Following Parts 1, 2, 3 and 4 of the World of Resistance Report, in this fifth installment I examine the warnings of social unrest and revolution emanating from the world’s major international financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank, as well as the world’s major consulting firms that provide strategic and investment advice to corporations, banks and investors around the world.

These two groups – financial institutions and the consultants that advise them – play key roles in the spread of institutionalized corporate and financial power, and as such, warnings from these groups about the threat posed by “social unrest” carry particular weight as they are geared toward a particular audience: the global oligarchy itself.

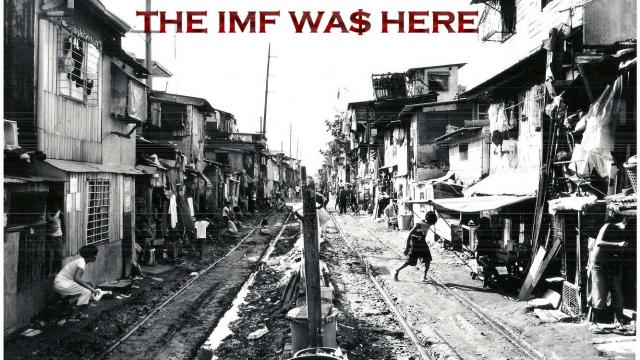

Organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank were responsible for forcing neoliberal economic “restructuring” on much of the developing world from the 1980s onwards, as the IMF and E.U. are currently imposing on Greece and large parts of Europe. The results have been, and continue to be, devastating for populations, while corporations and banks accumulate unprecedented wealth and power.

As IMF austerity programs spread across the globe, poverty followed, and so too did protests and rebellion. Between 1976 and 1992, there were 146 protests against IMF-sponsored programs in 39 different countries around the world, often resulting in violent state repression of the domestic populations (cited explicitly by Firoze Manji and Carl O’Coill in “The Missionary Position: NGOs and Development in Africa,” International Affairs, Vol. 78, No. 3, 2002).

These same programs by the IMF and World Bank facilitated the massive growth of slums, as the policies demanded by the organizations forced countries to undertake massive layoffs, privatization, deregulation, austerity and the liberalization of markets – amounting, ultimately, to a new system of social genocide. The new poor and displaced rural communities flocked to cities in search of work and hope for a better future, only to be herded into massive urban shantytowns and slums. Today roughly one in seven people on Earth, or over 1 billion, live in slums. (An excellent source on this is Mike Davis’s Planet of Slums.)

How the Big Institutions Have Operated

Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize-winning former chief economist at the World Bank, blew the whistle on the World Bank’s and IMF’s policies in countries around the world – an act for which he was ultimately fired. In an interview with Greg Palast for the Guardian in 2001, Stiglitz explained that the same four steps of market liberalization are applied to every country.

The first includes privatization of state-owned industries and assets. The second step is capital market liberalization, which “allows investment capital to flow in and out,” though as he put it, “the money often simply flows out.” As Stiglitz explained, speculative cash flows into countries, and when there are signs of trouble it flows out dramatically in a matter of days, at which point the IMF demands the countries raise interest rates as high as 30% to 80%, further wrecking the economy.

At this point comes step three, called “market-based pricing,” in which prices get raised on food, water and cooking gas, leading to what Stiglitz calls “Step-Three-and-a-Half: the IMF riot.” When a nation is “down and out, [the IMF] squeezes the last drop of blood out of them. They turn up the heat until, finally, the whole cauldron blows up.” This process is always anticipated by the IMF and World Bank, which have even noted in various internal documents that their programs for countries could be expected to spark “social unrest.”

And finally comes step four, “free trade,” meaning that highly protectionist trade rules go into effect under supervision of the World Bank and World Trade Organization.

Expecting Riots

The term “IMF riots” was applied to dozens of nations around the world that experienced waves of protests in response to the IMF/World Bank programs of the 1980s and 1990s, which plunged them into crisis through austerity measures, privatization and deregulation all enforced under so-called “structural adjustment programs.”

As the Guardian noted in September of 2012, “the European governments are out-IMF-ing the IMF in its austerity drive so much that now the fund itself frequently issues the warning that Europe is going too far, too fast.” Thus, we saw “IMF riots” – protests against austerity and structural adjustment measures – erupting over the past three years in Greece, Spain, Portugal and elsewhere in the E.U.

An academic study published in August of 2011 by Jacopo Ponticelli and Hans-Joachim Voth examined the link between austerity and social unrest, analyzing 28 European countries between 1919 and 2009, and 11 Latin American countries since 1937. The researchers measured levels of social unrest looking at five major indicators: riots, anti-government protests, general strikes, political assassinations and attempted revolutions.

The verdict: The researchers found there was “a clear and positive statistical association between expenditure cuts and the level of unrest.” In other words, the more that austerity was imposed, the more unrest resulted. Spending cuts, they wrote, “create the risk of major social and political instability.”

The Eurozone has been referred to by some as “an unemployment torture chamber” due to the structural reforms to the labor market – enforced through bailout conditions – which were purportedly designed to make it easier for employers to hire and fire but, instead, “firing has utterly dominated the employers’ agendas,” according to the Globe and Mail. This has created a “lost generation” in which unemployment in the E.U. for youths between 16 and 24 amounts to roughly 25% – while in Italy it’s roughly 40% and for Greece and Spain it’s as high as 60%. Tom Rogers, an adviser to Ernst & Young, noted, “Youth joblessness at these levels risks permanently entrenched unemployment, lowering the rate of sustainable growth in the future.”

The head of the IMF, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, warned in 2008 that “social unrest may happen in many places, including advanced economies.” The head of the World Bank, Robert Zoellick, warned in 2009 that “If we do not take measures, there is a risk of a serious human and social crisis with very serious political implications.”

Additionally, in November of 2009, the IMF chief warned the premier British corporate lobbying group, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), that if a second major bailout of the banks were to occur, democracy itself would be jeopardized. The “man on the street” would not accept further bailouts, Strauss-Kahn said, and “the political reaction will be very strong, putting some democracies at risk.”

Consulting in the Midst of a Crisis

Global consulting firms play a peculiar role in the global economic order. The consulting, or “strategy,” firms became commonplace in the 1960s onward, and were frequently seen as “home to some great minds in the corporate world,” hired by corporate, financial and other institutional clients to advise management on strategy and investments. The Financial Times referred to the industry as “a global behemoth, employing an estimated 3 million people and generating revenues of $300 billion a year,” with the industry’s “product” being “the knowledge vested in its people.”

According to an Oxford team of researchers, in 2011 consulting firms advised on more than $13 trillion of U.S. institutional money. Worldwide, consultants advised roughly $25 trillion worth of assets. Consulting advice was seen to be “highly influential” in the United States; yet despite the enormous power wielded by consultancy firms, the Oxford study found that the funds recommended to investors by consultants did not in the end perform better than other funds.

Still, the influence of giant consulting firms remains, although their reputations have taken some hits along the way. The world’s largest consulting firms at the end of 2013 were McKinsey & Company, Bain & Company, Boston Consulting Group, Booz & Company, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Oliver Wyman, Deloitte Consulting, The Parthenon Group, A.T. Kearney and Accenture. With these large firms advising even larger clients on strategy and investments, it’s worth examining some of the advice and perspectives published by these agencies.

For example, McKinsey & Company, the world’s largest global management consulting firm, published a report in 2012 (Dominic Barton, “Capitalism for the Long Term,” Autumn 2012) noting that in the previous few years the world had been witnessing “a dramatic acceleration in the shifting balance of power between the developed West and the emerging East, a rise in populist politics and social stresses in a number of countries, and significant strains on global governance systems.”

For corporate executives, “the most consequential outcome of the [economic] crisis is the challenge to capitalism itself.” And while “trust in business hit historically low levels more than a decade ago,” McKinsey warned, “the crisis and the surge in public antagonism it unleashed have exacerbated the friction between business and society,” adding to anxiety over rising income inequality and other factors.

Having interviewed over 400 business and government leaders around the world, the McKinsey report noted that “despite a certain amount of frustration on each side, the two groups share the belief that capitalism has been and can continue to be the greatest engine of prosperity ever devised.” However, the report warned, “there is growing concern that if the fundamental issues revealed in the crisis remain unaddressed and the system fails again, the social contract between the capitalist system and the citizenry may truly rupture, with unpredictable but severely damaging results.” McKinsey & Company thus called for “nothing less than a shift from… quarterly capitalism to what might be referred to as long-term capitalism.”

In another instance, KPMG, one of the world’s leading accountancy firms and professional service providers, published a report in 2013 examining a list of “megatrends” in the world leading up to the year 2030 (“Future State 2030: The Global Megatrends Shaping Governments,” KPMG International, 2013). One of the major trends it referred to was “the rise of the individual,” in which technological and educational advancements “have helped empower individuals like never before, leading to increased demands for transparency and participation in government and public decision-making.”

This process is “ushering in a new era in human history,” KPMG went on. With major social issues left unresolved such as growing inequality and access to education, services, employment and healthcare, “growing individual empowerment will present numerous challenges to government structures and processes, but if harnessed, could unleash significant economic development and social advancement.”

The report further warned that there were other major consequences with the “rise of the individual,” including “rising expectations” and increased “income inequality within countries leading to potential for greater social unrest.” The fact that populations are “increasingly connected” and “faster dissemination of information through social media accelerates action” posed other concerns. John Herhalt, a former partner at KPMG, was quoted in the report as saying, “Citizens are not just demanding technologically advanced interactions with government, but also asking for a new voice.”

Further, a 2013 survey of 1,300 CEOs from 68 countries by PricewaterhouseCoopers, another of the world’s largest consulting firms, reported general views shared by CEOs around the world (“Dealing With Disruption: Adapting to Survive and Thrive,” 16th Annual Global CEO Survey). When asked about the ability of firms to deal with the potential impact of disruptive scenarios, the vast majority (75%) of CEOs responded that their companies “would be negatively affected, with major social unrest being cause for the greatest concern.” This was perceived as a greater threat than an economic slowdown in China.

CEOs, noted the report, “know they’ll have to repair the bridges of trust between business and society,” as the global financial crisis and its aftermath “have badly damaged faith in institutions of every kind.” Due to the revolution in social media, it concluded, many new “stakeholders… have an unprecedented amount of clout.”

After in-depth analyses of documents, speeches and reports from the world’s major economic institutions – from international organizations like the World Bank and IMF to global consultancy firms like McKinsey & Company and PricewaterhouseCoopers; and from big banks like HSBC, JPMorgan Chase and UBS to oligarchic platforms like the World Economic Forum – three issues are prevalent in terms of assessing the fears and threats facing the global elite: 1) growing inequality, 2) decline of public trust in institutions of all kinds, and 3) the resulting social unrest.

It should be clear by now that as global inequality continues to rise, trust in institutions will continue to fall, and social unrest will explode in new and more dramatic ways than we have witnessed thus far. We truly are entering a World of Resistance.

Read Part 1 here; Part 2 here; Part 4 here

• This article was originally posted at Occupy.com