Orientation

Over the last three hundred years in the West, nationalism has supplanted religious, regional, ethnic and class loyalties to claim a secular version of the commandment “I am the Lord thy God, thou shalt not have strange gods before me”. How did this happen? Let’s say we have an Italian-American member of the working-class who lives in San Francisco. How is it possible that this person is expected to feel more loyalty to a middle-class Irishman living in Boston compared to Italians living in Milan, Italy? How is it that this loyalty is so great that this Italian-American would risk his life in the military against the same Italian in Milan in the case of a war between the United States and Italy? Why would the same working-class man kill and/or die in a battle with Iraq soldiers who were also working class? My article attempts to explain how people were socialized in order to internalize this nationalistic propaganda. Nationalism used the paraphernalia of a particular kind of religion, monotheism, to command such loyalty. This article is a synthesis of part of my work in chapters two and three of my book, Forging Promethean Psychology.

Questions about nationalism, nations, and ethnicity

Nationalism is one of those words that people immediately feel they understand, but upon further questioning, we find a riot of overlapping and conflicting elements. There are three other words commonly associated in the public mind with nationalism and used interchangeably with it: nation, state, and ethnicity. The introductions of these terms raise the following provocative questions:

- What is the relationship between nationalism and nations? Were there nations before nationalism? Did they come about at the same time or do they have separate histories? Can a nation exist without nationalism? Can nationalism exist without a nation? Ernest Gellner (Nations and Nationalism) thinks so.

- What is the relationship between a state and a nation? Are all states nations? Are all nations states? Can states exist without nationalism?

- What is the relationship between ethnicity and a nation? Can one be part of an ethnic group and not have a nation? Can one be a part of a nation without being in an ethnic community?

There is rich scholarly work in this field and most agree that nations, nationalism, ethnicities, and states are not interchangeable. Despite scholars’ differences about the questions above, they agree that nationalism as an ideology that arose at the end of the 18th century with the French Revolution. Because our purpose is to understand nationalism as a vital component in creating loyalty we are, mercifully, on safe ground to limit our discussion to nationalism.

Elements of Nationalism

Four sacred dimensions of national identity

In his wonderful book Chosen Peoples, Anthony Smith defines nationalism as an ideological movement for the attainment and maintenance of three characteristics: autonomy, unity, and identity. Nationalism has elite and popular levels. Elite nationalism is more liberal and practiced by the upper classes. Popular nationalism is more conservative and practiced by the lower classes. According to Smith, the four sacred foundations for all nations are (1) a covenant community, including elective and missionary elements; (2) a territory; (3) a history; and (4) a destiny.

The fourth sacred source of nationalism – destiny – is a belief in the regenerative power of individual sacrifice to serve the future of a nation. In sum, nationalism calls people to be true to their unique national vocation, to love their homeland, to remember their ancestors and their ancestors’ glorious pasts, and to imitate the heroic dead by making sacrifices for the happy and glorious destiny of the future nation.

Core doctrine of nationalism

These four dimensions of sacred sources in turn relate to the core doctrine of the nation, which Smith describes as the following:

- The world is divided into nations, each with its own character, history and destiny.

- The source of all political power is the nation, and loyalty to the nation overrides all other loyalties.

- To be free, every individual must belong to a nation.

- Nations require maximum self-expression and autonomy.

- A world of peace and justice must be founded on free nations.

Phases of nationalism

Most scholars agree that nations are a necessary but insufficient criterion for nationalism. While most of them agree that nationalism did not arrive until the end of the 18th century, almost all agree with the following phases of nationalism:

- Elite nationalism—This first nationalism emerged when the middle classes used language studies, art, music, and literature to create a middle-class public. The dating of this phase varies depending on the European country and ranges from the Middle Ages through the early modern period.

- Popular nationalism—A national community took the place of the heroes and heroines who emerged with the French Revolution. This nationalism was political and was associated with liberal and revolutionary traditions. This phase is roughly dated from 1789 to 1871.

- Mass nationalism—This nationalism was fueled by the increase in mass transportation (the railroad) and mass circulation of newspapers. It also became associated with European imperialism and argued that territory, soil, blood, and race were the bases of nationalism. This last phase of nationalism was predominant from 1875 to 1914.

In the second and third phases of nationalism, rites and ceremonies are performed with an orchestrated mass choreography amidst monumental sculpture and architecture (George Mosse, The Nationalization of the Masses)

Due to the Industrial Revolution, among other things, individualists began to sever their ties to ethnicity, region, and kinship group as capitalism undermined these identities. By what processes were these loyalties abandoned while a new loyalty emerged? The new loyalty is not based on face-to-face connections, but rather it was mediated by railroads, newspapers and books. This is a community of strangers whose loyalty to the nation is not based on enduring, face-to-face engagements. As we shall see, states create nationalism by two processes: first by pulverizing the intermediate relationships between the state and the individual and second by bonding individualists to each other through loyalty to the nation forged by transforming religious techniques into secular myths and rituals.

Centralized State Against Localities and Intermediate Organizations

Absolutist states in Europe didn’t emerge out of nothing. According to Tilly, they emerged out of kingdoms, empires, urban federations, and city-states and had to compete with them for allegiance. In feudal times, local authorities could match or overwhelm state power. This slowly changed as the state centralized power.

In their battles against these other political forms, states learned hierarchical administration techniques from churches that had hundreds of years of experience.

Churches held together the sprawling kingdoms of Europe, beginning with the fall of the Roman Empire and throughout the early, central, and high Middle Ages. In order to command obedience, the absolutist state had to break down the local self-help networks that had developed during the feudal age and among those states that became empires. What stood in the way of state centralization were the clergy, landlords, and urban oligarchies who allied themselves with ordinary people’s resistance to state demands.

Dividing and conquering intermediaries

Early modern popular allegiances of culture, language, faith, and interests did not neatly overlap with centralized political boundaries. States played a leading role in determining who was included and who was excluded in their jurisdictions. This would force people to choose whether they wanted to live in a state where they would, for example, become a religious or cultural minority. Furthermore, the state can play its cultural, linguistic, and religious communities against one another by first supporting one and then switching to support another.

It may seem self-evident that absolutist states would try to join and expand whatever local identity a people had, such as the Basques or the Catalans in Spain. However, this was not initially the case. A local identity was interpreted as a threat just like any other non-state identity—region, ethnic group, or federation—because it competed with the state for people’s loyalty. It was only later when states were out of cash and desperate for manpower that they began trying to manipulate these outside loyalties by promising citizenship and later education in exchange for taxes and conscription.

Sociologists and social psychologists have demonstrated that among a group with internal conflicts, the best way to get them to forge unity is to present them with a common group enemy. An individual’s group loyalty is solidified by discrimination against an outside group. Most often a scapegoat is selected because it is present, visible, powerless to resist, and useful for displacing aggression.

Building a centralized nervous system: postal networks and newspapers

States reduced barriers between regions by developing roads and postal systems. In the late medieval world, the emergence of private mercantile networks enabled postal communication to form. In the 15th and 16th centuries, private postal networks were built. In France, the postal system was created as early as the late 1400s, and in England it came about in 1516. They expanded until they linked much of Europe together, employing 20,000 couriers. Turnpike construction upgraded routes from major centers to London. From the second half of the 18th century on the postal network offered regular service between regions as well as into London. By 1693 in the United States regular postal service connected Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, and the comprehensive postal network assured postal privacy. The network of US postal systems came to exceed that of any other country in the world and was a way to bring the Western frontier under the umbrella of the Northern industrialists in their struggle against the agricultural capitalists of the South.

Postal networks also supported the creation of news networks intended for bankers, diplomats, and merchants. They contained both the prices of commodities on local markets and the exchange rates of international currencies. Newspapers also helped centralize and nationalize American colonies by pointing to commonalities across regions. For example, the Stamp Act led to the first inter-colonial cooperation against the British and the first anti-British newspaper campaign.

State vs. Religion Conflicts

In spite of what they learned from ecclesiastical hierarchies about organization, the state and the Catholic church were opposed to each other. The church was an international body that had a stake in keeping any state from competing with it for power. Before the alliance between merchants and monarchs, the Catholic Church played states off of one another. One event that began to reverse this trend was the Protestant Reformation. Protestant reformers may not have been advocates for the national interests of Germany, Switzerland, Holland, or England per se, but they were against the international aspirations of the Catholic church. Protestant leaders like Wycliffe and Hus called for the use of vernacular (local language) rather than internationalist Latin in religious settings. The Protestant religions became increasingly associated with either absolute monarchies or republics (e.g., the Dutch).

Religious Roots of Nationalism

What is the relationship between nationalism and religion?

It is not enough for states to promise to intervene in disputes and coordinate the distribution and production of goods, although this is important. Bourgeois individualists must also bond emotionally with each other through symbols, songs, initiations, and rituals. In this effort, the state does not have to reinvent the wheel. There was one social institution prior to the emergence of absolutist states that was also trans-local and trans-regional. Interestingly, this institution also required its members to give up their kin, ethnic identity, and regional identity in order to become full members. That institution was religion. A fair question to ask is, what is the relationship between religion and nationalism?

Do religion and nationalism compete with each other? Do they replace each other? Do they amplify each other and drive each other forward? Do they exist in symbiosis? Theorists of nationalism have struggled with this question. At one extreme of the spectrum is the early work of Elie Kedourie (1960), who argued that nationalism is a modern, secular ideology that replaces religious systems. According to Kedourie, nationalism is a new doctrine of political change first argued for by Immanuel Kant and carried out by German Romantics at the beginning of the 19th century. In this early work, nationalism was the spiritual child of the Enlightenment, and by this we mean that nationalism and religion are conceived of as opposites. While religion supports hierarchy, otherworldliness, and divine control, nationalism, according to Kedourie, emphasizes more horizontal relationships, worldliness, and human self-emancipation. Where religion supports superstition, nationalism supports reason. Where religion thrives among the ignorant, nationalism supports education. For Enlightenment notions of nationalism, nationalism draws no sustenance from religion at all.

Modern theorists of nationalism such as Eric Hobsbawm (Nations and Nationalism since 1780) and John Breuilly, (Nationalism and the State) share much of this position. For these scholars, secular institutions and concepts such as the state or social classes occupy center stage, while ethnicity and religious tradition are accorded secondary status. For Liah Greenfeld (Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity), religion served as a lubricator of English national consciousness until national consciousness replaced it.

For Anthony Smith, nationalism secularized the myths, liturgies, and doctrines of sacred traditions and was able to command the identities of individualists not only over ethnic, regional, and class loyalties, but even over religion itself. What Smith wants to do is conceive of the nation as a sacred communion, one that focuses on the cultural resources of ethnic symbolism, memory, myth, values, as they are expressed in texts, artifacts, scriptures, chronicles, epics, music, architecture, painting, sculpture, and crafts. Smith’s greatest source of inspiration was George Mosse who discussed civic religion of the masses in Germany.

How the State Uses Religious Paraphernalia in the French Revolution

If we examine the process of how the state commands loyalty, we find the state uses many of the same devices as religion. After the revolution in France, the calendar was changed to undermine the Catholic church. The state tried to regulate, dramatize, and secularize the key events in the life of individual—birth, baptism, marriage and death. French revolutionaries invented the symbols that formed the tricolor flags and invented a national anthem, “La Marseillaise.” The paintings of Delacroix and Vermeer supported the revolution. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen became a new belief system, a kind of national catechism. By 1791 the French constitution had become a promise of faith. The tablets of the Declaration of Rights were carried around in procession as if they were commandments. Another symbol was the patriotic altar that was erected spontaneously in many villages and communes. Civic festivities included resistance to the king in the form of the famous “Tennis Court Oath,” (Serment du Jeu de Paume) along with revolutionary theater. The revolution, through its clubs, festivals, and newspapers, was indirectly responsible for the spread of a national language. Abstract concepts such as fatherland, reason, and liberty became deified and worshipped as goddesses. All the paraphernalia of the new religion appeared: dogmas, festivals, rituals, mythology, saints, and shrines. Nationalism has become the secular religion of the modern world, where the nation is now God.

What occurs is a reorganizing of religious elements to create a nation-state, a social emulsifier that pulverizes what is left of intermediate organization while creating a false unity. This state unity papers over the economic instabilities of capitalism as well as the class and race conflicts that it ushers in.

Monotheistic Roots of Nationalism

How monotheism differs from animism and polytheism

Anthony Smith is not simply saying that religion itself is the foundation of nationalism. He claims that the monotheism of Jews and Christians forms a bedrock for European nationalism. However, Smith does not account for why animistic and polytheistic religious traditions are not instrumental in producing nationalism. What are the sacred differences between magical traditions of tribal people and monotheists? The high magical traditions of the Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Aztecs, and Incas are not much like the Jews and Christians. We need to understand these religious differences so we can make a tighter connection between monotheism and nationalism.

According to Smith, the foundation for the relationship between a monotheistic people and its God is a covenant. A covenant is a perceived voluntary, contractual sacred relationship between a culture and its sacred presences. This contractual relationship is one of the many differences that separates monotheism from polytheism and animism. In my book From Earth-Spirits to Sky-Gods, I show how polytheistic and animistic cultures perceive a necessary, organicconnection between themselves and the rest of the biophysical world, and this connection extends to invisible entities. The monotheistic Jews were the first people to imagine their spiritual relationships as a voluntary contract.

The first part of a covenant agreement is that God has chosen a group of people over all other groups for a particular purpose. This implies that God is a teleological architect with a plan for the world and simply needs executioners. Polytheistic and animistic people imagine their sacred presence as a plurality of powers that cooperate, compete, and negotiate a cosmic outcome having some combination of rhythm and novelty, rather than a guiding plan. Like Jews and Christians, pagan people saw themselves as superior to other cultures (ethnocentrism), but this is not usually connected up to any sense of them having been elected for a particular purpose by those sacred presences.

The third part of a covenant is the prospect of spreading good fortune to other lands. This is part of a wider missionary ideal of bringing light to other societies so that “the blind can see”. It is a small and natural step to affirm that the possession of might—the second part of the covenant (economic prosperity and military power)—is evidence that one is morally right. We know that the ancient Judaists sought to convert the Edomites though conquest. On the other hand, while it is certainly true that animistic and polytheistic people fight wars over land or resources, these are not religious wars waged by proselytizers.

The fourth part of a covenant is a sacred law. This is given to people in the form of commandments about how to live, implying that the natural way people live needs improvement. In polytheistic societies, however, how people act was not subject to any sort of a plan for great reform on the part of the deity. In polytheistic states, the gods and goddesses engaged in the same behavior as human beings, but on a larger scale. There was no obedience expected based on a sacred text.

The fifth part of a covenant is the importance of human history. Whatever privileges the chosen people have received from God can be revoked if they fail to fulfill their part of the bargain. The arena in which “tests” take place is human history, in the chosen people’s relationship with other groups. For the animistic and polytheists, cultural history is enmeshed with the evolutionary movement of the rocks, rivers, mountains, plants, and animals. There is no separate human history.

Lastly, in polytheistic societies, sacred dramas enacted in magical circles and temples were rituals. This means they were understood as not just symbolic, representational gestures of a reality that people wished to see in the future. Rather, they were dramatic actions believed to be real embodiments of that reality in the present. In the elite phase of monotheism in the ancient world, rituals were looked upon with suspicion because people became superstitiously attached to the ritual and thought their rituals could compel God to act. In From Earth Spirits to Sky Gods, I coined the word ceremony to describe sacred dramas that were more passive and less likely to create altered states of consciousness. These were intended to show deference and worship to a deity who was not subject to magical incantations. A religious ceremony, at least among middle and upper-middle class, is more passive. The priest or pastor does most of the work while the congregation supports what the priest or pastor is doing.

Common Elements Found in Monotheism and Nationalism

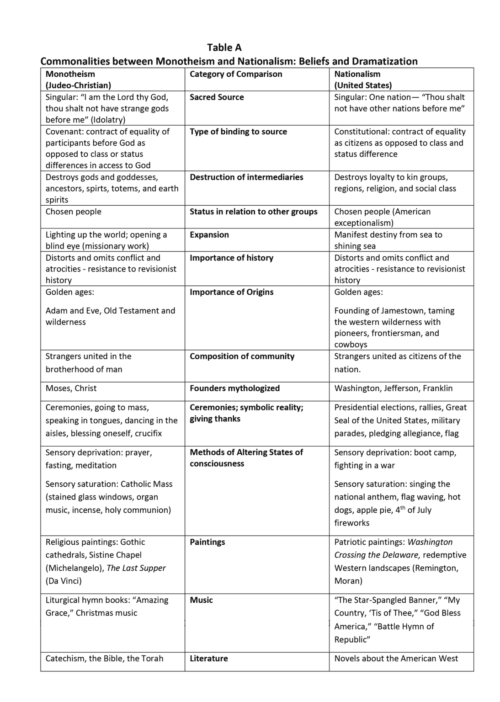

Let’s start with some definitions. Monotheism is a sacred system prevalent in stratified state societies with possible developing empires in which a single, abstract and transcendental deity presides over “chosen people” via a contract or covenant. Nationalism is a secular system which exists in capitalist societies in which a single nation claims territory regulated by a state. Before launching into a description of the commonalities, Table A provides a snapshot overview of where we are headed. Loyalty to one God; loyalty to one nation

Loyalty to one God; loyalty to one nation

All sacred systems have to answer the question of whether the sacred source of all they know is singular or plural. Monotheistic religions break with the pluralistic polytheism and animism of pagan societies and assert that there is only one God. It is not a matter of having a single god who subordinates other gods. This is not good enough. The very existence of other gods is intolerable. Any conflicting loyalties are viewed as pagan idolatry.

Just as monotheism insists on loyalty to one God, so nationalism insists on loyalty to one nation. Claiming national citizenship in more than one country is viewed upon with suspicion. Additionally, within the nation, loyalty to the nation-state must come before other collective identities such as class, ethnic, kinship, or regional groupings. To be charged with disloyalty to the nation is a far more serious offence than disloyalty to things such as a working-class heritage, an Italian background, or having come from the West Coast. In the case of both monotheism and nationalism, intermediaries between the individual and the centralized authorities must be destroyed or marginalized.

Loyalty to strangers in the brotherhood of man; loyalty to strangers as fellow citizens

The earth spirits, totems, and gods of polytheistic cultures are sensuous and earthy. In tribal societies, they are part of a network among kin groups in which everyone knows everyone else. The monotheistic God is, on the contrary, abstract, and the community He supervises an expanding non-kin group of strangers. Just as monotheism insists that people give up their ties to local kin groups and their regional loyalties, so the nation-state insists that people imagine that their loyalty should be to strangers, most of whom they will never meet. The universal brotherhood of man in monotheism becomes the loyalty of citizens to other citizens within the state. In monotheism, the only way an individual can be free is to belong to a religion (pagans or atheists are barely tolerated). In the case of a nation-state, to be free the individual must belong to a nation. The state cannot tolerate individuals with no national loyalty.

Many inventions and historical institutions facilitate one’s identifying with a nation. The invention of the printing press and the birth of reading and writing helped build relationships among strangers beyond the village. Newspapers and journals gave people a more abstract sense of national news, and they were able to receive this news on a regular basis. The invention of the railroad, electricity, and the telegraph expanded and concentrated transportation and communication.

The problem for nationalists is that all these inventions can also be used to cross borders and create competing loyalties outside the nation-state. Increasing overseas trade brought in goods from foreign lands and built invisible, unconscious relations with outside producers. In the 19th century, another connection between strangers began with the international division of labor between workers of a colonial power and workers exploited on the periphery.

Monotheistic contract of equality before God; constitutional contract of equal citizenship

In polytheistic high magical societies, it was only the upper classes who were thought to have a religious afterlife. If a slave was to have an afterlife at all, it would be as a servant to the elite. Monotheism democratized the afterlife, claiming that every individual, as part of God’s covenant agreement, had to be judged before God equally. So too, nationalism in the 18th century imagined national life as a social contract among free citizens, all of whom were equal in the eyes of the law and the courts of the nation. In the 19th and 20th centuries, popular nationalism included the right to vote in elections.

Monotheistic and nationalist history is repackaged propaganda

According to Anthony Smith, the history that religions construct is not the same as what the professional historians aspire to do. For example, historians ask open-ended questions for which they do not have answers. They accept the unknown as part of the discipline and accept that an unknown question may never be answered. In contrast, accounts of religious history are not welcoming to open-ended questions. Rather, they ask rhetorical questions for which they have predictable answers. Those believers or non-believers who ask open-ended questions are taught that the question is a mystery that will only be revealed through some mystical experience or in the afterlife. Further insistence on asking open-ended questions is viewed as blasphemy or a sign of heresy.

So too, nationalist renditions of history do not welcome open-ended, skeptical questions. The history books of any nation generally try to paper over actual struggle between classes, enslavement, colonization, and torture that litters its history. Members of a culture that have built nationalist histories like to present themselves as being in complete agreement about the where and when of their origins. But, in fact, evidence about the past often competes with each other and are often stimulated by class differences within the nation. Just as religion attacks open-ended, critical questions of heresy, so nationalists tar and feather citizens as unpatriotic when they question national stories and try to present a revisionist history.

Monotheistic and Nationalist History Is Cyclic

All national histories have a cyclical shape. They begin with a golden age and are followed by a period of disaster or degradation and, after much struggle, a period of redemption. First, there is a selection of a communal age that is deemed to be heroic or creative. There is praise for famous kings, warriors, holy men, revolutionaries, or poets. Second, there is a fall from grace, whether it be a natural disaster, a fall into materialism, or external conquest. Third, there is a yearning to restore the lost communal dignity and nobility. In order to return to the golden age, they must emulate the deeds and morals of its past epoch. For Christianity, the golden age consists of the story of Adam and Eve. For the Hebrews, it is the Old Testament with Moses in the wilderness. In the United States, it is the time of pilgrims, pioneers, frontiersman, cowboys, and Western expansion. These are mythic stories are endlessly recycled today in television program and movies.

Monotheist and Nationalist Founders Are Treated as Divine

Nationalist history is sanitized, polished, and presented as a result of the deeds of noble heroes. This mythology is intensified by the way the founders of religion and the nation are treated. It is rare that Moses, Christ, or Mohammad, in addition to their good qualities, are treated as flesh and blood individuals with weaknesses, pettiness, and oversights. So too, in the United States, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson are treated like Moses or Christ, having charismatic powers.

Monotheistic and nationalist altered states of consciousness

Altered states can be created by either sensory saturation or sensory deprivation. A great example of sensory saturation to create an altered state is the Catholic Mass. Here we have the bombardment of vision (stained glass windows), sound (loud organ music), smell (strong incense), taste (the holy communion), and touch (gesturing with the sign of the cross). Sensory deprivation in a monotheistic setting includes fasting, prayer, or meditation. Popular monotheistic states of consciousness invite speaking in tongues, and devotional emotional appeal.

Sensory deprivation in nationalistic settings is being at boot camp and on the battlefield of war itself. Sensory saturation occurs in nationalistic settings at addresses by prominent politicians, such as the presidential State of the Union addresses, in congressional meetings, at political rallies, and during primaries. Presidential debates and elections are actually throwbacks to ancient rituals and ceremonies. Those diehards of electoral politics who attend these rituals are almost as taken away by the props as were participants in a tribal magical ceremony. In the United States, the settings include the Great Seal of the United States hanging above the event, along with the American flag, a solemn pledge of allegiance, a rendition of “God Bless America,” and a military parade.

Religious and Nationalistic Attachment and Expansion of Land

The relationship between monotheism and territorial attachment is conflicted. On the one hand, elite monotheists in ancient times depreciated the importance of territorial attachment as an expression of pagans whom Christians feel are enslaved to the land. The prophets promote a kind of cosmopolitanism. Yet on the other hand, the more fundamentalist sects in popular monotheism insist on locating the actual birthplace of the religion and making it the scene of pilgrimages—Muslims go to Mecca, Christians to Bethlehem—or even a permanent occupation as with Zionist Jews in Palestine.

In a way, on a more complex level, the rise of a nation’s sense of loyalty based on geography is a kind of return to pagan attachments to place. For nationalists, attachment to a territory is a foundation-stone. In the United States stories and music celebrating the pilgrims landing, the revolutionary cites like Bunker Hill and the settling of the American West are examples.

Religious Zionism to Nationalist Manifest Destiny

Earlier we said that what separates monotheism from polytheism is the expansionary, missionary zeal of monotheism. This tendency was also characteristic of many nation-building projects throughout history. Both monotheism and nationalism wish to expand. There is an exclusive commitment to either one religion or one nation; yet once that exclusive commitment is made, the religion or nation sometimes advocates for expansion around the world. We can see this with Western imperialism, which in many cases sends in the missionaries first.

Commonalities in the Processes of Socialization into Monotheism and Nationalism

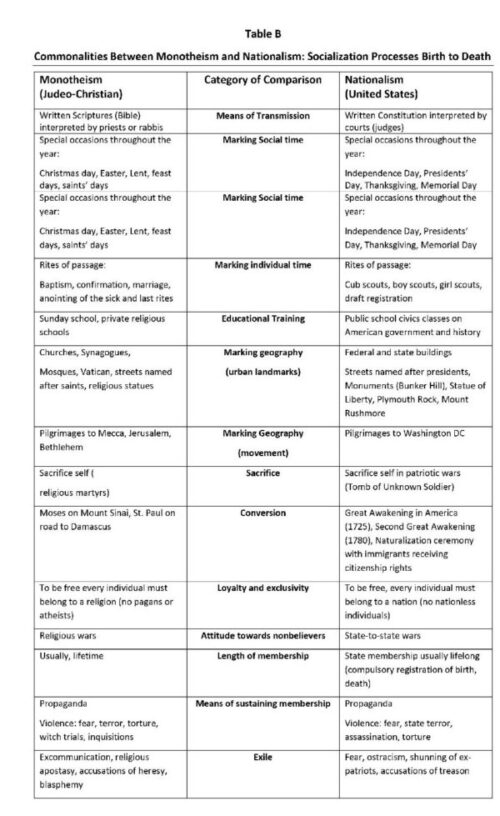

Table A showed the relatively static commonalities between monotheism and nationalism. These center mostly on beliefs and the use of propaganda paraphernalia on people. But there are many commonalities in how people are socialized over time. These include methods of transmission, rites of passage, special occasions throughout the year, educational training and geographical pilgrimages. We also have similarities on conversion experiences, how loyalty and exclusivity are maintained and how religious and nationalistic populations are ex-communicated. Please see Table B for a summary.

Qualification: What About the Place of Islam in Nationalism?

It probably crossed your mind that I did not include Islam in my monotheistic roots of nationalism comparisons. Certainly, Islam is monotheistic. Furthermore, when we look at Islamic fundamentalism, it might seem like there is fanatical nationalism at work.

But a closer look shows that Islam has similar internationalism as the Catholics. Being fanatical about your religion that you will kill and die for it is not necessarily nationalism.

Why did Islam not develop a nationalism the way the Jews and the Christians did?

There are at least the following reasons.

- Western nationalism was inseparable from the development of industrial While Islam had a “merchant capital” phase of capitalism, they never went through the industrialization process that capitalism did in the West. Industrialization is very important in pulverizing intermediate loyalties.

- Nationalism in the West was not built by one country at a time. The Treaty of Westphalia in 1689 created a system of states that became the foundation for nationalism at the end of the 18th. There was no system of states that existed in West Asia at the time. Predominantly what existed were sprawling empires, not nation-states.

- In the 19th and 20th century, Islam has become a religion of the oppressed. European nation-states were not fighting against imperialism when they arose in England, France, the United States, and Holland. Their development was not shackled by fighting defensive wars. West Asian nationalism could not develop autonomously.

My article began by drawing your attention to how powerful nationalism is in swaying people to be loyal to strangers they have never met as well as to kill and die for them just because they occupy the same territory. I drew some boundaries around the meaning of nationalism and pointed out how people confuse nationalism with nations, states and ethnic origin. Then, following the work of Anthony Smith, I identified four sacred dimensions of national identity, five parts of its doctrine and three phases of nationalism.

Next, I discussed the need for nationalists to first tear down competing loyalties of kinship ties, ethnic loyalties, regional and class identifications in order for it to rule without competition. After pulverizing intermediate loyalties, it then builds up a centralized state through postal networks, national newspapers, railroads and telegraph systems which act as networks for nationalism. I raised and answered questions about the relationship between the state and religion. Do religion and the state compete with each other? Do they replace each other? Are they mutually supportive? Then I gave an example of how the radical wing of the French Enlightenment used religious paraphernalia in the hopes of creating a society based on reason, which came out of the French revolution.

My article then takes a step further. I argue that the state uses a particular kind of religion to strengthen its loyalty. It is no accident that the countries of the world that never developed nationalism in the 18th and 19th centuries were not Jews and Christians. There is something about the monotheism of the Jews and Christians that was the best foundation to build nationalism and the centralized state that developed in Europe in the 19th century. Most of the rest of my article shows the similarities in the beliefs and dramatization between monotheism and nationalism. Lastly, I close with a table that shows how similar nationalism and religion are in their socialization processes from birth to death. I also addressed the question of why Islamic monotheism did not lead to Islamic nationalism.

It is no wonder that nationalism has such a hold on people. Since most Europeans and Yankees are either Protestant, Catholic or Jewish, nationalist indoctrination already has an infrastructure built in with monotheistic beliefs, practices, and socialization. Sure, there are some people who are monotheists and not nationalistic. And there are some people who are nationalistic but not very monotheistic. But most people in Europe and Yankeedom are both. Most of those people are the working-class people who buy both nationalism and monotheism and then get killed or maimed in wars, at least partly because they’ve drunk the Kool-Aid.

• First published in Socialist Planning After Capitalism

-

-

- Image credit: Gustave Doré, Moses Breaks the Tables of the Law, 1866, from The Founding Myths: Why Christian Nationalism Is Un-American by Andrew L. Seidel

-