He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy;

But he who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity’s sun rise.– William Blake, Eternity

Great songwriters, like great poets, are possessed by a passionate melancholic sensibility that gives them joy in the telling. They seem always to be homesick for a home they can’t define or find. At the heart of their songs is a presence of an absence that is unnameable. That is what draws listeners in.

Great songwriters, like great poets, are possessed by a passionate melancholic sensibility that gives them joy in the telling. They seem always to be homesick for a home they can’t define or find. At the heart of their songs is a presence of an absence that is unnameable. That is what draws listeners in.

While great songs usually take but a few minutes to travel from the singer’s mouth to the listener’s ears, they keep echoing for a long time, as if they had taken both singer and listener on a circular journey out and back, and then, in true Odyssean fashion, replay the cyclic song of the shared poetic mystery that is life and death, love and loss, the going up and coming down, the abiding nostalgia for a future home.

Kris Kristofferson’s songs keep echoing in my mind.

My very old mother, as she neared death, would often tell me, “Don’t let me go.” I would tell her I was trying, knowing my efforts were a temporary stay and that through our conversations we were building what D. H. Lawrence called her “ship of death.”

Build then the ship of death, for you must take

the longest journey, to oblivion.

And die the death, the long and painful death

that lies between the old self and the new.***

We are dying, we are dying, so all we can do

is now to be willing to die, and to build the ship

of death to carry the soul on the longest journey.***

And the little ship wings home, faltering and lapsing

on the pink flood,

and the frail soul steps out, into her house again

filling the heart with peace.

In those days she also used to ask me: “Now that you have lived more of your life in Massachusetts than in New York City, where do you say you are from and which do you consider your home?” I didn’t know what to say but would wonder where I would like to be buried, as if it mattered. I would be dead. Home. I don’t think so. Not underground, so why does it matter where. Home isn’t a place for permanently sleeping. It’s the place from which we launch our ships out into the world. The place that we discover when all our sailings are done.

Where was the lightning before it flashed?

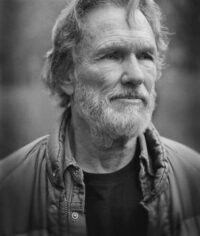

Kris Kristofferson, who is now an old man in his mid-80s, is an astonishing songwriter, a man of faith and conscience, and a humorously devilish performer with an on-stage persona of a spiritual satyr. He has written and performed some of the finest songs in the American songbook. A man’s and a woman’s man, he has written songs of exquisite passion and sensitivity and rough rollicking freedom that only an emotionless zombie would fail to be moved by. And in the last 10 or so years he has fearlessly confronted his mortality, writing many brave songs that bookend his earliest hits, such as Help Me Make It Through the Night.

I have loved and listened to his music for a long time and have wished to honor him for years.

This is my small tribute to a great artist.

Counterpose what is perhaps his most well-known song, Me and Bobby McGee, first made famous by the rocking swirling twirling wild dervish Janice Joplin, a former lover so I’ve heard, with his lilting poem that is little known: Shadows of Her Mind. Two meditations in very different song styles on love, loneliness, searching, loss, and the secrets of one’s soul – a magician at work. Whether partly truth or partly fiction doesn’t matter. Secrets are secrets.

Kristofferson broke barriers when he found success in Nashville’s country and western scene in the early 1970s. He made explicit the sexuality and the yearning for love that underlay traditional country music. The endless yearning that never ends. Its secret. Not just sex in the back room of a honky-tonk, but the “Achin’ with the feelin’ of the freedom of an eagle when she flies,” as he sings in Loving Her Was Easier. Something intangible. True passion for love and life.

He was an oddball. Here was a man whose inspiration for Me and Bobby McGee was a foreign film, La Strada (The Road), made by the extraordinary Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini. Not the stuff of movie theaters in small Texas towns. In the film, Anthony Quinn is driving around on a motorcycle with a feeble-minded girl whose playing of a trombone gets on his nerves, so while she is sleeping, he abandons her by the side of the road. He later hears a woman singing the melody the girl was always playing and learns the girl has died. Kris explains:

To me, that was the feeling at the end of ‘Bobby McGee.’ The two-edged sword that freedom is. He was free when he left the girl, but it destroyed him. That’s where the line ‘Freedom’s just another name for nothing left to lose’ came from.

Not exactly country, yet a traditional storyteller, a Rhodes scholar and a former Army Captain, an Oxford “egghead” in love with romantic poetry, a sensitive athlete, a risk-taker who gave up a teaching position at West Point for a janitor’s job in Nashville to try his hand at songwriting, a patriot with a dissenter’s heart, he is an unusual man, to put it mildly. A gambler. A man who knows that heaven and hell are born together and that the body and soul cannot be divorced, that all art is incarnational and meant to be about ecstasy and misery, not the middle normal ground where people measure out their lives in coffee spoons. He’s always wanted to tell what he knew, come what may, as he sings in To Beat the Devil:

I was born a lonely singer, and I’m bound to die the same,

But I’ve got to feed the hunger in my soul.

And if I never have a nickel, I won’t ever die ashamed.

‘Cos I don’t believe that no-one wants to know.

What do people want to know? A bit here and there, I guess, but not too much, not the secrets of our souls. Not the truth about their government’s killers, the lies that drive a Billy Dee to drugs and death and the hypocritical fears of cops and people who wish to squelch the truths of the desperate ones for fear that they might reveal secrets best buried with the bodies. Secrets not about the dead but the living.

There are only a handful of songwriters with the artistic gift of soul sympathy to write verses like the following, and Kris has done it again and again over fifty years:

Billy Dee was seventeen when he turned twenty-one

Fooling with some foolish things he could’ve left alone

But he had to try to satisfy a thirst he couldn’t name

Driven toward the darkness by the devils in his veinsAll around the honky-tonks, searching for a sign

Gettin’ by on gettin’ high on women, words and wine

Some folks called him crazy, Lord, and others called him free

But we just called us lucky for the love of Billy Dee

Like William Blake, one of Kristofferson’s mentors – “Can I see another’s woe/And not be in sorrow too?/Can I see another’s grief/And not seek for kind relief?” – Billy Dee captures in rollicking sound more truth about addiction than a thousand self-important editorials about drugs.

Kristofferson joins with Dylan Thomas, the Welsh bard, another wild man with an exquisite sense for the music of language and the married themes of youth and age, sex and death, love and loss, home and the search, always the search:

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose

My youth is bent by the same wintry fever.

Although most of his songs lack overt political content, such concerns are scattered throughout his massive oeuvre (nearly 400 songs) where his passion for the victims of America’s war machine and his respect for great spiritual heroes like Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and John and Robert Kennedy ring out in very powerful songs that are not well known. Note his use of the word they in They Killed Him, surely not a mistake for such a careful songwriter.

And in The Circle, a song about Bill Clinton killing with a missile an Iraqi artist and her husband and the wounding of her children, his condemnation is powerful as he links it to the disappeared of Argentina in a circle of sorrow. Of course, no one is responsible.

“Not I” said the soldier

“I just follow orders and it was my duty to do my job well”

“Not I” said the leader who ordered the slaughter

“Im saddened it happened, but then, war is hell”

“Not us” said the others who heard of the horror

Turned a cold shoulder on all that was done

In all the confusion a single conclusion

The circle of sorrow has only begun

As everyone knows, songs have a powerful hold on our memories, and sometimes we learn ironic truths about them only years later.

When I was young, my large family, consisting of my parents and seven sisters and me – Bronx kids – would go on vacation for a week in the late summer to a farm called Edgewater. We would pack our clothes in cartons weeks in advance and would load into the car like sardines layered in a can. On the trip north to the Catskill mountains, in our wild excitement we would sing all sorts of happy songs, many from Broadway shows. As we approached the farm, we would go crazy with excitement and sing over and over the repetitive song we had learned somewhere: We’re Here Because We’re Here Because We’re Here. To us it was a song of joy; we had arrived at our Shangri-La, our ideal home, paradise regained. To this day, the name Edgewater is like Proust’s madeleine dipped in tea for many of us.

What we didn’t know was that the song we were singing was the sardonic song that WW I soldiers sang as they awaited absurd and senseless death in the mud and rat-filled trenches of the war to end all wars. Sardonic words to them and joy to us. They were there because they were there and it was meaningless. We sang it out of joy. So Blakean:

Man was made for joy and woe

Then when this we rightly know

Through the world we safely go.

Joy and woe are woven fine

A clothing for the soul to bind.

To listen to Kris Kristofferson’s vast oeuvre is a confirmation of that Blakean truth. It is to realize that all those songs he has written and sung have been his way of fulfilling the words of another Romantic poet who was Blake’s contemporary, John Keats. Keats called life “a vale of soul-making,” meaning that people are not souls until they make themselves by developing an individual identity by doing what they were meant to do.

In Ken Burns’ fascinating documentary series, Country Music, Kris answers the question of why he took such a radical turn early on and gave up his military road to success for a lowly job as a janitor in Nashville where he hoped to write songs. He said:

I love William Blake…. William Blake said, “If he who is organized by the divine for spiritual communion, refuse and bury his talent in the earth, even though he should want natural bread, shame and confusion of face will pursue him throughout life to eternity.

When he answered this call of the spirit and took such a dramatic turn away from the conventional road to success, his mother wrote him a letter essentially disowning him (“dis-owning” – an interesting word!). When Kris showed it to Johnny Cash, Cash said, “Isn’t it nice to get a letter from home?”

Not devoid of humor, Kristofferson wrote Jessie Younger, a catchy tune that no doubt concealed his pain while sharing it, an example of his extraordinary ability to use words in paradoxical ways. A close examination of so many of his lyrics leaves me aghast at his talent.

There are just a handful of songwriter/performers who can match the art of Kris Kristofferson. Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen come to mind, men whose work also contains that deep spiritual questing for home. Both have been greatly celebrated in recent years, Dylan with the Nobel Prize and Cohen with accolades after his death.

Kris Kristofferson may have been “out of sight and out of mind” in recent days, so I would like to bring him back to your attention and salute him.

Thank you, Kris. You are an inspiration. Blessings.

Encore: The Last Thing to Go