Cultural containment meant “ring around the pinkos”

— The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, Frances Stonor SaundersLeftist Patron Saints

What do the following people have in common: Noam Chomsky, Cornel West, Naomi Klein, Robert Reich, Michael Albert, Howard Zinn, Amy Goodman, Medea Benjamin, Norman Solomon, Chris Hedges, Michael Moore, Greg Palast, and Chip Berlet? With the exception of Norman Solomon and Chip Berlet, these are household names among “progressives”. What they appear to have in common is that they are “left.” How far left? On the surface, they appear to run the full spectrum. After all, Chomsky and Michael Albert are anarchists. Most, if not all, of the rest are advocating some kind of social democracy. Robert Reich and possibly Amy Goodman are New Deal liberals. Have we missed any tendency? Is that it? Yes, we are missing a tendency. The Leninist tradition, whether Trotskyist, Stalinist or Maoist. Are there reasons they are not included?

Why would the most supposedly leftist of all tendencies, the anarchists, get airtime on a show like Democracy Now, while Leninists such as Michael Parenti or Gloria La Riva are rarely, if ever, invited? A crucial key to understanding why this is the case is to clarify the differences between the Old and the New Left.

The Old vs the New Left

What all these patron saints have in common is that they are members of the New Left in the U.S. as opposed to the Old Left. The New left grew up in the early 1960’s on the basis of rejecting the Soviet Union as a model for socialism. For the New Left, some form of social democracy or participatory democracy (anarchist) was the best model. Additionally, the old left emphasized that social class — specifically the working class — was the agent of revolutionary change. The New Left rejected this. For them, the working class has been bought off by capitalism and was no longer a revolutionary class. The New Left turned to philosophers like Herbert Marcuse who claimed that students were the revolutionary class worth organizing.

At the same time, some sections of the middle-class civil rights movement organized around Martin Luther King (a social democrat). The women’s movement had two wings, the liberal Betty Friedan wing and the radical lesbians. But what both these New Left systems of stratification had in common was that race and gender were more important than social class.

There were exceptions to the rule. For example, while the Weatherman were anti-working class, they were secretive (Leninist), and identified with anti-imperialism and the necessity of armed force in order to fight. They tended to idolize third world countries and blindly accept their leadership. Malcolm X had clear roots in the Black working class and poor and maintained a class perspective. He was murdered before he settled within a leftist tendency, but he seemed to be on the way to Trotskyism when he died. So, in the New Left, there were some Leninist tendencies but mostly the social democratic and anarchist orientations won out.

A fourth major difference between the Old and the New Left was the economy. For the Old Left of the Communist Party of Russia, China and Cuba, capitalism by its very nature has contradictions that will drive it to destruction. All Leninists agreed that capitalism was doomed. For the New Left, capitalism seems to have survived its crisis of the Great Depression and the World Wars and was expanding production. It was thought that capitalism could go on forever. The New Left became increasingly cynical that capitalism could be stopped due to any inherent contradictions. Only by revolutionary will would it be possible for capitalism to be overthrown.

Who developed revolutionary theory? For the Old Left, revolutionary theory was developed by professional revolutionaries inside the Communist Party or by members of trade unions. At least hypothetically, if not actually, Leninist theory should be informed by political practice in organizing the working class and its struggles. On the other hand, led by the Frankfurt school, New Leftist theory was developed not within a party or a union but within the academy. Most New Leftist theory after 1970 came out of universities, whether structuralism, Foucault, post-structuralist or postmodernist. These theories were not informed by any connection to practice. They built on each other and increasingly lost touch with any kind of practical tests. One exception to this academic trend was Murray Bookchin and his anarchist followers.

Next, the Old Left did not think much of democracy. Leninist democratic centralism had limited democracy, but once a party decision was made there was no more arguing. Every member of the party carried out the program. For the New Left, democracy was very important. For the social democratic wing, democracy could be obtained by participating in elections either as an independent party, such as the Socialist party, or even by entering the Democratic Party, as had been done for 50 years by the Democratic Socialists of America. The anarchists would have nothing to do with representative democracy but wanted participatory democracy as in the early years of SDS. This participatory democracy continued in the strikes in France in May 1968, and in the theories of the Situationist International. The social anarchists who followed Murray Bookchin and the Occupy movement of nine years ago incorporated this participatory model.

The attitude towards the arts between the New Left and the Old Left were at opposite ends of the spectrum. The Leninist left thought the responsibility of the artist was to represent reality as it really was from a working-class viewpoint (socialist realism). For the New Left, art was a rejection of the life of the working class. Beat poetry and abstract expressionism moved away from reality and expressed the psychological idiosyncrasies of the artist. What was revolutionary was individual expression.

As for appearance, Leninists tried to emulate the dress of the working-class so that short hair and jeans were a sign of solidarity. For the New Left appearances were determined by the countercultural tastes which included beads, long skirts, bell bottoms and tie-dyed clothes. Among the Leninist Black New Left, dressing in the clothes of the African country they were originally from was an option.

In terms of social evolution, the Old Left embraced Marx’s linear model of primitive communism through three forms of class society before reaching communism. Like the bourgeoisie of their country, they championed the notion of progress through science and technology. The New Left was having none of this. They questioned whether capitalist society was more evolved than what went before and they were skeptical of science in delivering us to the promised land. They were much closer to romantics, who identified with tribal societies, whether in the United States or around the world.

For the Old Left, one’s personal life had little to do with the political world. It was possible to be withdrawn, apathetic or abusive in personal life and that had nothing to do with the revolution. For the New Left, specifically the women’s movement, “the personal was political”. What this meant was that your personal life needed to be a microcosm of the world you wanted to build. That meant you could not have a bad marriage and a good revolution. You had to “be the change you wanted to have happen”. This was enhanced by pot and LSD trips.

Where does psychology fit into the picture? For the Old Left, personal psychological problems were just “nerves” not worth taking seriously. It is understandable that the Old Left was skeptical or cynical of psychology and dismissed it as “bourgeois”. The work of Vygotsky, Luria and Leontiev in Russia remained untranslated, so they had no “communist psychology” to draw from. The New Left was much more interested in psychology. It was very sympathetic to the Freudian left of Wilhelm Reich and Erich Fromm. For the socialist women’s movement Karen Horney was a heroine. Reich’s work The Mass Psychology of Fascism helped explain not only the rise of fascism but the failure of the working class to rise up. For the Black Leninist left, Frantz Fanon was the best at explaining self-hatred among colonial people.

For the Old Left ecology was not an issue. They treated the ecological setting as a backdrop for social evolution which was understood as a higher form of nature. In terms of scale, the Old Left took for granted the nation-state as the smallest, most realistic political body to organize around. The Old Left thought of nature as infinitely fecund and able to carry a growing population without limits. But for the New Left, the ecology movement in the 60’s saw nature as under attack and should be defended and appreciated. The romantic tendency of the New Left meant “going back to nature”. This was later accompanied by the “small is beautiful” movement which fit well with anarchist decentralization concepts. Furthermore, in 1972 the Club of Rome issued its first report stating that the carrying capacity of the planet was limited. This meant that unlimited growth could no longer be sustainable. People had to learn to do with less. For the first time since the eugenics movement, the question of too many people on the planet was broached, however tentatively.

The last categorical difference has to do with the differences in religion and spirituality. For the Old Left, atheism was the ideal and organized religion and spirituality were all part of the same superstition. The New Left was more open to institutionalized religion (as in following Martin Luther King), while making a distinction between institutionalized religion and spirituality (which was separate from organized religion). By the early 1970’s, the New Left became susceptible to Eastern mysticism (TM, yoga) and the Gurus who came with it. Women especially were leaving institutionalized religion for wicca and other neo-pagan traditions. Some New Leftists later morphed into Rudolf Steiner Waldorf education and Gurdjieff movement. Anarchists were more likely to gravitate to the magical work of Aleister Crowley. See table 1 for a summary.

But why does this matter? If the Old Left is marginalized and excluded in the press, magazines and on radio waves today and the New Left — social democrats and anarchists — are welcomed, what does this have to do with Left Gatekeeping? After all, maybe the Old Left is not paid attention to because they are “out if date” with their Leninist vanguard party and mindless defense of the Soviet Union. To some extent this may be so, but that is far from the whole picture.

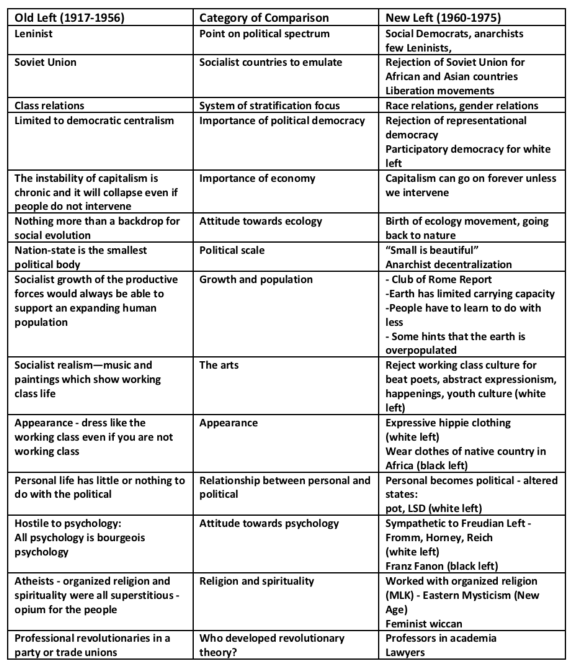

Old Left vs New Left – Table I

The Congress for Cultural Freedom

How it started

In his book The Mighty Wurlitzer Hugh Wilford describes the events that led to the founding of the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF):

In March 1949, the Waldorf-Astoria hotel hosted a gathering of Soviet and American intellectuals, the Scientific and Cultural Conference for World Peace. This was sponsored by the American Popular Front attended by, among others, Paul Robeson and Lillian Hellman. It was a publicity disaster. The State Department derailed preparations by refusing to grant visas to would-be European participants. Anti-communist vigilantes were alerted by the Hearst Press. Disruptions were staged by anti-Stalinists, organized by Sidney Hook. (Page 70)

What it did

In her book The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, Frances Stonor Saunders traces the activity of an organization called the Congress for Cultural Freedom which existed from 1950 to 1967. The secret mission of the organization was to promote cultural propaganda in Western Europe to keep it from going communist. The idea was to make it seem that the cultural criticism of communism coming from the West about the Soviet Union was a spontaneous irruption, rather than stage-managed. The CIA poured tens of millions of dollars into this project.

As it turns out, groups of ex-communists for the most part inadvertently, helped to invent the weapons with which the CIA fought communism. Later, these ex-communists were sidelined as the spies attempted to professionalize their front operations with their Ivy League recruits.

As Stonor Sanders tells it, the congress:

…stockpiled a vast arsenal of cultural weapons — journals, books, conferences, seminars, art exhibitions, concerts and awards. Whether they knew it or not, there were few writers, poets, artists and historians, scientists or critics in post-war Europe whose names were not in some way linked to the covert enterprise. It consisted of former radicals and leftist intellectuals whose faith in Marxism had been shattered by Stalinism. (Page 2)

In terms of propagandistic goals, as Stoner Saunders says, “The most effective kind of propaganda is where the subjects move in the direction you desire for reasons which he believes are his own” (Page 4)

The strategy of promoting the non-communists was to become the theoretical foundation of the agency’s political operations against Communism over the next two decades. (Page 63)

Suitable texts were easily available from the CCF such as Andre Gide’s account of his disillusionment in Russia, Koestler’s Darkness at Noon and Yogi and the Commissar, and Ignazio Silone’s Bread and Wine. Further, the CIA subsidized The New Class by Milovan Djilas about the class system in the USSR. Books with titles like Life and Death in the USSR by a Marxist writer criticizing Stalinism was a book widely translated and distributed with CIA assistance. The compilation of articles made into the book The God That Failed was distributed all over Europe.

On the surface it may seem that the purpose of the CIA front groups was to destroy communism. However, Stoner Saunders denies this.

The purpose of supporting leftist groups was not to destroy or even dominate… but rather to maintain a discreet proximity and monitor the thinking of such groups to provide them with a mouthpiece so they could blow off steam. It was to be a beachhead in western Europe from which the advance of Communist ideas could be halted. It was to engage in a widespread and cohesive campaign of peer pressure to persuade intellectuals to dissociate themselves from Communist fronts. (Page 98)

Besides publishing, the CIA set up front groups for disseminating their ideas. In 1952 it began setting up dummy organizations for laundering subsidies. The formula was:

Go to a well-known rich person and tell them you want to set up a foundation in the name of the government:

- Pledge this person to secrecy.

- Publish a letterhead with the would-be name of the donor.

- Give the dummy organization a neutral sounding name.

When it came to the arts:

With an initial grant of 500,000 Laughlin launched the magazine Perspectives which targeted the non-communist left in France, England, Italy, and Germany. Its aim was not so much to defeat leftist intellectuals as to lure them away from their positions by aesthetic and rational persuasion. (Page 140)

According to Stoner Saunders the animated cartoon of Orwell’s Animal Farm was financed by the CIA and distributed throughout the world. But the CIA did more than distribute. They actually changed the story.

In the original text, communist pigs and capitalist man are indistinguishable, merging into a common pool of rottenness.

In the film, such congruity was carefully elided (Pilkington and Frederick, central characters whom Orwell designated as the British and German governing classes are barely noticeable) and the ending is eliminated. In the book:

The creatures outside looked from pig to man and from man to pig and it was impossible to say which was which. Viewers of the film saw something different — which was the sight of the pigs impelling the other watching animals to mount a successful counter-revolution by storming the farmhouse. By removing the human farmers from the scene, leaving only the pigs reveling in the fruits of exploitation, the conflation of the Communist corruption with capitalist degradation is reversed. (Page 295)

When it came to his novel, 1984, most everyone assumed that the idea of it came from Orwell’s Trotskyist criticism of Stalinism. However, Trotsky’s biographer, Isaac Deutscher, claimed that Orwell got the symbols, plot and chief characters from Yevgeny Zamyatin’s book We.

Who was involved?

What leftists or former leftists were involved in the Congress for Cultural Freedom? Sidney Hook (former Marxist), Arthur Koestler (former communist), James Burnham (former Trotskyist), Raymond Aron, Harold Laski, Isaiah Berlin, Daniel Bell (The End of Ideology), Irving Kristol (former Trotskyist,) Franz Borkenau (former communist), and Lionel Trilling to name just a few.

For the most part, without knowing exactly who they were dealing with, these former communists like Burnham, Koestler and Louis Fischer wanted to directly confront Stalinism politically. They felt no one knew better how to fight communism than they did. Burnham went so far as to say that CCF should form a true anti-communist front embracing the non-socialists right as well. Koestler, Burnham, Hook, Lasky and Irvin Brown met every evening as an unofficial steering committee. But cooler heads prevailed. Michael Josselson, one of the founders of the organization, believed in the soft-sell strategy, which is winning intellectual support for the western cause in the Cold War by fostering a cultural community between America and Europe.

Did these ex-communists know they were working for the CIA?

The parameters of knowing ranges from who knew and who didn’t. But these extremes are too easy. Better to separate points of gradation into:

- Those who knew everything about the CIA involvement;

- Those who knew some things and not others and did not want to find out;

- Those who thought some things were fishy but didn’t inquire further; and,

- Those who were completely naïve and didn’t know.

One who knew was Sidney Hook, who was in contact with the CIA. He was a regular consultant to the CIA on matters of mutual interest. In 1955 Hook was directly involved in negotiations with Allen Dulles. Another who knew but was not ashamed of it was Diana Trilling who said, “I did not believe that to take the support of my government was a dishonorable act”. Late in his life Orwell knew the CIA was involved and actively supported them. He had handed over a list of suspected fellow travelers to the Information Research Department in 1949.

Deeply suspicious of just about everybody, Orwell had been keeping a blue quarto notebook close to hand for several years. By 1949 it contained 125 names. (The Cultural Cold War, Page 299)

It would seem that most leftists fell into categories two and three. It is highly unlikely that those involved in radical politics both internationally and domestically, and those subjected to the intrigues of Stalin would be completely naïve about the machinations of any other large political organizations that were involved.

Furthermore, as Primo Levi points out insightfully in The Drowned and the Saved, those who consciously lie to others as well as themselves are in the minority:

But more numerous are those who weigh anchor, move off from genuine memories, and fabricate for themselves a convenient reality. The silent transition from falsehood to sly deception is useful. Anyone who lies in good faith is better off, he recites his part better, he is more easily believed. (The Cultural Cold War, Page 414)

How successful was the CIA?

It is tempting to think that an organization as powerful as the CIA would overwhelm and turn to mush another group that stood in its way. But that is not what happened. Ex-communists fought among themselves and twisted the intention of the CIA and took things in another direction. As if to answer Stoner Saunders’ excessive attribution of power to the CIA, Hugh Wilford says that the CIA might have called the tune, but the piper didn’t always play it, nor did the audience dance to it.

Did This Left Gatekeeping End with the Ending of the Congress for Cultural Freedom?

It is fair to say that Khrushchev’s revelations about Stalin broke the hearts and backs of The Old Left. The sad story of disbelief and denial of communists who spent years bending over backward justifying Stalinist terrors and show trials was exposed. The Congress of Cultural Freedom contributed to this downfall to some extent, though the whole operation was exposed by Ramparts Magazine in 1967.

But what about the New Left? Since the Congress of Cultural Freedom had ended, was there anything left to monitor? After all, the New Left was not Leninist. Is there a relationship between the characteristics of the New Left in Table I and some new monitoring organizations like foundations, think tanks, public relations campaigns and lobbyists? Or was the New Left an autonomous, spontaneous eruption of the youth culture of the 60’s? Part II will discuss these important questions.

• First published at Planning Beyond Capitalism