massacre at Wounded Knee (1890).

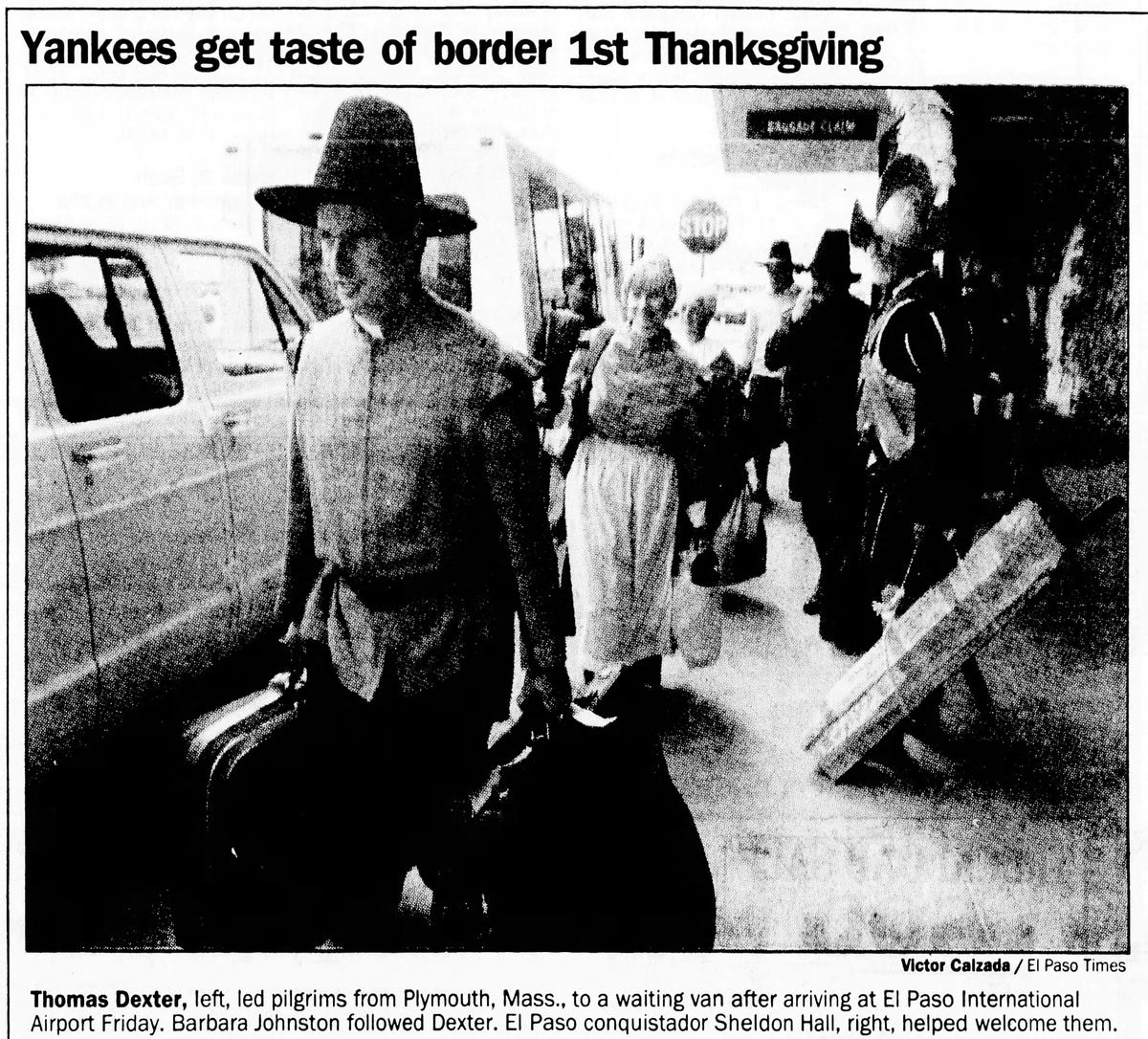

When I was teaching in El Paso, I got mired in a push to commemorate the “first” thanksgiving here, in Paseo del Norte. El Paso laid claim to the first undocumented/illegal settlement in North America in the form of Conquistadors and Friars.

In 1598 the Spanish explorer, Don Juan de Oñate, and his army established the first European colony in North America. The settlement was located at San Gabriel near Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, 30 miles north of Santa Fe.

I’ve been there, and the double-edge sword of breaking bread and pavo (turkey) with the Spanish interlopers is quaint for the people of El Paso looking for tourism bucks.

However, like the Plymouth Rock celebration of 1621, this Texas one represents a foreboding of genocide. I’ve been to that “celebration.” This El Paso organization declared this first Thanksgiving took place, near San Elizario, Texas. Oñate and his battalion of soldiers, Franciscan missionaries and colonists, celebrated their safe arrival on April 30, 1598.

That same year, the Spanish colonial governor de Oñate put 507 Acoma on trial. Women between 12 and 25 were enslaved for 20 years at the Pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh. Men over age of 25 had one foot cut off, and younger men were enslaved for 20 years. Oñate was later tried for excessive cruelty.

Switching to my Canadian roots, I absorbed more revised history. As a kid, I learned of that country’s treatment of Indigenous peoples since my mother was a journalist in Vancouver who reported on stories about Canada’s maltreatment of their First Nations. On September 30, 2021 Canada established a statutory holiday observation of Orange Shirt Day. This is a remembrance of missing and murdered children from residential schools as well as a process of healing for survivors.

It’s sort of a truth and reconciliation moment to raise consciousness about the residential school system and its impact on Indigenous communities for over a century. Hundreds of children were buried in unmarked graves at just one residential site, where my sister lived, Kamloops, BC. Thousands of other graves are located throughout Canada.

Then, in my Arizona high school days, I was “adopted” by some Apache friends and their families. Starting then – as their aunties and uncles were active in the American Indian Movement and Red Nation – I’d been to various events decrying the Plymouth Rock myth. For me, since age 15, Thanksgiving has been a Day of Mourning for Indigenous Peoples who were devastated by settler colonialism and imperialism.

The National Day of Mourning protest was founded by Wamsutta Frank James, an Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribal member, and other Indigenous men and women. In 1970, Wamsutta had been invited by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to speak at a banquet commemorating the 350th anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrims. The organizers of the banquet thought Wamsutta might deliver an honorific tribute singing the praises of the American settler colonial project. He was not about to “thanks” the Pilgrims for bringing “civilization” to the Wampanoag.

The speech that Wamsutta wrote, which was based on historical fact instead of the hollow fiction, portrayed in the Thanksgiving myth asked fundamental questions: What are the foundational myths of the United States? Who created them and who is erased and harmed?

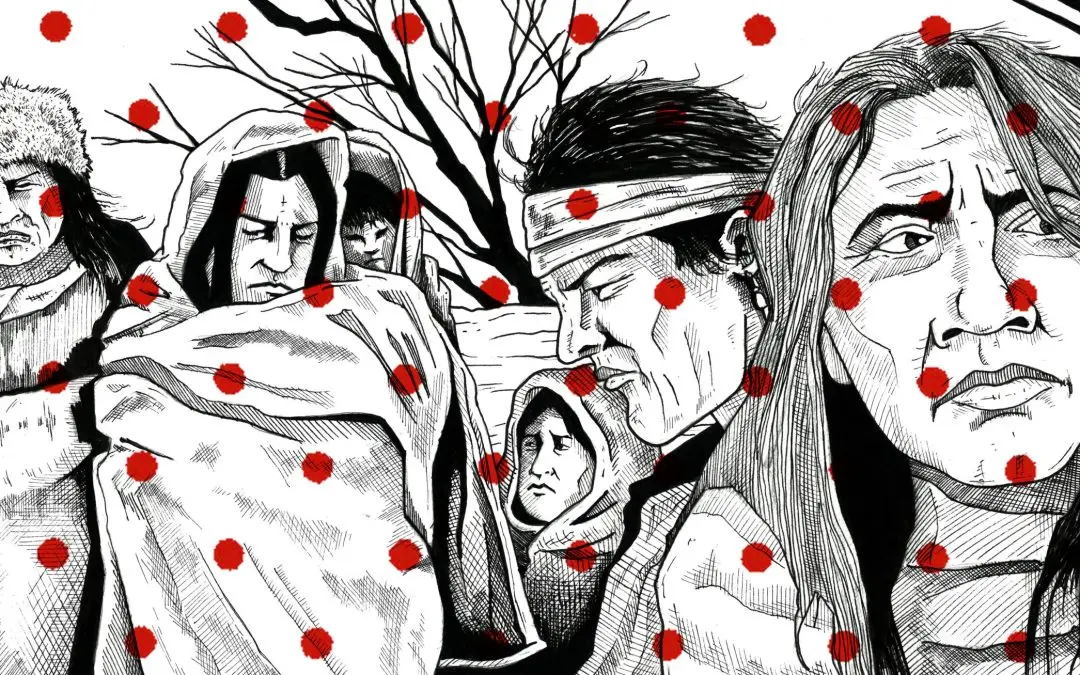

He detailed how the English before 1620 brought diseases that caused a “Great Dying.” They took Wampanoag people captive, selling them as slaves in Europe for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims robbed Wampanoag graves immediately upon landing in Massachusetts. Yes, there was a meal provided largely by the Wampanoag in 1621, but it was not a “thanksgiving.” Rather, the first official “thanksgiving” (not including the San Elizario one) was declared by the Puritans (not the Pilgrims) in 1637 to celebrate massacring hundreds of Pequot men, women and children on the banks of the Mystic River in Connecticut.

When the organizers of the celebration read the speech, they suppressed it. One of the more powerful messages in it was a collective message of Native American pride: “Our spirit refuses to die,” wrote Wamsutta. “Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting… We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we’ll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us.” (RIP, James, an elder of great weight)

Much of these histories – massacres of women and children, the enslavement of men, the amputation of feet, and the death of children ripped from families and forced into these “schools” – cannot be taught in K12, as there are no “trigger warnings” strong enough to “protect” youth from the truth. I’ve had young people complain to administrators for the negative and horrific stories a substitute brings to the high school class.

Going back to mythologies and Disneyfied presentations of history is not just retrograde; it’s dangerous. Having faculty like myself being charged with “teaching anti-white critical race theory junk” is also McCarthyite.

Thank goodness for some of my activist friends in El Paso who years ago did some statue editing: they chopped off the bronze foot of Don Onate as he is poised on a Spanish steed high above his slaves. The foot has never been found.

Part Two

Amazing curriculum,

The revised edition of Native People of Wisconsin introduces students to the historical background, cultural traditions, and treaties negotiated by the eleven federally-recognized Indian Nations in the state today, the Brothertown Indians, a group still waiting to regain federal recognition, and urban Indians. This is serious material, the only mandated subject in social studies instruction in Wisconsin.

Author Patty Loew is a member of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Ojibwe Nation, who based Native People of Wisconsin on the research done for Indian Nations of Wisconsin, now in its second edition, which is written for a general audience. She strongly feels the responsibility to help students gain knowledge of Indian Country from a Native perspective and from the perspective of each major tribal group represented in Wisconsin’s current population.

The authors of this accompanying teacher’s guide want you to feel confident and comfortable teaching about Native people even if you don’t have much firsthand knowledge. Of course, you and your students have been inundated with images of Indian people, and it’s important that you help your students separate the reality from the stereotypical or mythical, positive and negative. We are happy to direct instructors to real stories from Native communities in videos produced by The Ways: Stories on Culture and Language from Native Communities Around the Central Great Lakes. This online educational resource is a production of Wisconsin Media Lab. The videos are integrated into many of the activities we’ve included and are linked to their corresponding activities in the Table of Contents. Educators may use this video content in conjunction with these Student Activities: Learning from My Elders; Food That Grows on the Water; Oneida Language & Culture; Boarding Schools; Native Songs and Dances (source)

Yet, if this post were to be read by the same people reading my short piece, the one above, with the post’s title, “The First No-Thanks Thanksgiving,” which I hope will appear in the Newport News Times, what kind of backlash would I receive?

Tons of writers or bots or both calling me a kook or loony or anti-business or self-hating when I weigh in on various alternative news sites.

Bottom line is we need more nuance, more critical thinking, and more people who can be counter-intuitive and have several theses, sometimes contradictory, while holding onto strong ethical frame works. I can be for the Declaration of Human Rights, a la United Nations, but I can also be opposed to many of the UN’s programs, people, representatives.

I can see the amazing forward thinking of say The Earth Charter, but I can also think hard about systems, how we need more than a charter, and we need true communism with people power, planet power, thinking and acting globally but also living and organizing and doing locally and regionally.

How can we not engage positively with this?

We stand at a critical moment in Earth’s history, a time when humanity must choose its future. As the world becomes increasingly interdependent and fragile, the future at once holds great peril and great promise. To move forward we must recognize that in the midst of a magnificent diversity of cultures and life forms we are one human family and one Earth community with a common destiny. We must join together to bring forth a sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace. Towards this end, it is imperative that we, the peoples of Earth, declare our responsibility to one another, to the greater community of life, and to future generations.

Alas, though, any sort of collective and creative and earth and people centric thinking will be attacked. Any thinking around just what happened to Native Americans over the course of almost 600 years, that is not heretical.

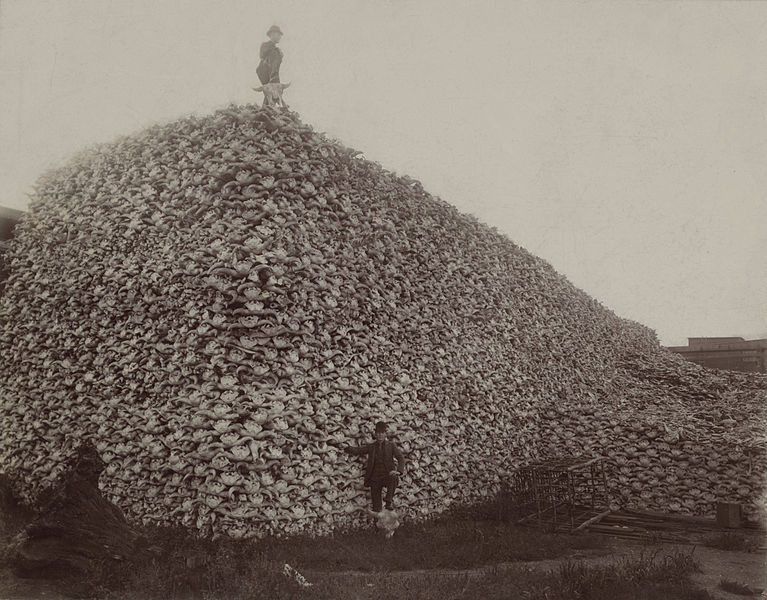

Just what was that Union Pacific Railroad all about? Mr. Durant, getting how many millions of acres for that transcontinental feat? How many millions of buffalo slaughtered — “shot from the comfort of your railcar” Indian Killing, err, Buffalo Killing, trips?

The telegram arrived in New York from Promontory Summit, Utah, at 3:05 p.m. on May 10, 1869, announcing one of the greatest engineering accomplishments of the century:

The last rail is laid; the last spike driven; the Pacific Railroad is completed. The point of junction is 1086 miles west of the Missouri river and 690 miles east of Sacramento City.

Back in Utah, railroad officials and politicians posed for pictures aboard locomotives, shaking hands and breaking bottles of champagne on the engines as Chinese laborers from the West and Irish, German and Italian laborers from the East were budged from view. (source)

Oh, that was General Sheridan’s concept of Total War, which he utilized heading to Atlanta: three hundred miles of immolated towns, farms, livestock, crops, everything. He now was with President Grant attempting to take care of the “Indian Problem.” Imagine that, more than 120 years ago, utilizing the concept of destroying great people like the Lakota using psychology as a weapon.

Harper’s Weekly described these hunting excursions:

Nearly every railroad train which leaves or arrives at Fort Hays on the Kansas Pacific Railroad has its race with these herds of buffalo; and a most interesting and exciting scene is the result. The train is “slowed” to a rate of speed about equal to that of the herd; the passengers get out fire-arms which are provided for the defense of the train against the Indians, and open from the windows and platforms of the cars a fire that resembles a brisk skirmish. Frequently a young bull will turn at bay for a moment. His exhibition of courage is generally his death-warrant, for the whole fire of the train is turned upon him, either killing him or some member of the herd in his immediate vicinity.

I just finished the eight-part series, The American West, a Robert Redford production. Jesse James, Billy the Kid, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Wyatt Earp, Custer. Durant is also a character in the dramatized documentary. Seeing John McCain yammering away about Indigenous peoples in this series takes some acid reflux pills, but then, Tom Selleck, and Kiefer Sutherland and Burt Reynolds?

Producers Stephen David and Tim Kelly:

What prompted you to explore the West in your latest series?

Stephen: We found that after the Civil War – the series focuses on the 25 years after the Civil War – the country was broken and divided, but 25 years later we wound up with this unified country with the same good-bad similarities going on throughout the country. Big business ran things. The American spirit that we have today came from this 25-year period. The lawman, the outlaws, the Army, the Native Americans – everything that was mixed up in this time period – contributed to who we are today.

Tell us what we can expect from the episodes.

Tim: You can expect an unknown story of the West and how the West was settled. It’s a lot of names that you know with a lot of unknown stories. You’ll see the way everything was connected and how the push West was shaped by the Civil War and the opportunity that was available. It’s a very personal story. It focuses on a group of people who aren’t necessarily directly connected, but the effect of what they do is seen throughout the West and how it is formed. There’s also focus on the Native Americans. It’s a mix of outlaws, politicians and Native Americans and the roles they played settling the West.

Yeah, I was a reporter in Tombstone, for the University of Arizona lab paper, The Tombstone Epitaph. I then was a graduated BA/BS working in Bisbee, Cochise County and along the border on both sides of the dividing line.

I was a reporter and teacher and activist in El Paso, and Las Cruces, and had tequila and empanadas on the grave of John Wesley Hardin in Concordia Cemetery.

In the mix, of course, with all these documentaries and dramas the Native Americans are either completely washed out of these stories, or set into a white man’s milieu. I’ve studied graduate courses on “planning in the West,” you know, urban and regional planning. Looking at the West as a unique place in the USA, with a large chunk of the planning course looking at water, Indian sovereignty, and more.

“One cannot be pessimistic about the West. This is the native home of hope. When it fully learns that cooperation, not rugged individualism, is the quality that most characterizes and preserves it, then it will have achieved itself and outlived its origins. Then it has a chance to create a society to match its scenery.”

Boom and bust, the West. In 2022, the West is all about sinking and shrinking waterways and reservoirs and fires and population influxes and the same snake oil salesmen I ran into in Tucson and throughout Arizona, New Mexico and West Texas.

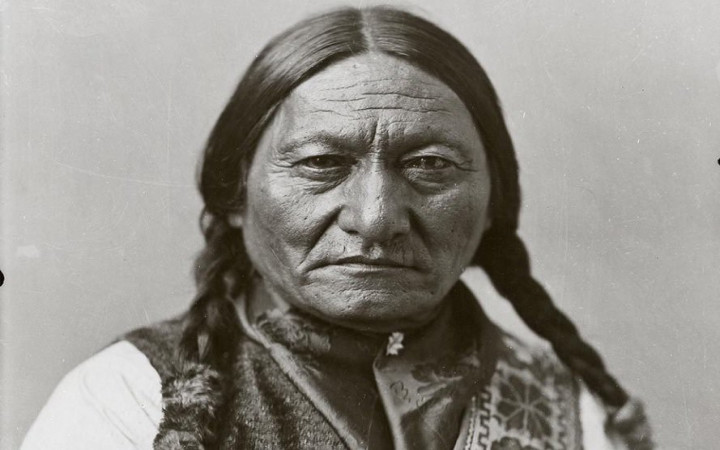

I am a red man. If the Great Spirit had desired me to be a white man he would have made me so in the first place. He put in your heart certain wishes and plans, in my heart he put other and different desires. Each man is good in his sight. It is not necessary for Eagles to be Crows.

–Sitting Bull, Hunkpapa Lakota chief. God Is Red: A Native View of Religion by Vine Deloria

They want us to give up another chunk of our tribal land. This is not the first time or the last time. They will again try to gain possession of the last piece of ground we possess.

— Sitting Bull, speech against Sioux Bill of 1889