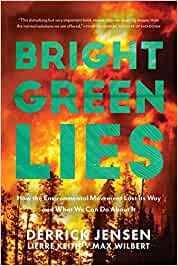

“Knowledge of death helps us also to find a good road,” Jack D. Forbes tells us, “because perhaps it can bring us to deep considerations of our place in nature.” I recall this reflection Forbes makes, among other revelations, in his 1978 book Columbus and Other Cannibals, now, rather queerly, in relation to the environmental movement. Written by Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, and Max Wilbert, Bright Green Lies comes at a critical moment, as this machine called by the name civilization wages its war on nature, to the devastation of the living world.

“Knowledge of death helps us also to find a good road,” Jack D. Forbes tells us, “because perhaps it can bring us to deep considerations of our place in nature.” I recall this reflection Forbes makes, among other revelations, in his 1978 book Columbus and Other Cannibals, now, rather queerly, in relation to the environmental movement. Written by Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, and Max Wilbert, Bright Green Lies comes at a critical moment, as this machine called by the name civilization wages its war on nature, to the devastation of the living world.

Analyzed here, bright green environmentalism occupies the position that industrial civilization, otherwise unsustainable, can be salvaged into sustainability through continued, rapid technological innovation. Anthropocentric in its thinking, thus also egocentric, all for the industrial human, rather than ecocentric, it argues for an “environmentalism,” as such, “less about nature, and more about us.” But, as the authors show us, lies should not be dressed up as truths, no matter how desperately one might desire to avoid discomfort.

Central to the analysis in Bright Green Lies, which criticizes this anthropocentrism, we see a critique of technology, a subject also seen in other forms before in Jensen’s work, such as in his and George Draffan’s 2004 book Welcome to the Machine. Technology should not be seen as truly neutral, indeed as if apolitical, since any such neutrality simply cannot be so in technology’s connection to culture.

Technic, a term from Lewis Mumford, refers to this relation. “A social milieu,” the authors write of it, “creates specific technologies which in turn shape the culture.” On this point, they refer to Mumford’s two-volume work The Myth of the Machine, particularly the first volume Technics and Human Development, published in 1967. On what he terms “authoritarian technics,” as referenced by the authors, Mumford, writes in his 1964 article “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics”:

[A]uthoritarian technics is a much more recent achievement: it begins around the fourth millennium B.C. in a new configuration of technical invention, scientific observation, and centralized political control that gave rise to the peculiar mode of life we may now identify, without eulogy, as civilization. Under the new institution of kingship, activities that had been scattered, diversified, cut to the human measure, were united on a monumental scale into an entirely new kind of theological-technological mass organization.

Mumford’s phrase “theological-technological mass organization” matters. Here, as I do, one might recall, as examples most familiar to many, Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel Brave New World and George Orwell’s 1949 novel 1984. We might well consider, as Margaret Atwood remarks, the dystopian arising from the utopian: “Why is it that when we grab for heaven—socialist or capitalist or even religious—we so often produce hell?” Civilization’s battle against biology itself, being in its hatred for nature, seems to be hell in reality, with heaven as fantasy. One discovers only a deceitful promise to deaden the consciousness and counteract any social change against the machine. Both ecocidal and death-bringing, as it pretends to be ecological and life-giving, this deceit seems to be characteristic of bright green environmentalism.

“Around the world,” the authors write, “frontline activists are fighting not only big corporations but also the climate movement as wild beings and wild places now need protection from green energy projects.” It would be too simplistic, then, to misrepresent this most serious critique as seeing all technology, from the dawn of humankind, as being an inherent act of destruction. Context matters, clearly, with us in this ongoing cultural transition into what Neil Postman calls technopoly. In his 1992 book Technopoly, Postman defines it as a “totalitarian technocracy,” characterized by “submission of all forms of cultural life to the sovereignty of technique and technology.” It embodies the arrogant sense of solutionism in technological innovation, man’s new theology, under current industrial civilization. Making problems, as the authors here show, the industrial human’s use of technology, also including biotechnology, has been destructive, rather than restorative, toward the living world.

“These technologies will not save the earth,” Keith writes in the prologue, adding: “They will only hasten its demise.” And so, as the authors show, it simply does not make sense for us, as Jeff Gibbs posits this question in his 2019 film Planet of the Humans, to believe that machines built by industrial civilization can save us, including the living world being colonized at the biological level, from industrial civilization. “Weapons are tools that civilizations will make,” the authors write, “because civilization itself is a war.”

As it has come to be, industrial civilization poses many problems for the living world, among those noted by the authors, which cannot be worked around by only more technology. Seen as if its own theology, our technology seems to keep us within a paradigm, one that has been anthropocentric, consuming nature around civilization to feed its apparently bottomless greed. On civilization, the authors continue:

Its most basic material activity is a war against the living world, and as life is destroyed, the war must spread. The spread is not just geographic, though that is both inevitable and catastrophic, turning biotic communities into gutted colonies and sovereign people into slaves. Civilization penetrates the culture as well, because the weapons are not just a technology—no tool ever is. Technologies contain the transmutational force of a technic, creating a seamless suite of social institutions and corresponding ideologies. Those ideologies will either be authoritarian or democratic, hierarchical or egalitarian. Technics are never neutral.

Here, after this passage, the authors reference Chellis Glendinning, author of the 1990 book When Technology Wounds, who writes: “All technologies are political.” Power remains primary in how we must orient ourselves, in terms of our understanding, regarding the element of the theological-technological. “The mechanistic mind is built on an epistemology of domination. It wants a hierarchy,” the authors write. “It needs to separate the animate from the inanimate and then rank them in order of moral standing.” Man comes to be driven in making an order of things under which he can name all and make the world’s meaning with relation to himself, seeing woman and nature as subject to his desire. Imagined as freedom, seen for man as the self-made individual in the man-made world, it becomes realized as slavery.

On the mechanical mind, Sir Francis Bacon, inquisitor at witch trials and inventor of the scientific method, describes his objective, science as he saw it, as “dominion over creation.” And René Descartes adds: “I have described this earth, and indeed this whole visible world, as a machine.” Clearly, even if seen among bright green environmentalists analyzed by the authors, one can see the tradition of Bacon and Descartes continuing today across social movements. The mechanical mind appears most evident in man’s continued desire to carve out nature and claim the corpse as his, colonizing and occupying that which he feels driven to possess.

Narcissistic, consuming everything around it, the mechanistic mind, as the system of beliefs with this desire, insists upon itself as the center of all things. Any identity developed from this ideology becomes one based on destruction, thus doomed to be a repetition of reversals “in a reversal society,” as Mary Daly remarks. The death of the flesh—indeed, what Luce Irigaray describes as “the murder of the mother”—becomes life for the self, with destruction as creation, emptiness as fulfillment. It can be characterized by what Erich Fromm analyzes as necrophilia, being “the passion to transform that which is alive into something unalive,” “the exclusive interest in all that is purely mechanical.”

“Having declared the cosmos lifeless,” the authors write, “industrial humans are now transforming the biosphere into the technosphere, a dead world of our own artifacts that life as a whole may not survive.” Technological fundamentalism, a term used by David W. Orr in his 1994 analysis, discussed by Robert Jensen in his 2017 book The End of Patriarchy, has been deployed for describing this ideology against biology and ecology. Technology, although substituted for the sacred, is killing the living world, civilization being its consumer.

Seen in the example of bright green environmentalism, the authors critique this dependency, which, in the increasing enslavement to the machine, seems a tell-tale sign of desperation, not hope. “Unable to separate can do from should do,” Orr writes, “we suffer a kind of technological immune deficiency syndrome that renders us vulnerable to whatever can be done and too weak to question what it is that we should do” (336). At its most basic, there seems to be a failure to see boundaries, as one becomes only more obsessed with breaking them, including everything in nature to be dominated.

A declared sense of “dominion over creation,” as Bacon would have it, does not seem compatible with local knowledge and natural variation, as globalization, and the declared universality of dominant western knowledge, has worked to make the world a monolith. On biodiversity, Rachel Carson, whom the authors cite, writes in her 1962 book Silent Spring: “Nature has introduced great variety into the landscape, but man has displayed a passion for simplifying it.” Just as Carson identifies man’s desire to control nature, to its simplification on his terms, Vandana Shiva likewise identifies it, much as the authors do here, in the violence of the Green Revolution, analyzed in her 1993 book Monocultures of the Mind. “The destruction of diversity and the creation of uniformity,” Shiva writes, “simultaneously involves the destruction of stability and the creation of vulnerability.” Nature becomes more bound to what Barbara Christian, in her 1987 essay “The Race for Theory,” terms monolithism, becoming more so mystified, thus brought into destruction, in man’s claim to control all life. “Ideologies of dominance,” as Christian analyzes them, appear to manifest in man’s technology, to manipulate nature, rather than letting the living world simply be in its multiplicity.

Among the consequences of man’s attempted total control of nature, the world has witnessed a radical decrease in biodiversity, corresponding with the rise of industrial civilization as it colonizes nature—indeed, life—itself. As the authors note, Carson felt an urgent sense, first and foremost, of us needing to save, in her words, “the living world” in its beauty, a being in and of itself, unenslaved by any man-made sense of meaning. Added to this sensibility of hers, Carson felt, also in her words, “anger at the senseless, brutish things that were being done,” a feeling seen in Shiva’s work. And, with their own work, Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert seem to follow Carson’s and Shiva’s sensibilities, being kindred witnesses for nature, seen in this time of great need.

“Mainstream environmentalists,” the authors write, “now overwhelmingly prioritize saving industrial civilization over saving life on the planet.” As but one example of civilization as contagion, in his article “The Race to Save Civilization,” Lester Brown argues how we can “save civilization,” because the living world is, so he says, “going to be around for a while.” Indeed, as Wilbert writes in his review of Brown’s 2009 book Plan B 4.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization, it is “fundamentally anthropocentric,” neglecting a critique of both capitalism and civilization. “If we can get the market to tell the truth,” Brown writes, “then we can avoid being blindsided by a faulty accounting system that leads to bankruptcy.” But it does not seem wise to put our hope in the market, when, as it has been so, the market would seem unlikely to tell any truth not manipulated by the green power of profit.

Recalling the work of Robert Jay Lifton, the authors remind us that, before “any mass atrocity,” one “must have a claim to virtue.” Aside from here in Bright Green Lies, Jensen writes of this “claim to virtue” in his 2000 book A Language Older Than Words. Jensen references Lifton’s 1986 book The Nazi Doctors in which, among the doctors at Auschwitz, we see what it means to claim virtue and collaborate in atrocity. A few among us might well come to consciousness of the falsities, seeing it all for what it actually is. “But the rest of us want this bright, happy future, and we refuse to close the distance,” the authors write. “We don’t want to know about the acid rain falling, the fish strangling, and the rubble that once was mountains going up in smoke.” There seems to be a true fear of the real world there. Rather than face reality, as we should do, without lying to ourselves, we retreat into fantasy worlds, where we can have it all—even when it will not work. Desperate, one comes to convince oneself that the atrocity, whatever it might be, “is not in fact an atrocity, but instead a good thing.” Disembodied and dismembered, we become the despisers of the earth.

Against the sacred, civilization has been presented as the cure, when it worsens the living world, akin to mere snake oil as healing salve, in a false hope for some miraculous salvation. Such would seem to be the man-eat-world world logic of environmentalism against the environment. In their analysis, the authors show a selection of lies in terms of technology, ones which not only will not work but also make things much worse. Certainly, a very commodifying vocabulary, a quality of the mechanical mind considered here, might well sell the environment to buyers, maybe even those considerably invested in its consumption, but that does not seem compatible with saving the living world. As we see argued in Bright Green Lies, the color green for the modern environmental movement has ended up becoming far less about the living world than about the money to be made from nature by man’s exploitation of it. Really mistaken for its own religion, money, in a symbiosis with technology, should not be that on which we form our faith.

“By acquiescing in an act that can cause such suffering to a living creature,” Carson asks us in Silent Spring, “who among us is not diminished as a human being?” Human beings have been diminished by seeing all of nature, including our bodies and ourselves, as though mechanical, both deadened and dispossessed. But, as seen before, in our fear and guilt, being against nature, we lie. Such has been seen in man’s dominion over woman. Man tells himself all manner of lies, even seeing woman hating as a way of life, occupying himself with it as if his innermost self, all in his attempt to alleviate his own fear and guilt over the subjection of women.

“Civilization consumes the circle, so all civilizations end in collapse,” Keith writes, asking: “How could it be otherwise if your way of life relies on destroying the place you live?” Civilization, in its doing of domination, as can be apprehended in its current form, must die for nature—indeed, all life and the interactions therein—to live in the living world. Identity should not be insisted upon as collapsing all others around the self into it, for it leads to an idea of the individual as a destroyer, caught in his own illusion of being a creator. Of the work to be done on humanity’s part, that beyond the life of Bright Green Lies, Jensen writes in the afterword:

This way of living will not and cannot last. What we do now determines how much of the planet remains later. We can voluntarily reduce the harm caused by this culture now, and work to create spaces where nature can regenerate, or we can continue to allow—indeed, to subsidize—further destruction of the planet’s ecological infrastructure. And while that may allow the economy to limp along a few more years, I guarantee that none of us—salmon, right whales, piscine life in the oceans, humans—are going to like where that takes us.

Human beings must consider our place in nature, not as its masters, becoming those who control it, as if the creators of all, but rather, in our being, as another part of the living world. Humanity must reject civilization’s dominion over nature. To resist the machine, one must really come to terms with biology, rejecting that mechanical mind that makes us go against nature into nothingness. There must be an understanding of the connectedness of beings in the living world, that we do not exist as disembodied and dismembered parts in any machine. “All things participate in the circle of death,” Forbes reminds us, “but as mentioned earlier, death is life.”