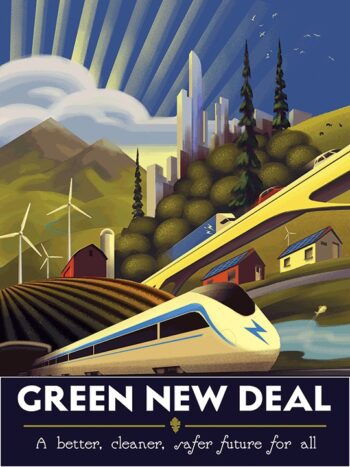

The most popular poster for the Green New Deal reveals startling assumptions.

Looking at it as a whole, ignoring the details for now, the poster exhibits a sense of movement. The train is the focal point and duplicates similar depiction of trains, for example, in vintage French posters. These huge machines, emblematic of the Modern Age, are a graphic cliché. Similar renditions are found in posters all over Europe and the United States.

The vehicle bridge reinforces the sense of speed and upward thrust. The city-scape, with its high-rises elevated in the distance, recalls the notion of “A City upon a Hill,” a phrase from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount that came to refer to America’s global role as a refuge and a source of hope in an otherwise hopeless world. A questionable proposition these days.

The vehicle bridge reinforces the sense of speed and upward thrust. The city-scape, with its high-rises elevated in the distance, recalls the notion of “A City upon a Hill,” a phrase from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount that came to refer to America’s global role as a refuge and a source of hope in an otherwise hopeless world. A questionable proposition these days.

There are predictable elements in the poster like the wind turbines and the birds, who, thankfully, have managed to survive the rotating blades. And the lone fish suspended in air influenced, we imagine, by the graphic thrust to contribute in its modest way to the overall upward movement. The stylized trees are odd in a poster meant to emphasize environmental issues. Another disturbing element is the rolling agricultural field extending to the horizon that recalls corporate agriculture. Maybe the traditional barn is meant to mitigate the impression that these fields are indeed politically incorrect. However, the most incomprehensible portion of the poster is the highway flyover, replete with cars and a truck. Are we to believe that these are electric vehicles? And where are they rushing to?

Taken as a whole the poster shouts Progress. This is most obvious when we assume that while the train may be symbolic of public transportation, most often when selling the GND advocates despair that the US still has no bullet trains. Is this the intention of the Green New Deal – bullet trains as Green Progress? A future world, in other words, not unlike the one we suffer from now, but faster. And sustainable, whatever that means. Which is the problem. It means nothing.

Taken as a whole the poster shouts Progress. This is most obvious when we assume that while the train may be symbolic of public transportation, most often when selling the GND advocates despair that the US still has no bullet trains. Is this the intention of the Green New Deal – bullet trains as Green Progress? A future world, in other words, not unlike the one we suffer from now, but faster. And sustainable, whatever that means. Which is the problem. It means nothing.

The trajectory of Green Progress hurtles us along a track where resources will be consumed to maintain a style of life, albeit “green,” that we instead need to abandon. Why, for example, do we need bullet trains? Why not direct a fraction of the money needed to build bullet trains and refurbish track and rolling stock of the already-in-place Amtrak lines? And instead of speed the goal, have an affordable, pleasurable experience be the purpose for train travel.

Unfortunately, slow options for travel run against the century-long indoctrination that progress is defined by speed. Speed is an addiction, or at least a state of mind, that no one expected to be questioned until the worldwide impositions of the COVID-19 lockdowns. Politicians in a panic wrenched the gears of Capital to a full stop. Interestingly enough, after the public’s initial shock of the restrictions receded, the press reported that, despite the added stress of families trying to balance work at home, children’s education, and safe health practices, people actually enjoyed the decompression from their previous frantic life-styles.

Imagine the circumstances where, on the contrary, we leisurely experience a slower pace, not one forced upon us. The simple fact is that integral to a pleasurable life is slowing down our lives. Besides it is widely recognized to be good for the environment—less commuting and fewer planes brought us good air. Well, good air when the wind is blowing the smoke from wildfires elsewhere.

Progress connotes speed, but also shopping—bigger and faster cars, but also larger homes, TV screens, and waist-lines. The GND is essentially an industrial policy to support corporate profits through public/private schemes. Ostensibly this policy creates jobs and is tied to a Jobs Guarantee as a foundational element of the new Liberal Green Order (LGO).

No one doubts that all variety of work needs to be done to repair the deterioration of the environment due to manufacturing, extractive industries, and industrial agriculture. But do we need the federal government to massively hire a new bureaucracy to gear up for “green” jobs, which in turn will spawn bureaucracies in every state, region, and city to filter the largess from D.C.?

To bypass this so-called “strong state,” a grant directly to every resident sufficient to lead a comfortable life, but not one of excess, opens the possibility of people abandoning their bullshit jobs to do socially necessary work. No other proposal most clearly addresses the issue of racial and economic justice. With the guarantee of an income to meet essential needs (and with universal healthcare established, besides a few other social benefits enjoyed by the citizens of other countries), the restraints of wage-slavery are removed to make available a variety of social activity. For instance, the possibility of genuine solidarity was manifest in France last Spring, when COVID-19 restrictions prohibited entry of seasonal agricultural workers, forcing the government to establish a website for volunteers to sign up to help the farmers with the harvest. More than 200.000 signed up immediately.

Of course, not all environmental restoration need be done by volunteers for little or no pay. Subsidies distributed by local authorities should be available for long term commitments.

The point here is to respond to several catastrophes that are hitting us simultaneously by galvanizing the citizenry to take responsibility for addressing them. This sounds like a formidable task, if not foolhardy and unachievable. The advocates of the GND refer to two programs from the FDR era that were directed from Washington — the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, as successful examples of popular mobilizations.

The difference between that era and ours is that many more citizens, beyond the unemployed, need to be enrolled in socially necessary projects. The GND highlights a few, for instance, installing solar panels, developing cabled internet access to rural areas, constructing infrastructure for electric transit, and forest restoration. We don’t hear, though, that our food system is on the verge of collapse and to maintain a healthy (the operative word) supply of nutrition industrial agriculture must be abolished for ruining the soil and producing garbage to eat. If local small scale farms and ranches are to be developed, it will take millions of people across the country to implement the task. Chris Smaje, a British sociologist-turned-farmer, delves into the subject in his new book A Small Farm Future.

The difference between that era and ours is that many more citizens, beyond the unemployed, need to be enrolled in socially necessary projects. The GND highlights a few, for instance, installing solar panels, developing cabled internet access to rural areas, constructing infrastructure for electric transit, and forest restoration. We don’t hear, though, that our food system is on the verge of collapse and to maintain a healthy (the operative word) supply of nutrition industrial agriculture must be abolished for ruining the soil and producing garbage to eat. If local small scale farms and ranches are to be developed, it will take millions of people across the country to implement the task. Chris Smaje, a British sociologist-turned-farmer, delves into the subject in his new book A Small Farm Future.

Partisans of the GND, when they are not harking back to FDR’s work programs, often compare the calamity ahead of us to the massive military buildup for WWII, but this is a fallacious analogy. Then relatively direct commands – build tanks, ships, guns – were assigned to corporate bosses who knew what to do. Our situation today doesn’t resemble a war-time economy. This is not to discount the patriotism of millions to civilians who entered the factories and shipyards (including many women who promptly lost their industrial status when the troops returned).

What we face is a country-wide diversity of tasks that no Captains of Industry (if any can be found) are equipped to undertake. And instead of patriotism driving the population to participate, an ecological internationalism seems more appropriate as current motivation. An internationalism, however, that’s grounded on democratic participation at the local level — all over world. The solidarity necessary to transform a profit-driven economy arises from local actions, for instance, to choose one example, the rise of Mutual Aid groups across the world to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 lockdowns. People participate in these activities because they are invested in fostering a good life for themselves and their neighbors. There’s no place for Progress here. Or, rather, we need to define progress as the avoidance of imminent catastrophes in pursuit of a life of abundant joy.