The Mexican Revolution by Adolfo Gilly is an exhaustive analysis of the Mexican Revolution from a Marxist perspective. Gilly, himself a revolutionary, was introduced to this history while incarcerated at Mexico’s infamous Lecumberri prison in the 1960s. Friedrich Katz describes the radical milieu in the foreword:

The prisoners discussed social, political, and economic problems, lectures were given, and manuscripts were scrutinized and criticized. Octavio Paz concurred with the opinion of U.S. historian, John Womack, when he called the prison… ‘our Institute of Political Science.’

The result of these remarkable conclaves was The Mexican Revolution (2006), first published in Spanish in 1971. ((Originally entitled The Interrupted Revolution.))

And it is brilliant, absolutely brilliant.

There are many memorable passages in The Mexican Revolution, none more than its first:

Much more than any other Latin American country, Mexico won its independence from Spain through a popular war whose principal leaders… were also representatives of the Jacobin wing of the revolution… however, it was not this wing that consummated victory or began the task of organizing the newly independent country, but rather the conservative tendencies that in the course of the struggle were able to eliminate the radical wing as a result of the decline of the people’s intervention in the war.

There is more insight in this paragraph into the Mexican Revolution (or any other) than one is likely to find in a hundred books on the topic, and certainly more than one will encounter in the highly leveraged history lessons of the bourgeois schoolhouse. Here Gilly sets a sedulous tone for his thoughtful examination of the event based on the sociohistorical forces at play, and their determinant effects on the course of the war. This he does artlessly, and with laudable skill; real history, unerringly perceived and rendered. From its opening lines and throughout, this book distinguishes itself from the numbing profusion of “but-discontent-grew-among-the-(fill in the blank)-and-they-rose-in-rebellion,” narrative histories favored by bourgeois publishers. More importantly, it establishes itself as a seminal contribution to labor and revolutionary studies. One emerges from this book having learned much more than the particulars of the Mexican struggle.

The first chapter, the most important, details how capitalism developed in Mexico, and how it came into conflict with the pre-existing colonial order. And, subsequently, how the original bourgeoisie, tied as it was to the older order, gave life to a modern industrial ruling class. It is in the interplay of these tensions that the origins of the Mexican revolution are to be found.

European colonialism in the New World took different forms, depending upon what political structures the conquerors encountered. Where imperialist forms of exploitation existed, as they did in Mexico, the invaders routed the elites and assumed their position. They simply took over, and then integrated the surplus product of that exploited labor into the world economy. Gilly describes the process with his usual precision:

The Spanish Conquest… did not suppress the social relations of [the pre-existing] mode of production (most notably, tribute-based forms of extracting the surplus product). It merely levelled the empires that rode atop those relations. In Mexico and Peru… the Spaniards liquidated the dominant priestly and warrior caste and replaced it as the recipient of tribute in labor and in kind… The Conquistadores raised new temples and sanctuaries on the ruins of the old, in the manner of foreign conquerors throughout the world.

With the result that:

From colonial times… the Mexican economy may be seen as a succession of forms, changing in regard to both the system of domination and the labor-power itself, in which this massive workforce was organized by the dominant classes for the extraction of surplus product. The original… system, involving the right to demand tribute and labor from the Indians… directly articulated the Spanish Empire (and through it, the emergent capitalism of Western Europe) with the agrarian communities that had been the base and source of surplus product for the dominant castes of the [Indigenous] despotic-tributary regimes destroyed by the [Spanish] Conquest. This direct articulation, rather like a gearbox supposed to link the cogs of a huge iron wheel with a fragile wooden wheel, precipitated one of the greatest catastrophes in human history over little more than a century. About 90 percent of the pre-Conquest population was annihilated as a result of [the]… systematic destruction of the equilibrium underlying its old conditions of existence, reproduction, and interchange with nature. Its bones, muscles, nerves, brainmatter [sic], and life were almost literally transmitted into the mass of the precious metal which, passing through Spain, enormously accelerated the initial impetus with which European capitalism was entering the world.

The surviving remnants of the indigenous elites, those who capitulated, were assimilated into the new Euro-American ruling class, and the indigenous laboring classes carried on as before. As a result, the colonial order was directly dependent upon the agrarian communities to produce the foodstuffs and other basic necessities, and to provide labor in the mines. Therefore it was in the interest of the colonialists to recognize the right of indigenous groups to occupy the land upon which they lived and toiled. Deeds to these lands were sometimes issued to loyal communities, with the earliest written in Nahuatl. This legal recognition of their right to a particular tract would come to play a significant role in the revolution. Over the years many of these communities would be augmented by laborers from Europe and develop a distinct mestizo (mixed) character. Today, the majority of Mexico’s population is mestizo, descendants of the unions forged as a result of the great catastrophe.

But as Gilly describes above, many of these communities declined due to disease and other hardships, and could no longer produce the food and labor upon which their captors depended. This necessitated the importation of the Spanish hacienda system of production based on private property. While itself a feudal institution, at least in its initial phase in Mexico, the haciendas introduced peonage, and capitalism in the form of wage-labor to Mexico, and would become the focus of the peasant rage which would propel the revolution:

Together with his… administrators, the… ‘hacendado’ personified the power of the dominant classes. The hacienda had a prison, a church, and a priest, distributing rewards and punishments for this world and the next… This function then passed, suitably transformed, from the colonial to the Porfirian hacienda, so that the institution came to stand as the material form of the peasants’ oppression and the principal object upon which their revolutionary fury would be vented…

Predictably, these hacendados became acquisitive, and frequently mounted attacks on independent agricultural villages and their communal lands, called ejidos, which they coveted. With the tacit approval of corrupt state officials, and by all manner of coercion up to and including violence, the hacendados seized these tracts, very often with the result that their previous inhabitants had little choice but to become laborers for the very people who confiscated their lands and destroyed their livelihoods. Thefts like these did nothing but stoke the flames of the inferno spreading below.

This process was accelerated by what is known in Mexican history as La Reforma. Its causes and principals need not concern us here, but its effects are crucial to a proper understanding of the conflict that was to come as they heralded the age of Mexican enclosure. Its upheavals and accommodations, fusions and dissolutions, were nursery to the property relationships and production methods which resulted in new class formations. These social fault lines in turn became the battle lines of the revolution.

This process was accelerated by what is known in Mexican history as La Reforma. Its causes and principals need not concern us here, but its effects are crucial to a proper understanding of the conflict that was to come as they heralded the age of Mexican enclosure. Its upheavals and accommodations, fusions and dissolutions, were nursery to the property relationships and production methods which resulted in new class formations. These social fault lines in turn became the battle lines of the revolution.

In essence, La Reforma was a bourgeois revolution. Its aims were liberal in both modern and classical sense in that it sought to diminish the power of the church and military, two institutions whose privilege descended directly from the old Spanish order; and to bring them under the authority of the popular (i.e. electoral) government. The church was compelled by Reform law to sell off large segments of their land in small lots and at low prices. The goal was to break the power of the church and hacendados by moving from the concentrated agricultural production of the hacienda system, to the diffuse, small-scale output of yeoman producers, whose farms would exist alongside the ejidos. Should this Jeffersonian approach succeed, not only wealth but political power would be redistributed, or so it was hoped.

Where the church refused, its holdings were confiscated and broken up into smaller pieces and thrown onto the market.

While no doubt most of the Reform leaders had noble intentions (as is evidenced by many of their initiatives not mentioned here), the effect of these land enclosures was not the rise of of a new system of agricultural production based on independent smallholders, but rather the extension of the wealth and power of the hacendados. For it was they who had the money who could buy up these new plots and monopolize agriculture. And the more powerful they became, the more aggressive they were in stealing the ejidos of the independent villages.

The result of the Reform was twofold: It did indeed clear the path for capitalism by exposing a much larger part of Mexico’s land and burgeoning industrial capacity to the hegemony of capital, but it also was a boon for the hacendados, who as a result constituted an agrarian oligopoly.

Thus as industry grew as a result of the reforms, and as foreign capital flooded the country, these forces merged with the hacendado power, and the two became interdependent. The Mexican ruling class developed a hybrid character: part feudal, part bourgeois. This odd duality served the ruling class well in its war against its laboring classes, but at the same time the tensions between these two wings would cause schisms, and these ruptures would manifest themselves in the course of the war. The most tangible result was that the head of state favored by one wing would all too often end up assassinated by the other.

One of the Juaristas, as the reformists were called, Porfirio Diaz, soon rose to power. During his 36-year tenure, known as the Porfiriato, the Mexican economy would expand at a frantic pace. The laying of endless kilometers of railway, and capital-friendly economic policy, triggered the kind of growth that few nations have ever experienced. The rich got richer, but the poor slid deeper into privation. The hacendados, with nothing to fear so long as their great sponsor was in power, grabbed more and more communal land. Very often this was done with nothing more in mind than to dispossess the peasants so as to force them into wage-labor to sate the ever growing demand for labor. Thus in the Porfiriato, Mexico’s peasants underwent the same process that had begun in England centuries before, and with the same immiserating effect.

Gilly:

These [new industries] were part of the preparatory formations of a new proletarian class out of peasant and artisan layers. The real impetus came with… large-scale industry… and the generalization of wage labor as the sole means of subsistence for a class of workers owning nothing but their labor-power… [so that] wage labor [became] the structurally, if not numerically, dominant position in the whole system of work relations.

Gilly goes on to describe the nascent Mexican proletariat’s uniquely colonial character:

From its origin in the [Spanish] Conquest… The bottomless pool of rural labor led, on the one hand, to a constant squandering of manpower and a depreciation of human life which… spawned a distinctly Indo-Spanish ideology of death, recycled by capitalism to normalize the staggering disregard for safety at work; and on the other hand to a swollen reserve army [of labor] and a constant downward pressure on wages…

But even as La Reforma spawned the Porfiriato, the latter, by force of its own inertia, dashed the very hopes which gave rise to the reforms. With the complete control of Mexico in Diaz’ hands, the promise of free markets and upward mobility went unfulfilled. Wealth and power was compressed into the top layer of the bourgeoisie and its administrative arm, the Diaz regime.

Gilly:

Now, the liquidation of free villages served not only an economic but also a political purpose. Whereas the Spanish Crown had co-existed with such rural, tributary communities, even defending some of their prerogatives against hacienda encirclement, the modern capitalist organization… were hostile to any element of autonomous organization, any relation unmediated by capital… [thus] without any conscious design or expectation, village resistance increasingly converged with other forms of peasant and working-class struggles… The urban petty bourgeoisie, too, swollen by the development of capitalism, was breaking from its former silence and attraction to Porfirian ‘peace and progress.’By the turn of the century, the political ossification of the regime had so foreclosed upward social mobility that the petty bourgeoisie was driven into attitudes of discontent or even rebellion. This… served… to produce symptoms of crisis and division among the capitalist and landholding bourgeoisie in whose name… Diaz… exercised power.

Thus the discontent swelling up from below was met by those growing layers of the bourgeoisie shunned by the Porfiriato. Finally, Francisco Madero, wrote a book denouncing Diaz, and launched a campaign for the presidency in 1910.

Madero was representative of the bourgeois opposition to Diaz. He was a hacendado, but he also owned a smelting business which was doing quite well as a result of the industrial growth cultivated by the regime. However, Diaz granted a monopoly to an American company whose owner was a long-time stake-holder in the Porfiriato. Madero had to shutter his business.

Madero’s book caught on and the anti-reelection campaign grew swiftly. Diaz jailed him, and Madero was forced to run for office from his cell. After yet another corrupt election, Diaz was proclaimed the winner by a garishly wide margin. Madero escaped with the help of sympathizers, a civil war ensued, he won, and Diaz left Mexico for Europe never to return. Madero assumed power.

Before his triumph, Madero produced his Plan de San Luis Potosi which he had written while in custody in that city. In it he promised restitution of village lands, and the freeing of political prisoners.

Madero, however, was unable to suppress the rebellion he had summoned. The peasants had played a leading role in the army which had defeated Diaz, they were now refusing to disarm and pressing their demands with a militancy which terrified the ruling class. Madero instituted some reforms, but they fell short of expectations. One of the first of his supporters to turn against him was Emiliano Zapata of Morelos, who produced his Plan de Ayala as a response to Madero’s failure to deliver upon his promises.

Madero, however, was unable to suppress the rebellion he had summoned. The peasants had played a leading role in the army which had defeated Diaz, they were now refusing to disarm and pressing their demands with a militancy which terrified the ruling class. Madero instituted some reforms, but they fell short of expectations. One of the first of his supporters to turn against him was Emiliano Zapata of Morelos, who produced his Plan de Ayala as a response to Madero’s failure to deliver upon his promises.

There would be many “Plans” before the war was over, but Zapata’s was the most radical and far-reaching, and he became the focus of peasant aspirations, at least in the south. While all the plans called for some measure of agrarian reform, most called for peasants to present their deeds (those that had them, that is) to courts once the revolution was over. Zapata, on the other hand, urged all peasants to seize their lands immediately, and hold on to them with “guns in hand.” He was also calling for the confiscation and nationalization of the private property of all those who opposed the revolution.

As stated earlier, Gilly is an orthodox Marxist, and one of the themes to which he returns time and again in this book is the inability of peasants to formulate a truly revolutionary socialist program.

As he succinctly put it: “The exercise of power demands a program. The application of a program requires a policy. A policy means a party. The peasants did not have, could not have had, any of these things.”

As commendable as Zapata and his plan were, it still did not call for the abolition of capitalism, merely for protections for peasants and workers and severe punishments for law-breaking capitalists; it left the existing social order in tact. Indeed, Zapata would come to specifically reject altering the Plan de Ayala along socialist lines, as we shall see.

With Madero faltering, Mexican capital conspired with the U.S. government to eliminate him. He was overthrown and subsequently murdered by General Victoriano Huerta.

Claiming that he feared a restoration of the Porfiriato and wanted to save the revolution, Venustiano Carranza, or “Don Venus” as one of his subordinates, Pancho Villa, called him, led an army against Huerta. He had the support of the United States as Huerta too had failed to put down the rebels, and had become close to the Kaiser. The U.S. Army occupied Vera Cruz, the port through which Huerta was receiving his supplies from Germany. Cut off from his European benefactors, Huerta was isolated and left the country.

Don Venus, also a hacendado, gained power, but then like Madero he declared that the revolution was over and ordered the peasants to disarm. Two peasant leaders, Pancho Villa from the north, and Emiliano Zapata from the south, refused saying they would never disband until the land reform and other measures were carried out. War ensued, and Carranza fled to Vera Cruz when the armies of Villa and Zapata converged on Mexico City. These two factions would fight it out with Carranza eventually winning, thereby again earning the support of the United States. The Villistas were reduced to a guerrilla force, with Zapata hanging on in his Morelos stronghold for years.

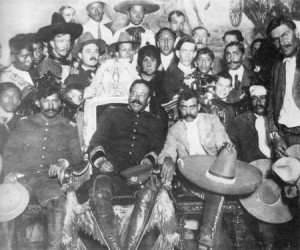

“Villa en la Silla.” Villa in the presidential chair after routing Carranza. Zapata is immediately to his left with the enormous sombrero.

Gilly describes a few poignant scenes in which the victorious peasants reflexively acted in a deferential, even servile, manner to their bourgeois allies, those who would be standing before Diaz’ firing squads if not for the ingenuity and daring of the peasant leaders. Yet the latter instinctively subordinated themselves to these men of “culture,” the same men who would soon betray them.

Gilly reproduces the heartbreaking conversation at Xochimilco:

Viila: I don’t want to take public positions, because I don’t know how to deal with them. We’ll see what these people are up to doing. we’ll just appoint the ones who aren’t going to make trouble.

Zapata: I’ll advise all our friends to be very careful-otherwise they’ll get the chop… Because i don’t think we will be fooled. It’s been enough for us to rein them in, keeping a very close watch on them, and to keep feeding them under our control.

V: It’s very clear to me that we ignorant men make the war, and the cultured people have to make use of it. But they should not give us any trouble.

Z: The men who’ve worked the most have the least chance to enjoy these city sidewalks. Nothing but sidewalks. As for me, each time I walk down over these sidewalks, I feel as though I am tumbling down.

V: This ranch is too big for us; it’s better out there. As soon as this business is sorted out, I’ll be off north to the country. I’ve got a lot to do up there. And the people there will fight hard.

Gilly analyzes the exchange and relates it to another of the his major themes–centralization:

This dialogue contains the seeds of… political and military defeat. Unable to keep power in their hands, the two leaders are prepared to hand it over. They therefore give up the idea of a centralized army, which would require a centralized state power, and decide to forsake the center that is already in their hands: each will return to fight in his own region, whose horizon they have not been able to transcend in a vision of the nation…

Whether one favors the centralization of revolutionary state power, or believes that the social revolution is best served by a federation of autonomous peasant and proletarian organizations, Villa and Zapata created neither. They failed utterly. They deposed one state, and then created a new one and entrusted its care to their class enemies. It was the beginning of the end. Gilly:

[The peasants] could not see a political way forward once the gigantic social upsurge had reached its peak. This in turn reacted upon the upsurge itself, starting to break up the perspective which had momentarily seemed to offer itself through the alliance with the petty bourgeoisie… Thus, the immediate dispersion of military forces had deep social roots: it expressed the historical impossibility of a national peasant government and foreshadowed the slide into a form of large-scale guerrilla warfare conducted by retreating peasant guerrillas. In other words, it announced that the revolution had reached the highest point attainable under the existing leadership…

Once Carranza had publicly broken with Villa, he could no longer pose as the standard bearer of the revolution, so he feinted to the Left. His Plan de Guadalupe had offered little to the peasants (and privately he criticized Madero’s Plan de San Luis Potosi for its meager agrarian reforms saying that it created “unrealistic expectations” among the peasantry), but now he endeavored to win peasant favor with a new plan which promised grants of public lands. Now in power, he did initiate the process, and it did win him some support.

In addition, Carranza appealed directly to the urban proletariat. The largest worker organization then in existence was the Casa del Obrero Mundial in Mexico City. (It translates roughly as International Workers’ House.) In the COM were a great many anarcho-syndicalists (perhaps a majority, although this is disputed) and a smaller number of Marxists. Organized labor had been violently suppressed during the Porfiriato, when Madero took over the COM was formed (or surfaced, some say it had already existed as an underground organization) and it began to agitate. Carranza now offered the eight-hour day, the right of workers to organize and other enticements.

This caused a split. A large minority, mostly anarchists, opposed the cross-class agreement arguing that they cannot ally with the bourgeoisie, nor should they be making deals with the state. Carranza, they pointed out, was a capitalist; an adversary, not a partner. The other faction felt that the right to legally organize was too important to squander, and that through that activity they could hasten the revolution more effectively than by fighting Carranza in the short term. (Or at least that is the rationale they advanced in defense of this squalid deal.) The latter group, being a majority, won the vote and threw their support to Carranza. They even formed “Red Battalions” and fought alongside Carranza’s army against Villa and Zapata.

It wouldn’t be long before Carranza would renege on his promises, and crush the COM and subsume the Red Battalions into the regular army.

The losing faction in the COM dispute could not abide a pact with Carranza and bolted. A great many of them went to nearby Morelos and joined the Zapatistas. Their ideas, along with those of the anarchist Magonistas, would influence the Morelos Commune.

Carranza thus won enough support nationwide, for as long as he needed it, from the workers and peasants, that he was able to wrest control of Morelos from Zapata, eventually luring its leader into a deathtrap. Carranza wouldn’t have long to celebrate though, as he in turn was assassinated on the orders of his chief ally in the defeat of Villa, Alvaro Obregon, who succeeded him.

Obregon brought stability by coming to an understanding with Villa, who in exchange for some concessions, retired to live quietly on a hacienda run collectively by him and some of his men. (That is until Obregon would have him killed in 1923.)

With the last remaining armed threat thus pacified, Obregon consolidated the gains of the counterrevolution in the time-honored manner–the patronage system. Gilly:

This system played an indispensable role by making the trade-union bureaucracy a partner in the use of the state apparatus for private gain. Together with the firing squad and the assassin’s pistol, it also served to maintain control over the military factions, which, given the preponderant role of the army in establishing and maintaining the regime, were constantly incited to fresh conspiracies. Obregon… summed it up well: ‘No general can withstand a 50,000-peso cannon-shot.’Obregon created the model to which subsequent governments have clung. The old principle of transformation of power into property became the golden rule of the Mexican postrevolutionary political regime.

It is at this point that the book ends. Gilly sums up the gains made by the revolution:

The whole curve embraces a period of ten years. During that time, the peasant masses–that is, the people of Mexico, 85 percent of whom lived in the countryside in 1910–underwent the most dramatic experiences: they took up arms, forced their way into a history that had previously unfolded above their heads, marched across the country in every direction, shattered the army of their oppressors at Zacatecas, occupied the national capital, raised Villa and Zapata (two peasants like themselves) to the summit of the insurrection, issued a series of laws, and embarked on a systemic attempt at self-government in the South, creating elementary decision-making bodies and a new juridical structure. In other words, they ‘rose independently and placed on the entire course of the revolution the impress of their own demands, their attempts to build in their own way a new society in the place of the old society that was being destroyed.’ In their last momentous experience, the painful ebb of the revolution, they and their leaders continued to fight in defense of the position already won… Even after they had lost their leader and suffered defeat in the South, they made a last great effort to tip the scales in the victorious faction against Carranza’s right-wing policies… All this did not, of course, amount to a socialist revolution, but neither was it merely a bourgeois revolution. It is true that every bourgeois revolution has a left wing that breaks its bounds at the climactic moment and is then smashed by its victorious center.In Mexico, however, this wing not only embodied the continuity of the whole revolutionary cycle, but… evolved a form of popular power that has been ignored in official histories…

Appropriately, Gilly spends a lot of time on the Zapatistas and the Morelos Commune, devoting a whole chapter to it. It is the high-water mark of revolutionary progress, and the most lasting influence of the war. Next to perhaps Che Guavara, Emiliano Zapata is the most beloved revolutionary figure in the history of Latin America, and the movement he created continues to be an inspiration to activists and oppressed people the world over.

The Commune lasted ten years, which gave it time to develop further than its only predecessor, the Paris Commune of 1871. The Morelian Communards crafted their own system of self-governance, even producing their own currency. And, of course, it redistributed hacienda lands to the peasants. But like its Parisian counterpart, it was born on a battlefield and surrounded by superior forces which would drown it too in blood. Between 1910 and 1920, the years of the Commune, the population of Morelos would be cut in half. Nevertheless, it flourished for a time, and was a marvel to an American visitor:

Here, unlike Mexico City, there was no busy display of confiscated luxury, no gleeful consumption of captured treasure, no swarm of bureaucrats leaping from telephone to limousine, only the regular measured round of native business. The days Zapata passed in his offices in an old rice mill at the northern end of [Tlaltizapan], hearing petitions…deciding strategy and policy, dispatching orders. In the evenings he and his aides relaxed in the plaza, drinking, arguing about plucky cocks and fast and frisky horses, discussing the rains and prices with farmers who joined them for a beer, Zapata as always smoking slowly on a cigar. ((This is from John Womack’s Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, which Gilly reproduces.))

The details of its self-administration need not concern us here, save to note that it stopped short of establishing socialism, as the passage above indicates. It was, in the end, a reformist state, one which blunted the sharp edges of capitalism, but failed to eliminate it altogether. Zapata’s own feelings about socialist ideas were somewhat ambivalent. Gilly describes a scene where aides bring books on socialism to Zapata and ask him to read them. There were two eyewitness accounts to a subsequent discussion of the topic which, in essence, agree. Paraphrasing:

The details of its self-administration need not concern us here, save to note that it stopped short of establishing socialism, as the passage above indicates. It was, in the end, a reformist state, one which blunted the sharp edges of capitalism, but failed to eliminate it altogether. Zapata’s own feelings about socialist ideas were somewhat ambivalent. Gilly describes a scene where aides bring books on socialism to Zapata and ask him to read them. There were two eyewitness accounts to a subsequent discussion of the topic which, in essence, agree. Paraphrasing:

Z: I have read the books you gave me, and I find nothing in them which is objectionable. These are noble ideas, but it would take generations to implement such ideas. And that being the case I am not willing to alter the Plan de Ayala along these lines.

As it would happen, it would not matter one way or the other as the Morelos Commune was running out of time. Carranza’s Leftward lurch won him enough support that he was able to isolate Villa in the north and the Zapatistas in Morelos. The cordon was tightening around them and as it did Carranza initiated an offensive against Morelos under the ruthless general, Pablo Gonzalez. He also issued an amnesty for defectors. The effect of Gonzalez’ genocidal campaign and the resultant demoralization led a number of Zapatistas to surrender and accept the amnesty. This in turn led Zapata to move to the Right in order to gain whatever allies he could as the situation grew more dire. It was in just such an effort that Zapata was ambushed. His death marked the end of the Commune, and, one might say, the revolution itself.

The Mexican Revolution is a masterpiece, but there is room for criticism.

The Mexican Revolution is a masterpiece, but there is room for criticism.

This book requires some knowledge of social theory, it is not for beginners. If one is not familiar with the basic theories and nomenclature of class analysis then much of what is best in this work will be unintelligible. As important as this work is, it is a shame that it couldn’t be a little more accessible.

In terms of describing the course of events and the socioeconomic forces which shaped them, and then relating that analysis in a cogent manner, it simply does not get any better than this book. However, there is room for comradely debate about some of his interpretations and conclusions.

I believe Gilly underestimates the role of the United States in the Mexican Revolution. Generally he depicts the U.S. government as confused by the flow of events and guarded in its reaction. He also presents the relationship between Carranza and the budding empire on his border as hostile, and American recognition of Carranza’s regime reluctant. Whereas the evidence suggests that he was Washington’s man from the beginning, and that America’s interest in the Mexican Revolution was considerably more wide-ranging and strategic. That is to say that U.S. capital was more concerned with the threat of revolution than they were with the potential loss of this or that lucrative concession.

The U.S. invaded twice. The occupation of Vera Cruz finished Huerta and brought Carranza to power. The Punitive Expedition against Villa was contemporaneous with Pablo Gonzalez’ assault on the Morelos Commune. Is it a coincidence that while Carranza was mounting a final offensive against the greatest threat to his power the U.S. Army was holding down the only man who could possibly come to Zapata’s aid? This invasion is invariably judged a failure given that it did not succeed in capturing Villa. I think it a success as it achieved its mission: allow Gonzalez a free hand to crush the Morelos Commune. The Expedition gave up its pursuit of Villa once Gonzalez had seized control of much of Morelos and chased Zapata into the hills. If the real purpose was the stated one–get Villa and bring him to justice for his assault on Columbus, New Mexico–then they would never have called off the mission. Or, if one believes that the Expedition was recalled because it was decided that the war in Europe was of greater import, then at the very least they would have demanded the Mexican government capture Villa and hand him over. As it was they just seemingly lost interest in him.Carranza barked and brayed against the invasion, which Gilly takes as sincere. I doubt it. There was even a clash with Carranza’s forces, but this wouldn’t be the first time in the history of warfare that a skirmish was staged for propaganda purposes, nor the last.

We also know that American intelligence agents were monitoring and had infiltrated Mexican revolutionary groups inside the U.S. They were instrumental in sabotaging the Magonista Revolt. (More on it later.)

Indeed, one has to wonder if the U.S. delayed its entry into WW1 as long as it did for fear that the conflagration to the south might cross its border. Pershing’s Punitive Expedition crossed back into the United States in February of 1917. Two months later he was in Europe.

Obregon did not gain recognition from the United States until July 23, 1923, three days after Pancho Villa was assassinated. Another coincidence? Gilly lets this synchronicity pass without comment.

If it is true that the United States murdered Ricardo Flores Magon, provided rearguard support for the destruction of the Morelos Commune, and insisted upon the elimination of Pancho Villa as a prerequisite for normal diplomatic relations, then it must be said that it was a major factor in the revolution. More, I think, than Gilly will attest.

But the largest flaw in this book is the extent to which Gilly underestimates the theoretical and material contributions made to the revolution by the anarchist Magonistas, particularly its eponym, Ricardo Flores Magon, and his brothers Jesus and Enrique. But this brings us to the great cleft within the socialist tradition between the libertarian wing, ranging from anarchism to Left communism and even to Left Marxism on the one hand, to the authoritarian Marxist/Blanquiist wing on the other. Gilly is a Leninist, and he thinks like one. In the main this has served him well in his analysis of the revolution, and in formulating the book. But for Marxists history is a science, and Marxism is the study of that science and the practical application of the knowledge derived therefrom. And there sometimes follows from this a kind of ideological xenophobia toward exogenous social theory or movements.

Gilly exhibits symptoms of this disease. For instance, in line with Marxist belief in the unique revolutionary role of the working class, Gilly, echoing Trotsky, repeatedly insists that peasants cannot come to a truly revolutionary socialist consciousness, cannot form a revolutionary party, nor can they conduct a truly socialist revolution. This is remarkable in that at the very same time as the events he chronicles in his book, the SRs (Party of the Socialist Revolutionaries) in Russia are doing precisely that. Moreover, It seems obvious that the peasantry can indeed effect a successful socialist revolution as largely agrarian countries (the kind Marxists call “backwards”) are the only places where such events have ever occurred. The proletariat has thus far not managed a single successful revolution, the peasantry has scored a handful.

The other major line of criticism which Gilly pursues is the failure of the peasant leaders to form a centralized revolutionary structure to coordinate their activities.

Two objections:

1) A lack of centralization (by which Gilly means a hierarchical command center: bosses making decisions and giving orders, and subalterns complying under pain of penalty) did not keep Villa and Zapata and “the peasant masses” from undergoing “the most dramatic experiences: they took up arms, forced their way into history… marched across the country in every direction, shattered the army of their oppressors… and embarked on a systemic attempt at self-government in the South, creating elementary decision-making bodies and a new juridical structure…”

2) They did form a central national command center. They called it the Convention, the one they handed over to the “cultured” men, who certainly did have a “vision of the nation.” It was the fatal mistake which undermined the revolution (not that they were likely to succeed no matter what they did) as it was the organ through which the bourgeoisie clambered back to power, before it in turn was overtaken by Carranza’s even more reactionary forces.

Undercentralized or overcentralized? Whose vision do these events affirm, Marx or Bakunin? Zapata’s Southern Liberation Army was thoroughly decentralized, with its many autonomous units acting independently, coordinating their activities when advantageous. And they “forced their way into history…shattered the army of their oppressors,” and, astonishingly, lasted a full decade despite impossible circumstances.

Here Gilly’s assertion about the peasantry not being able to come to revolutionary class consciousness may have some merit, as Villa and Zapata failed to, but his contention that the revolution collapsed because of lack of centralization seems rooted more in Marxist theory than in fact.

For Marxists revolution is a science, and as such it requires proper theory and a program to conquer state power. Once attained, a centralized workers’ state is necessary, so their teleology goes, to implement socialism and to hold its enemies, Left and Right, in subjection. Marx and Engels said so, and Lenin and Mao did just that. But for those of us farther Left, who see socialism not so much as a prescription as a catharsis; who see socialism as the liberation of the eternal prisoner, who, once unchained, needs less an administrative plan or guiding principle than an unobstructed path; for us the workers’ state is at best a prophylactic, and at worst the organizational locus of reaction. This occurred in communist Russia and China with catastrophic results, and was transpiring in the Convention until its descent into counterrevolution was preempted by its demise.

In the end, Zapata and Villa were Juaristas, reformers, lacking in socialist class consciousness, and the Convention was bound to fail. But what if it were a Bolshevik-style government, would it have fared any better? Ignoring all other factors for the moment, can socialism be dispensed? If socialism demands revolutionary socialist class consciousness, as Gilly agrees that it does, can it be gained from taking orders from above? Meeting production quotas? As Rosa Luxemburg stated in her “The Russian Revolution,” socialism cannot be imposed by ukase from above. If socialist consciousness must exist at the level of production and distribution for socialism to occur, what is the need for, or advantage of, a layer of coercive, discretionary power above that level, particularly when weighed against the grave, counterrevolutionary danger it poses? Socialism is a thing done by the laboring classes, not for them, and certainly not to them. Was the vesting of sovereign decision-making power in the peasants of Morelos, of which Gilly writes enthusiastically, an aid or impediment toward the development of socialism? He can’t have it both ways. He writes admiringly of the self-governance of the Morelos Commune, and in the next moment says the revolution was doomed due to the absence of a centralized national state. But such a state would have superseded the Commune and annulled those democratic structures which Gilly admires. No society can long exist with decision-making authority flowing both bottom-up and top-down. In the end one current has to surrender to the other.

The Bolsheviks faced this dilemma early on when the Vesenka began issuing orders to factories in the provinces. ((The Vesenka was the Bolshevik’s Supreme Economic Council.)) Confusion followed and these workers responded that they were under the jurisdiction of their local soviets, and it was those bodies to whom they were responsible. Lenin settled the dispute with the concept of “dual subordination,” insisting that workers follow orders from both entities. It was an artful dodge as it sidestepped the issue of who was sovereign, but, predictably, conflicting directives were eventually given. Cagey as ever, Lenin then suggested that workers could disobey orders from the Vesenka, but only if they did not come directly from the commissar of the particular industry in question, in which case those orders must be carried out. This rendered impotent the local soviets, then still electoral bodies under workers’ control, and reduced the proletariat to servitude once again. When workers rioted, Lenin reacted in his customary manner–he denounced the rebels as counterrevolutionaries in league with White forces, and sent in the Cheka.

It is difficult to imagine that Gilly’s centralized Mexican state would have reacted differently to challenges from below.

On the one hand we have Blanqui’s authoritarian conception that capitalism holds workers and peasants in such a brutish state of ignorance and debilitation that they can never develop socialist class consciousness on their own, nor are they competent to run a modern industrial society by themselves should they be freed, hence it is necessary that a small, enlightened elite make revolution and direct the affairs of state for an unspecified period thereafter; on the other hand we have in the libertarian model the belief that socialism can only be achieved by the direct assumption of political power, to the necessary exclusion of any other power, by the laboring masses themselves; Gilly seems to have a foot in both camps, here endorsing one, there demanding the other. It is unfair to expect the author to remedy this historied conflict, but it is of analytical value to note that there is an unresolved conflict in his approach.

This contradiction manifests itself in The Mexican Revolution most conspicuously in the person of Ricardo Flores Magon.

In a footnote Gilly states that Magon’s ideas didn’t catch on, which is an extraordinary thing for a Marxist to say as it was only the Magonistas among the revolutionary factions who articulated an unequivocally revolutionary socialist view (in this case a Libertarian one). It was not Magon who penned homages to entrepreneurs or advocated ceding political control to men of “culture.” Yet his name barely appears in The Mexican Revolution.

Ricardo Flores Magon is an extraordinary figure. He and his associates organized the Cananea and Rio Blanco workers’ strikes in 1906 and ’07, which many historians cite as the trigger for the revolution. If so, then the Magonistas launched the Mexican Revolution.He and his brothers published a newspaper, Regeneracion, which was relentless in its criticism of the Porfiriato, making the brothers wanted men. They hid out in the hills or empty boxcars or the cemetery, and then they would suddenly appear, set up slapdash, and quickly begin to harangue against Diaz and for anarchism. They and their ideas were so popular with Mexicans that the Rurales (Diaz’ goons) were never able to apprehend them as the brothers would invariably receive warning of their approach. They became such a nuisance for Diaz that he stepped up efforts to capture the elusive rebels, and eventually they had to cross the border.

Once in the U.S., they continued to publish their paper, smuggling issues into Mexico. Magon also became acquainted with the IWW and began to work with them. He proved to be an effective recruiter, successfully organizing workers of all races.

From his offices in Los Angeles, the Magonistas planned an uprising in Mexico for January, 1911. Armed clashes occurred in many Mexican cities (six to fourteen, depending on whom you read), and they managed to hold Tijuana for six months. There they declared the Republica Socialista de Baja California, the first socialist republic in history. A sordid disinformation campaign was directed against it from Washington and Mexico City, and it was eventually toppled through the combined efforts of soldiers and saboteurs.

Ricardo was arrested many times by U.S. authorities. Caught up in the dragnet of Palmer’s raids, he was sentenced to twenty years for obstructing the war effort in 1918. He was suicided in his cell at Leavenworth in 1922.

From a military point of view, Magon was not as important a revolutionary leader as Zapata or Villa, but in all other respects he was. As an indication of how influential he was, Madero, when he had first defeated Diaz at Ciudad Juarez, declared that he was the “provisional” president and that Ricardo Flores Magon was the provisional vice president. He was able to make this absurd claim because he knew that his “vice president” was in an American prison and unable to refute it. That Madero invoked the name of Flores Magon to gain support for his accession to power suggests rather forcefully just how popular the anarchist rebel was with the laboring masses.

Many Magonistas found their way to Morelos and became important advisers and strategists. As Gilly concedes, and Zapata affirmed, the Magonistas were the greatest ideological influence on the Zapatista movement. The Morelos Commune moved steadily to the Left (at least until the very end) because it was driven there by the Magonistas and the COM defectors. The current Zapatista movement, admired the world over, is both legatee and incubator of that tradition.

Magon’s ideas didn’t catch on?

Lessons of the Mexican Revolution? The most important is the one gleaned from all revolutions: Beware of cross-class alliances. Magon, employing Flora Tristan’s oft-cited adage (invariably misattributed to Karl Marx), stated it plainly:

Governments have to protect the right of property before all other rights. Do not expect then, that Madero will attack [that right] in favor of the proletariat. Open your eyes! Remember a phrase, simple and true, and as truth indestructible: The emancipation of the working class must be the work of the workers themselves. ((Regeneración, December 10, 1910.))

Left-sectarian squabbles aside, The Mexican Revolution is a tremendous contribution to our discourse. I do not know where to begin or end in praising this book. It is a tour de force of history written by a strikingly lucid and perspicacious observer, one whose literary skills are only surpassed by his political acumen. This book is historiography at its very best, a must-read for all revolutionologists. If little green men ever do land in my backyard, this book is what I will offer them.

Somebody once famously said of Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution that it was “the best account ever written of, well, anything.” I believe that distinction belongs to Adolfo Gilly.