Orientation

The field of psychology is a big capitalist business, whether it is helping capitalists with advertising, finding new consumers, selling self-help books to an anxious public, or helping psychiatrists or counselors make a living off of people’s misery. There are six schools of psychology: psychoanalysis, behaviorism, humanistic psychology, cognitive psychology, physiological psychology and evolutionary psychology. While all these schools are different from each other, they all have in common stripping individuals from their social and historical identity and either ignoring it, suppressing it or are unaware of it. They then present this isolated, alienated individual of capitalist society as ground zero, as normal.

The purpose of these two articles is to suggest a psychological ray of hope for all socialists who have rightfully been suspicious of the field of psychology or those who have put up with therapists who tell them their problems are due to: a) lousy parenting; b) positive or negative reinforcement; c) conditional love; d) cognitive distortions; e) chemical imbalances in the body; f) evolutionary mismatches or sexual selection maladaptation. In other words, everything but cut-throat competition and capitalist irrationalities. How do socialists navigate our psychological problems when both the analysis and the remedies are all products of a capitalist society?

Lev Vygotsky is currently “hot stuff” in the field of American psychology. But as in the case of Freud, his work comes to the United States truncated and sanitized as it crosses the Atlantic. These “neoliberal” (Ratner) American psychologists praise the work of Vygotsky as the “father of cooperative learning” or discuss his learning theory as “zone of proximal development” solely in micro-interpersonal ways. They ignore the impact of macro-cultural forces like capitalism, state surveillance, propaganda, class stratification, anti-democratic politics or the prison industrial complex on psychological issues. These bourgeois psychologists either don’t know or actively suppress the reality that Vygotsky was a Marxist who wanted to build a communist psychology which is ontologically and epistemologically at odds with the social contract theory of society that these neo-liberal psychologists consciously or unconsciously support. As a Marxian psychologist in the Soviet Union Vygotsky set out to answer the question: what would a communist psychology look like?

This article will begin with a high contrast between what capitalist psychology is and what socialist psychology would be like in general. Secondly, I will contrast the differences between atomistic, organic and dialectical theories of human development in general. Third, I will contrast the developmental theories of Vygotsky to the well-known theories of the great cognitive psychologist Jean Piaget in childhood and adolescent development. This will be Part I.

In Part II I will show how socio-historical psychology can explain the psychological changes whole societies go through as the economy, the technology and the politics of society change. I will cover the work that Alexander Luria did with the Russian peasants to show how their perception, identity and cognition changed because of the revolutionary changes in Czarist Russia as Russia moved to be industrialized under socialism. Next I will discuss what a Marxian theory of the emotions looks like and how it contrasts with bourgeois theories of the emotions. Then I will discuss how socialist therapy would differ from bourgeois therapy. Under socialist therapy the group would be the basic unit of psychological transformation rather than the individual. Lastly, we will apply Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development not to learning opportunities in child development, which is what Neoliberal psychologists do, but how the zone of proximal development (renamed by one scholar “the zone of proletarian development”) helps us to understand revolutionary situations.

I Capitalist vs Socialist psychology

Capitalist psychology splits the individual from his social, historical and class identity. It takes the stripped-down, isolated, alienated individual as human nature and its point of departure. Socialist psychology connects the individual to the type of society we live under (capitalist), the historical period in which we live (a descendant phase of capitalism), and our social class location (upper-middle, middle or working class) as our point of foundation. Most every psychological problem is rooted in the chaotic nature of all three systems and how they interact.

Capitalists eternalize alien relations under capitalism and treat them as if they were always there. They project how people learn, think, emote and remember under capitalism into other historical periods. For example, they present narcissism, attention-deficit disorders or manic depression as present in tribal or state civilizations just as much as they are under capitalism. On the other hand, socialist psychology is historically sensitive to how changes in the political economy will create, amplify or destroy, narcissism, attention-deficit disorder or manic depression. Different social formations create different psychologies and different systems of health or pathology. Narcissism, the preoccupation with oneself and sense of entitlement, are products of capitalist society. In Colonial America there was no such thing as narcissism.

In socialist psychology, working class, middle class and upper middle class have different psychologies of emotion, thinking, remembering, love making or mental disturbances. There is a reason why working-class men and women die seven to ten years younger than middle classes. They are hammered into the ground early by the kind of work they do, the neighborhoods they live in and their eating and drinking habits. In capitalist psychology social class is ignored. Psychological theories, whether cognitive, humanistic, physiological or evolutionary act as if class doesn’t matter. Bourgeois psychology will reluctantly cede ethnic or gender differences as a result of the political work done by liberals in the past but last 50 years. But Yankee psychologists either ignore social class or assume that there are three social classes, upper, middle and lower middle. This is a 70 years out-of-date stratification system. Sociologists today agree there are at least 6 social classes and they are deeply graded.

Capitalist psychology treats human consciousness as if it were separate from human practice. In other words, what people do for a living and how their work affects them has no serious bearing on their sense of awareness. States of consciousness are treated as if the individual were free to be aware of whatever they want. In socialist psychology what a person does in work over and over again affects and shapes the parameters of their consciousness. All consciousness is class consciousness.

Every social class lives in a little micro-bubble of reality. A working-class person inhabits a world of religion, community, recreational habits, child-rearing and occupational awareness that is rooted in wage labor. A middle-class person experiences world of religion, community, recreation, music, child-rearing and occupational habits from a salaried professional viewpoint. Crossing states of consciousness is awkward because class states of awareness are different. This is why attempts by “human resources professionals” to get social classes to mix at company picnics rarely turns out well as middle managers will change tables and sit with other middle managers and cashiers and factory workers will disrupt attempts to integrate classes at tables and will sit with members of their own social class.

Capitalist psychology assumes people are fundamentally selfish, as if we individuals are like Hobbes’ atoms, greedy, insensitive, grasping and mindlessly crashing into each other. Whether it is Freud’s ego or the behavioral motivation of pain or pleasure, individuals’ primary motivation is self-interest. A socialist psychology understands people are primarily collectively-creative. This is demonstrated when workers are given the opportunity to operate cooperatives, create workers councils in revolutionary situations or even during natural disasters. Selfishness is a product of capitalism and not the primary way human beings operate.

The contradictions within capitalist economic relationships are visited on the emotional life of its individuals. Capitalist divide-and-conquer strategies create racism on the job by giving privileges to white workers to keep them from uniting with minorities for better pay. Capitalists expect loyalty to sports teams even when the owners move the team away and the players sell themselves to the highest bidder. Capitalists expect working-class loyalty to a nation and for them to fight wars, while capitalists exercise no loyalty to workers when they relocate in another nation where the costs of labor and land are cheaper. In socialist psychology where the forces of production (technology and methods of harnessing energy) and the relations of production (the political economy) are harmonious human beings are not pulled and pushed in opposite directions.

In capitalist psychology the intelligence of people is determined by tests which ask individuals to answer questions on an IQ test. This ignores the fact that most real-life situations occur at work where people’s intelligence is harnessed by having to cooperate with others. For Vygotsky, true intelligence is measured first by their cooperative relationship with people at work before they have internalized the skills. Intelligence is further tested when they apply what they have internalized at work to non-work situations, such as play or artistic or scientific endeavors outside of work. Vygotsky called this cooperative learning the “zone of proximal development”.

In capitalist psychology the unconscious is personal. What is unconscious is a history of what is behind the scenes in an individual’s personal life. In Freud’s case, that would be a painful past. For a socialist psychology what is unconscious, at least for the working class, is a “social” unconscious. It is the repressed collective creativity of the human past, dead labor, that causes this individual to have “social amnesia”. The wisdom that has accumulated from revolutionary situations: the heroic stance of the Paris Commune; the heroism of Russian factory councils and the workers’ self-management experiments in Spain from 1936-1939. All this is blocked from the individual. To make this social unconscious conscious is to make the working class shapers of history rather than just being a product of it.

In capitalist consumption, commodities are fetishized. Commodities acquire a life of their own and oppress the very people who created them. Capitalist psychology has nothing to say about this. Besides Wilhelm Reich, Erich Fromm is the only psychologist in any of the six schools of psychology I know who attempted to create pathological category of neurosis called “the marketing type”. Most capitalist psychologists accept accumulation of commodities and capitalist mania for accumulation as not worth capturing as a diagnostic category.

For a socialist psychology, our work – collective creative activity – is the very process that makes us human. It can raise us to heaven (under socialism) or condemn us to hell (life under capitalism) but there is nothing neutral or private about it. Meaningful work is what makes us most human. For capitalist psychology, work is just something to either put up with or derive private pleasure from. Life for bourgeois psychologists begins when an individual has leisure time. Work under capitalism still possesses a religious root of the result of original sin.

For capitalist psychologists’ individuals have free will and they more or less freely choose their situations. Religious institutions, educational manipulation, propaganda, legitimation, mystification and collusion in oppression is completely Greek to them. For socialist psychologists all these forms of socio-political control affect free will. While none of these processes by themselves or even all together determine a person’s free will, the options people choose to exercise are significantly constrained.

Lastly, speaking therapeutically, capitalist psychology glorifies the private relationship between the individual and the therapist. The individual’s private world is best handled away from other individuals. This, despite the research that says group therapy has a better success rate. In a socialist psychology theory the group is not just a witness to the drama of the individual. Rather it is the vehicle for individual development. Socialist psychology encourages individuals to find their lost group identity and to learn that through cooperation in groups personal problems can be either gotten rid of or minimized. More of this in Part II.

II Theories of Development: mechanistic, organicist and dialectical

Any theory of human development must consider the relationship between biological processes (the brain), psychological processes (the mind) and social structures and processes. In this section I have followed the work of Jonas Langer (Theories of Development); Klaus Riegel (Psychology, My Love); Heinz Werner’s Comparative Theory of Mental Development, and lastly, Valsiner’s book on Werner (2005).

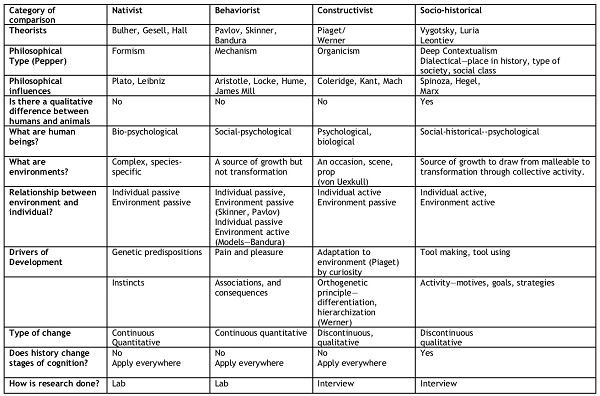

There are four major theories of human development. The Freudian psychoanalytic theory is not included here because most of Freud’s theory has been either proven wrong or it has not been subjected to scientific experiment. Of the four theories, nativist, behavioral, constructionist and socio-historical, the first three come out of bourgeoisie psychology which began at the end of the 19th century. Only the last theory is socialist.

This first theory, nativism, goes as far back as the turn of the century. Nativists have argued that heredity and genetic predispositions are primarily, if not exclusively, the drivers of human development.

Later, evolutionary psychologists (Cosmides and Tooby) have added a more dynamic approach by specifying the evolutionary reasons why some behaviors are more adaptive than others. All nativists see change as gradual and continuous. Gesell, Buhler and Hall would emphasize that the individual is passive (genetically determined) and the environment is passive because it takes generations before new adaptive skills are required. Since most nativists don’t have specific stage theories, I include them to show that not all psychological theories even contend that stages exist. In Pepper’s book, World Hypothesis, nativist theories are classified as “formist” with its philosophical roots in Plato and Leibniz.

The second theory, radical behavioristic theories of development, is mechanistic. Whether it’s Pavlov or Skinner, they see the individual (whether their focus is the brain or the mind) as passive and an environment as relatively passive. This environment either conditions responses resulting from past associations (Pavlov) or the environment rewards or punishes the individual (Skinner). But the environment for the behaviorist operates at a micro level of family, friends, teachers, or school-mates. The environment for behaviorists is not macro-social institutions such as capitalism or an authoritarian state. These theories are called mechanical theories of growth because:

- they emphasize what is going on external to the individual;

- see change as gradual and quantitative adaptations to external conditions;

- the individual mind, brain or body is a blank slate which doesn’t bring in anything active in the interaction with the environmental slate; and,

- the whole is a product of the build-up of the parts.

Langer has called these theories the “mechanical mirror” theories because the goal is for the individual to ideally reflect the environment. Its philosophical roots are in Aristotle as well as Locke’s association theory. Like the nativists, behaviorist theories have no stages.

A variant of the second type of behaviorism is Bandura’s social learning theory. This theory sees the environment as active and the person as passive. Bandura argues about the power of social models – attractive, powerful and having expertise in shaping the individual. This kind of theory would be a mechanical materialist, one in which individuals are seen as victims of social circumstances not of their choosing. In sociology, Durkheim’s description of the movement from mechanical to organic society historically might be an example because the individual appears as a passive victim of the division of labor in society. In geography a mechanical materialist attitude would be the environmental determinism of Ratzel, which says that the climate and geography directly impact how the individual turns out.

The third type of theory emphasizes the active person and a relatively passive environment. Since the work of Piaget on cognition will be considered in depth in the next section, there is no point in describing it in detail here. Meaning-making is confined to changes in internal states, while the objective world is passive, a prop for a psychobiological drama staged within the body of an individual. Social mediations such as teachers, media, religion are secondary.

Heinz Werner is another “organic” developmental psychologist who saw a child going through predictable stages. In the first stage of child development, there is a primitive globalism, a whole without parts. The child in a global primitive state does not make a distinction between the objective and the subjective worlds. Boundaries are fused. Boundaries are porous between:

- dreams and imagery;

- percepts and outer reality;

- physical body and the objects in the world;

- names of things and the things themselves; and,

- motives for doing something and actions.

In this primitive globalism, space has no objective properties and is inseparable from the objects or people within the space. In terms of time, children at first cannot tell the difference between objective time passing as measured by clocks, and subjective time which speeds up or slows down based on the level of interest. This primitive fusion is also characterized by rigidity and instability in its functions.

As part of the developmental process, these states of fusion are followed by a stage of differentiation in which the objective characteristics of the physical world are clearly separated from the subjective experiences of the individuals. This leads to a stability and flexibility in their functions. After gaining the capacity to tell the difference between the objective and subjective world, a new whole can be created, but this time it is a complex whole with fully differentiated parts.

Werner was very bold in his claims, arguing that the similar patterns can be comprehended not only in the differences between younger and older children, but also in the development of primates; the difference between abnormal and normal adults; and even the difference between people in primitive societies and modern societies. If Werner’s theories were applied to the subject matter of history, he would say that in the Middle Ages there was a primitive unity in outlook. The sense of space, time, cause, human identity was formerly a similar parallel with the fused state of consciousness of a child. Beginning in early modern Europe, societies would be characterized by gradual separation between the objective world and the subjective world. This third theory is organic because:

- development is seen to be an unfolding process of a plan which is internal to the organism;

- the stages an individual goes through are qualitatively different from each other and go through accumulating levels of complexity; and,

- there is a primitive whole right from the beginning. From there, differentiation takes place, resulting in a new, more complex whole.

Werner’s theory can be categorized by Pepper as “organicist” with its philosophical roots in Kant and Mach.

The fourth way of thinking of development is the dialectical approach. Here the environment is active and the person is active. This is typified in the work of Vygotsky, Luria and Leontiev. Compared to the dialectical theory, the mechanical and organic theories attitude towards interaction is weak. All those theories say either the individual is active or the environment is active. But what they all have in common is that the interaction between the environment and the person is not co-creative. The subjective and objective systems are self-subsisting and only interact through accidental or in a predetermined way, not in a self-organizing way.

The active-active stage of dialectical development is the only one in which both the social world and the individual co-create each other. On the one hand, social forces produce individuals, but those individuals, through their work, reproduce social forces. The individual is first the yarn and then becomes the weaver of social life. The individual-social relationship is not static. It evolves into a spiral, either getting better or worse but never staying the same over the course of history. This is what socialist psychology is all about!

Please see the table at the end of the article for a summary.

III Stages of Cognitive Development: Vygotsky vs Piaget

Similarities between Piaget and Vygotsky

Piaget and Vygotsky had important similarities. They both opposed the behaviorists’ reduction of consciousness to “behavior”. So too, they opposed nativists’ reduction of human consciousness to instincts. At the other end, while both were sympathetic to the Gestalt theory of perception in which human consciousness was a whole which was more than the sum of its parts, they both criticized it as being static. Both Piaget and Vygotsky felt Gestalists ignored human consciousness as developing. Both Vygotsky and Piaget claimed that there were qualitative leaps between levels of development.

Furthermore, they both asserted that cognitive development was rooted in actions and could not be simply something that goes on inside the body or the mind of the individual. Second, they both agreed that actions were driven by goals, unlike the behaviorists who believed “behavior” was driven by associations and consequences, both of which came from external forces. Third, Piaget and Vygotsky were both dialectical. They explained development processes as a result of multiple causation where what was once a cause becomes an effect. This was opposed to looking for a single cause. Fourth, each was skeptical of what research on human beings could achieve in a lab. Both used interviewing techniques. Fifth, both did not think much of intelligence testing in formal settings for different reasons. Lastly, both were interdisciplinary. Piaget started as a biologist before he became a psychologist and he never put these disciplines aside in his psychological work. As for Vygotsky, before becoming a psychologist, he was an art critic and a producer of plays.

Differences between Piaget and Vygotsky

Vygotsky and Piaget had many differences. For one thing, each came out of radically different philosophical traditions. Piaget was most influenced by Kant and Ernst Mach, while Vygotsky’s influences were Spinoza, Hegel and, of course, Marx and Engels. They also disagreed over the nature of human beings. Piaget saw human beings as primarily bio-psychological creatures. He once said that prior to the ages of 7 – 8, children didn’t have much of a social life. Vygotsky saw human beings as primarily socio-historical beings right from birth, with biology only setting the necessary conditions.

The third difference has to do with the relationship between language and thought. Piaget argued that language was a product of cognitive maturation, an add-on after thinking is completed. Vygotsky saw language as a mediator for the completion of thought. Fourth, Vygotsky and Piaget saw the role of adults and schooling very differently. Piaget trusted children to spontaneously learn new things and that adults were just background sources providing a setting in which children learned. The same relationship was played out in schools. Vygotsky argued that, left to their own devices, children are not spontaneously curious. It takes adults to get the ball rolling. Children only sustain curiosity when adults take center stage first. In the case of schooling, Vygotsky argued that without school, scientific concepts cannot be learned. Children do not naturally learn to think more scientifically as a product of maturation.

Fifth, in the relationship between learning and development, Piaget emphasized that maturation leads to learning. For him, learning is a secondary process which occurs later in time. For Vygotsky, cooperative learning through the zone of proximal development is the leading edge of maturation. Our biological nature becomes background and the older we get, the more our social learning takes over.

Each had theories of cognitive development. Piaget’s stages were sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational and formal operational. Vygotsky, in his book Thought and Language, argued that children go through four cognitive stages: syncretism, complexification, graphic-functional and categorical deductive. A comparison of these stages shows considerable overlap,

There are many other differences, but these differences center around child development, whereas I want to turn to the subject of history. For our purposes, the most important difference between Piaget and Vygotsky centers around whether the stages of cognitive development are affected by history. Piaget argues in Psychogenesis and the History of Science that his four cognitive stages of development are not affected by social evolution. All four of his stages will unfold inside the individual, regardless of whether the society is composed of hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists, members of agricultural states, herders or members of industrial capitalist societies. Vygotsky and his colleagues Luria and Leontiev disagreed. Luria did research on the impact of the Russian Revolution on peasants. In the late 1920’s, he found that peasants underwent profound changes in perception, how they categorize, their concepts of self and cognition. He found changes in cognition from thinking complexes, to the graphic-functional to categorical-deductive stages as peasants moved from the countryside to the cities. More of this in the second part of this article soon to come.

Piaget’s four stages have stood the test of time. While the ages that children and adolescents go through these stages are not what Piaget originally proposed, the sequence of the stages as well as their contents have held up. As for Vygotsky and Luria’s work, the work of a group in Russia whom Yuriy Karpov calls “Neo-Vygotskians” (The Neo-Vygotskian Approach to Child Development) does not follow up on Vygotsky’s and Luria’s stages of cognitive development. In addition, it is far more difficult to find research from Russia where most of his Marxian followers are likely to be. Many of the books have not been translated from Russian to English. In addition, if the books have been published, they are extremely expensive for an author no longer affiliated with an educational institution. Lastly, Vygotsky and his colleagues were in and out of trouble with Stalin and it is hard to know how much of their research has been lost, suppressed or marginalized.

IV Retrospect and Prospect

In Part I of these articles I have introduced a side of Lev Vygotsky that most Yankees know nothing about. He was a Marxist who sought to build a communist psychology. I have contrasted capitalist to socialist psychology across eleven categories: psychological disorders, social class, consciousness, motivation, emotions, intelligence, the place of the unconscious, consumptive patterns, work, free will and therapy. Lastly I compared socialist dialectical human development to the nativistic, mechanistic, organicist theories. Lastly, two great psychologists of development were compared: the constructionism of Piaget to the socio-historical psychology of Vygotsky.

But what crisis was going on in the field of psychology in the mid 1920’s that made Vygotsky intervene? What was Luria trying to prove when he went into peasant villages during the Russian Revolution to test their sense of self, their perceptions and their reasoning? In bourgeois psychology emotions are a big deal. We are told we are repressing them, need to get in touch with them or share them. Emotions are understood as the sacred private property of individuals. They are in our guts, or for the cognitive psychologists in our minds. Socialist psychologists think neoliberal psychologists are looking in the wrong place for our emotions. For us, emotions are socially constructed, class-based and change over the course of history.

When it comes to bourgeois therapy, the capitalist political economy, commodity fetishism and alienation are nowhere to be found in their analysis. At best people enter group therapy not because research shows it works better than one-on-one, but because it is cheaper. It is clearly a second choice. For socialist psychologists, the collective creativity of the group not only helps to solve individual problems but it is the key to reducing all problems in capitalist society.

What happens to people during revolutions psychologically? Research in mass psychology shows both increased anxiety and increased joy accompanies building barricades, taking over workplaces and throwing Molotov cocktails. Can Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development explain what is going on here? In the second part of this article we will find out.

Theories of Ontogenetic Development

• First published in Planning Beyond Capitalism

• First published in Planning Beyond Capitalism