I’ll never forget the day my dad came back from Vietnam. It was in February 1970. I was fourteen and opposed to the war. My mom, some neighbors and us kids had made a banner saying Welcome Home. We drove to BWI airport near Baltimore, unloaded the banner and some balloons and headed to the terminal gate. The actual moment I saw him was somewhat surreal. He didn’t look much different, but he certainly seemed different. After hugs and handshakes (hugs for the girls and handshakes for us boys), our family headed to the parking lot and the drive back home. The first couple of days were uneventful in terms of my dad being back in the house. Within a week, however, a certain tension became apparent as my father attempted to assert his previous authority over the household–an authority that in his mind was not tempered by his tour in Vietnam. However, it had been. It was apparent to us kids in his sometimes irrational lashing out for seemingly petty reasons. I can only imagine what my mother was going through. We were among the lucky ones. His family and makeup prevented him from going over the edge like many of his fellow returnees. Within a year or so he had put whatever demons the war had unleashed back wherever one puts such demons and was more or less the same man he was before his tour in Vietnam had begun.

A buddy of mine we called R, spent a year in the Navy off the coast of Vietnam begrudgingly helping the US launch jet planes to strafe the people and countryside of Vietnam. He joined the Vietnam Veterans Against the War as soon as he got his discharge papers. He and I spent many an hour talking politics, books, and women over the years. One conversation occurred when we were somewhere in California’s Central Valley on Veterans’ Day. As we sat in the shade of some trees in Salinas and sipped surreptitiously on a quart of Rainier Ale, R began talking about friends of his from his Navy days. After all, noted R bitterly, this is our day. He continued by noting how much better vets were treated after they were dead. Shit, he said, you even get a decent burial. And a freakin’ American flag to go with it. When you’re in their goddam uniform, you ain’t no better than a maltreated dog who they’re trying to kill. If you get out alive, they just want you to go away. Especially if you have an ailment that can be attributed to their war. R eventually married and helped raise two children. When he was around fifty he was diagnosed with a disease related to the war that was exacerbated by his reckless lifestyle in the years immediately following his discharge. He met an untimely death a few years ago while waiting for a transplant. He did get a decent burial. And a freakin’ flag.

There are many more men and women who were in the military with their own stories. Some have better endings than others. No one makes it through unscathed. Some just hide their scars better. That’s what a friend who did veterans counseling before he died told me. Washington’s latest wars have produced a new crop of these men and women. Although the wars may be different, the wounds are equally painful.

Often left unsaid when the media writes about returning veterans and their trouble adjusting to civilian life is how a veteran’s loved ones are affected. If one wishes to maintain the vocabulary of modern war, then the appropriate label for the lovers, partners, parents and children of the returning soldier would be collateral damage. Think of a cluster bomb. If the returning veteran is a casualty of the explosions that occur on original impact, then the veterans’ families and loved ones would be those who are the casualties that occur from the bomblets that detonate later. Of course, this scenario of injury and death is also replicated among those whom the imperial army has attacked many more times over.

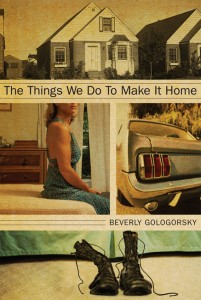

Author and antiwar organizer Beverly Gologorsky wrote a book a couple years ago titled Things We Do To Make It Home. This book was recently released in paperback by Seven Stories Press. It is a beautifully wrought story of a group of Vietnam veterans, their lovers, families and friends set in the 1990s. Twenty years after their return from the jungles of Nam the world they live in is still littered with the veterans’ experience in combat. Like so many of their real-life comrades, the men in the story have left much damage in their wake. Simultaneously, there is a love that binds them all together. That same love reaches across the lines between suburb and city while it tears relationships into remnants barely held together by threads of memory. There is no blame here, despite the desire to find somewhere to place the despair and anger resulting from the demons that define the lives these men have lived. The women who have loved them despite their better sense, the hopelessness the men hide with drugs and alcohol and the children who wonder where there father really is even when he’s sitting in the same room are portrayed with an emotional and spiritual depth the reader won’t find in newspaper reports about veteran suicides and PTSD statistics. There isn’t a lot of hope in this novel, despite the optimism voiced by some of its characters. These are men who know they were screwed and can’t seem to figure out how to get past the war they were sent to fight. Nonetheless, they go on living life as best as they can while often unaware of the pain they cause–a pain directly related to the guilt they feel because of the injury they caused to those their commanders called the enemy while fighting Washington’s war.

Author and antiwar organizer Beverly Gologorsky wrote a book a couple years ago titled Things We Do To Make It Home. This book was recently released in paperback by Seven Stories Press. It is a beautifully wrought story of a group of Vietnam veterans, their lovers, families and friends set in the 1990s. Twenty years after their return from the jungles of Nam the world they live in is still littered with the veterans’ experience in combat. Like so many of their real-life comrades, the men in the story have left much damage in their wake. Simultaneously, there is a love that binds them all together. That same love reaches across the lines between suburb and city while it tears relationships into remnants barely held together by threads of memory. There is no blame here, despite the desire to find somewhere to place the despair and anger resulting from the demons that define the lives these men have lived. The women who have loved them despite their better sense, the hopelessness the men hide with drugs and alcohol and the children who wonder where there father really is even when he’s sitting in the same room are portrayed with an emotional and spiritual depth the reader won’t find in newspaper reports about veteran suicides and PTSD statistics. There isn’t a lot of hope in this novel, despite the optimism voiced by some of its characters. These are men who know they were screwed and can’t seem to figure out how to get past the war they were sent to fight. Nonetheless, they go on living life as best as they can while often unaware of the pain they cause–a pain directly related to the guilt they feel because of the injury they caused to those their commanders called the enemy while fighting Washington’s war.

I had another friend named Loren. Like so many others, he was drafted into the Army against his will. When he got his orders to go to Vietnam, he took a truck from the motor pool where he worked and ran it through several gates and a couple of parked cars in the Officer’s Club parking lot at the Colorado Army base he was stationed. He did six months in the stockade and was thrown out of the Army. He celebrated by going to a rock festival and ended up in Berkeley. His father didn’t speak to him for years, but it was worth it to Loren just to have avoided the war. After reading Things We Do To Make It Home, one wishes once again that more soldiers would follow Loren’s example and just refuse to fight.