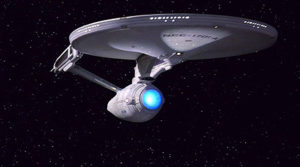

I grew up with the idea that leaving Earth was inevitable. The Space Age had arrived and the sky was no limit. Per ardua ad astra was no longer a metaphor; it would happen, it was happening. Invisible radiation traveled through the air every afternoon to bring me indelible images of humans in space, benignly, bravely venturing out into the numinous beauty of the galaxy strung with stars, enticingly intercalated with exotic life. A chorus of ethereal voices accompanied their stalwart ship each time, as it boldly went where no man [sic] had gone before.

I grew up with the idea that leaving Earth was inevitable. The Space Age had arrived and the sky was no limit. Per ardua ad astra was no longer a metaphor; it would happen, it was happening. Invisible radiation traveled through the air every afternoon to bring me indelible images of humans in space, benignly, bravely venturing out into the numinous beauty of the galaxy strung with stars, enticingly intercalated with exotic life. A chorus of ethereal voices accompanied their stalwart ship each time, as it boldly went where no man [sic] had gone before.

What it carried with it were clean, comfortably-appointed living spaces where slim, attractive people sported glittery, form-fitting synthetics and teased and pomaded hair that was preternaturally perfect. Mutual respect, affection and humor were their mainstays. There was racial harmony – for humans had united, at last! (Often against other species, but only if they threatened us first. Otherwise, we sought to befriend them.) Artificial intelligences informed, protected and consoled us, but knew their place, like good housemaids. If they overstepped, we pulled the plug. Our marvelous cultural diversity was still intact no matter how deracinated our existence had become, speeding along in a vacuum, light-years from home among the stretched-out stars.

Earth had figured it out. Humans had figured it out. We had solved all the challenges on our home planet, and now – on to the final frontier!

I was so happy in that promised land, as a child. I was happy being Lost in Space or going on a Star Trek, from the safety of the Danish modern sofa strewn with throws and pillows I made into a kind of cocoon. The living room always a comfortable 70 degrees, whatever was happening on the planet’s surface outside. I lived in a space craft, protected from the debilitating atmosphere of an alien world – my own.

My physical relationship to the biosphere surrounding my spaceship house, which silently and imperceptibly sustained it all, was limited; I spent most of my time indoors. And even out of doors, that relationship was always mediated. Not so much by technology or gear, as it is for bourgeois children (and adults) today, but a state of mind that was omnipresent, and which has facilitated the exponentially increasing reliance on complex technology that characterizes my personal timeline. I wasn’t staying inside because I was sickly or frail, but because I was afraid.

My family lived in pleasant college towns, not wilderness, human-made or otherwise. I was a member of the most protected class in the most protected country, judged by wealth and weaponry, in the history of the world. And yet that was not enough to be safe, ever.

Outside my spaceship were dangers, just like in the shows. They lay in wait everywhere, although within the hedge and fence-bound yard, I was still tethered, at least, to the life-support systems onboard. The woods beyond the fence (a disused orchard gone wild) were off-limits. We were told there was an abandoned well somewhere back there – we could fall in and drown. There might be snakes, foxes, feral dogs or rabid raccoons. In summer, enormous moths battered the spaceship’s plate glass windows in inexplicably suicidal, desperate, but somehow menacing swarms. June bugs flung themselves like stones against the screen doors. Burrowing creatures scratched at the concrete foundations. In winter, when I went out into the snow, I wore a puffy, full-body suit with attached boots and gloves, like an astronaut.

Other children, were, of course, the most dangerous element of all. We had lived in three different places before I was six; the neighborhood children were not just strangers, they were an alien race. When spring came, I climbed a willow tree in the yard, and from there I had a vantage point; I could perceive the approach of any threat. I have no sense of actually comprehending that tree as a living thing; it might have been a watchtower made of plank and steel. I would sit on the roof of the carport in the same way, watching for movement, wishing for a jetpack that could hoist me aloft, let me fly to safety if the aliens spotted me. I just wanted to escape. Wherever I lived as a child, I wanted to be somewhere else. I achieved escape velocity only through television.

My grandfather spoke proudly of having been born in the era of the horse and buggy and living to see the advent of the Space Age. For a settler-colonialist-descended people such as we, there was no finer description of progress: our mobility, our expansion could now go on forever. And yet somehow, when that triumphant July day rolled around, it was less real and compelling to me than the dullest Jetsons episode to hear the grainy epigram (“one small step for man…”) or see actual boot prints on the barren moon. And the erection of that flag, the same one that was then flying atop gunships plying Southeast Asian seas, overseeing an escalating slaughter in a burning jungle; just another story the television told us at night.

My grandfather spoke proudly of having been born in the era of the horse and buggy and living to see the advent of the Space Age. For a settler-colonialist-descended people such as we, there was no finer description of progress: our mobility, our expansion could now go on forever. And yet somehow, when that triumphant July day rolled around, it was less real and compelling to me than the dullest Jetsons episode to hear the grainy epigram (“one small step for man…”) or see actual boot prints on the barren moon. And the erection of that flag, the same one that was then flying atop gunships plying Southeast Asian seas, overseeing an escalating slaughter in a burning jungle; just another story the television told us at night.

The moon, a living goddess, a smiling benefactress in so many tales, was only a lifeless rock covered in gray dust. Now we knew. Now it had been proven.

What was the dark energy that powered the Space Race anyway? And planted that flag to hang in listless isolation on that spiritless plain? What was its political engine? It was the Cold War, with its sharp foretaste of nuclear annihilation, the capability we had recently acquired to destroy not just ourselves but all life on earth – even, potentially, the earth itself. In our fear-filled quest for safety through domination of the material world, humans had with bottomless irony achieved a state in which we would never be safe again. Now we had a lot more to fear than fear itself.

One night when I was ten or eleven, not long before the moon landing, Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove was on TV and we were allowed to watch it. “They’re too young,” my mother moaned. “They should know about this,” my father intoned. So, we watched, utterly baffled. At the end, a bunch of crazy things happened: Slim Pickens whooped as he rode that descending warhead, Peter Sellers marveled as he stood up from that wheelchair, and then suddenly there were bombs going off one after another, nuclear bombs, with a woman singing a sentimental song in the background. The End. WTFH? And yet at some level we children knew it was the end of the world. My brothers and I got fractious and started whining and fighting afterward. (When Dr. Strangelove had, much later, become one of my memorized films, I would remember “Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here, this is the War Room!”) “You see,” said my mother to my father. “I told you.” I couldn’t fall asleep that night. There was no safety. Rockets didn’t carry you to new worlds in interstellar space; they fell to earth. And when they did, everything blew up.

I didn’t know I was white then; my milieu, the liberal intelligentsia, was open to many socially progressive thoughts and ideas and still as racially circumscribed as any reactionary’s. But while I breathed the rarefied air inside my spaceship, Gill Scott-Heron was singing bitter poetry about the moon landing; he told how the America that lives in the shadows of racialized poverty watched that feat with a jaundiced eye.

A rat done bit my sister Nell

Her face and arm began to swell

(but Whitey’s on the moon)

Was all that money I made last year

(for Whitey on the moon?)

How come there ain’t no money here?

(Hmm! Whitey’s on the moon)

The year before Apollo landed was the fateful fork: cities had burned when Dr. King was murdered, martyr to a dream that turned out to be a fantasy, the peaceful realization of equality not by shiny idealized people out in space someday, but on this earth now.

Our only great prowess was technological. In no other way had we triumphed. We hadn’t solved anything on earth before launching ourselves into space.

And yet, without even straying from the yard, I can also recall that my childhood held the smell of turned earth, damp leaf mold, lilacs, pine duff, incipient rain. The feel of an onrushing summer storm, of the air as it seems to undergo a phase change. The almost sub-conscious morning and evening soundtrack of bird and insect song, frogs in the ponds and creeks. The minnows darting at the edges of the lakes we ventured in to swim. The alien world was there, at the exurban fringe, wilder (even after 300 years of settler-colonialist unconcern for intact ecosystems), more varied and fantastical than the wildest fantasies of life on other planets, if you just raised or lowered your eyes to it. One cubic inch of earth’s soil, says E.O. Wilson, contains more living organisms than the rest of the solar system combined, so far as we can tell.

Why were we schooled, long before television or space travel came along, to pay so little attention to this? To be so indifferent? Why were we so afraid of this that we ran into the arms of an unending nightmare?

Remaking authentic communities into packaged forms of themselves, re-creating environments in one place that actually belong somewhere else, creating theme parks and lifestyle-segregated communities, and space travel and colonization—all are symptomatic of the same modern malaise: a disconnection from a place on Earth that we can call Home. With the natural world—our true home—removed from our lives, we have built on top of the pavement a new world, a new Eden, perhaps; a mental world of creative dreams. We then live within these fantasies of our own creation; we live within our own minds. Though we are still on the planet Earth, we are disconnected from it, afloat on pavement, in the same way astronauts float in space. – Jerry Mander, In the Absence of the Sacred

Almost fifty years since, while racialized inequality has skyrocketed, an incalculable diversity of the planet’s biome has been reduced to livestock, monocrops and humans, and the global climate is on the verge of chaos. Now another dark, annihilating vision drives the contemporary fantasy of space colonization: the uninhabitable earth. Pick your poison: quick (nuclear war) or slow(ish): diminished, sweltering, lifeless continents surrounded by acid seas. Before he died, Stephen Hawking warned: this is the most dangerous time in the history of humanity, because we have acquired the capability of destroying the planet without being able to escape it.

This from a man kept alive for decades by mechanical intervention, who studied the most abstract objects in the universe, where the laws of physics themselves break down. A man who had no reason to love the living earth that gave him the genetic makeup that caused his body to start destroying itself in early adulthood. The perfect example of the expert: one whose unsurpassed sophistication and mastery of complex thought in one area, theoretical physics, was combined with an almost childlike simplicity where biological systems or social relations are concerned. This was a man who loved Star Trek too.

His remedy was not that we retreat, respectfully, from the disaster we have caused, and humbly use millennially acquired knowledge to try to repair something of what we have broken before “biological annihilation” becomes terminal. It was that we redouble our efforts to achieve escape velocity as soon as possible.

Escape we must, then, somehow, if he said so. There Is No Alternative, just as we are told about neoliberal capitalism, artificial intelligence, bioengineering, industrial agriculture, drone warfare, and (up next) geoengineering. We must keep up the 10,000 year-long attempt to transcend the biosphere and its constraints, because otherwise we won’t be free.

Dreaming of the key, each confirms the lock, said T.S. Eliot.

How free is anything to which there is no alternative?

Not long before he died, John Trudell, American Indian Movement activist and poet, came to San Francisco (on whose high-priced pavement I’ve been afloat for over two decades now, lucky me). He spoke prophetically, an ancient role, ignored then as now – or we wouldn’t be in this Groundhog Day-like predicament, facing the endemic prospect of civilization’s collapse, again. A defining characteristic of civilizations, right up there with walls, writing, agricultural surplus and standing armies, must be that they ignore their prophets. Trudell said something shocking to anyone steeped in Western liberalism: “I don’t trust that word, ‘freedom.’ To me, there is no such thing as freedom, there is only responsibility.”

This whole question of freedom and frontiers (which have nothing to do with borders, that’s another essay) is etched deeply into the settler-colonialist psyche. Television programming from my generation forward has been the equivalent of myths and tales told around the fire, and it’s easy to find examples from my youth of how this worked in practice. I think of the popularity of Westerns, waning as I grew. They were the final abstraction of the American frontier, transmuted into the dimensionless landscape of broadcasting when it no longer existed in the physical world. Those free lands that once must have seemed infinitely vast, by now ensnared in a stale gray net of concrete, another project made necessary by the Cold War: the completion of the interstate highway system. Once the frontier was officially “closed” in the 19th century, civilization had encircled the globe and there was nowhere else to go but up. The ensuing hot wars gave us the technology, the Cold War gave us the drive. And so, the space race and Star Trek, its consumer-friendly mythology, were born.

But what if you were forced to work the land, and freedom meant freedom from it? Leah Perriman of Soul Fire Farm describes the work of re-forging a link broken in this nation by chattel slavery. She says of Black Americans: “We have confused the subjugation our ancestors experienced on land with the land herself, naming her the oppressor and running toward paved streets without looking back. We do not stoop, sweat, harvest, or even get dirty because we imagine that would revert us to bondage.”

She goes on to describe a student first resisting, then allowing himself to experience for the first time the sensation of his bare feet on the earth, the almost electric charge that goes through him as another past is recovered, one that could be transformative if it were accessed collectively.

While billionaires like Musk and Bezos are literally shooting into space the surplus value extracted from workers and the earth, others are trying to sink their bare feet back into the ground. But the ground is shifting so fast now, and more of it is being covered by cement or blown off in dust storms or washed into the oceans every day. Is it too late to re-establish roots? To put aside a specious, emptied out “freedom,” and take not just individual but collective responsibility, once and for all? Will enough people relinquish their deadly privilege, will enough of the global bourgeoisie turn from the hamster-wheel of consumption and throw their lots in with repair and reparations? Before…what?

Too late isn’t the right way to frame the question; there’s no such thing till after the fact. Millions will try/are trying to make these changes, but only a generalized humility, not human exceptionalism, might guide them to success – by which I mean meaningful survival. Processes are in motion of which we are only barely becoming aware; they are larger than our global civilization, they are older than our species. We are not in charge. We only ever dreamed we were, anyway, just as we only ever dreamed we could be “free” of the earth or one another.

Dreaming of freedom without collective responsibility created the lock, built the progress trap, strengthened the feedback loop of capital, technology and consumption. And fear of the Other, human or not, fired the pursuit of safety that is killing the world. Even if we could achieve escape velocity as a species, we would be bringing all of that right along with us.