On January 1, 1994, the now-infamous North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect. That same day, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), rose up and launched a military offensive that occupied towns throughout the state of Chiapas, in Mexico. The EZLN, or “Zapatistas” had been covertly organizing for many years, but they specifically chose the day of NAFTA’s implementation for their public rebellion.

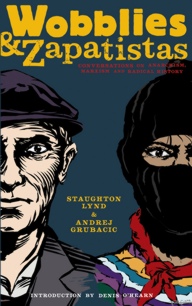

Many components of NAFTA favored US corporate interests at the expense of Mexico’s general population, but the Zapatistas were particularly opposed to NAFTA’s rewriting of the Mexican Constitution, in order to eliminate the population’s biggest victory won during the Mexican Revolution fought years before, at the time of World War One. “The Mexican Revolution wrote into the national constitution the opportunity for a village to hold its land communally, in an ejido, so that no individual could alienate any portion of it,” writes Staughton Lynd, ((Staughton Lynd taught American history at Spelman College and Yale University. He was director of Freedom Schools in the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer. An early leader of the movement against the Vietnam War, he was blacklisted and unable to continue as an academic. He then became a lawyer, and in this capacity has assisted rank-and-file workers and prisoners for the past thirty years. He has written, edited, or co-edited with his wife Alice Lynd more than a dozen books. )) co-author of the new book Wobblies and Zapatistas: Conversations on Anarchism, Marxism and Radical History. Both Lynd (a Marxist from the US) and his co-author Andrej Grubacic ((Andrej Grubacic is a dissident from the Balkans. A radical historian and sociologist, he is the author of Globalization and Refusal and the forthcoming titles: Hidden History of American Democracy and The Staughton Lynd Reader. A fellow traveler of Zapatista-inspired direct action movements, in particular Peoples’ Global Action, and a co-founder of Global Balkans Network and Balkan Z Magazine, he is a visiting professor of sociology at the University of San Francisco.)) (an anarchist from the Balkans) are public supporters of the Zapatistas, who they argue have set a powerful example of revolutionary organizing that should influence anti-capitalists around the world. Much like the historical traditions of the Haymarket Martyrs and the ‘Wobblies’ (the Industrial Workers of the World) in the United States, Lynd and Grubacic argue that the Zapatistas have synthesized the best aspects of both the Marxist and anarchist traditions.

Based upon his research and his personal travels to the Zapatista communities in Chiapas where he met with historian Teresa Ortiz, Staughton Lynd identifies three key “sources of Zapatismo.” First, is the issue of land. Before NAFTA, the communal lands called ejidos made up more than half of Mexico’s land. The day of the 1994 uprising, the Zapatistas occupied formerly communal lands that had been appropriated. Directly citing the legacy of the Mexican Revolution, the Zapatistas named themselves after Emiliano Zapata, an anarchist revolutionary who was a key figure in the Mexican Revolution, and whose popular slogan “Land and Liberty” is still heard today.

Second, Lynd identifies a form of Liberation Theology that is influenced by both Christian and Native American spirituality, with Bishop Samuel Ruiz being a key figure.

“The final and most intriguing component of Zapatismo, according to Teresa Ortiz was the Mayan tradition of mandar obediciendo, ‘to lead by obeying’…When representatives thus chosen are asked to take part in regional gatherings, they will be instructed delegates. If new questions arise, the delegates will be obliged to return to their constituents. Thus, in the midst of the negotiations mediated by Bishop Ruiz in early 1994, the Zapatista delegates said they would have to interrupt the talks to consult the villages to which they were accountable, a process that took several weeks. The heart of the political process remains the gathered residents of each village, the asemblea,” writes Lynd.

This anti-authoritarian tradition of mandar obediciendo was central to the Zapatista’s decision not to see themselves as a revolutionary vanguard. Lynd explains that “beginning in early 1994, Marcos said explicitly, over and over again: We don’t see ourselves as a vanguard and we don’t want to take power.” To support his argument, Lynd cites a variety of statements from Marcos, including his August 1994 statement at the National Democratic Convention in the Lacandon Jungle. Here, Marcos proclaimed that the Zapatistas had decided “not to impose our point of view,” and that they had rejected “the doubtful honor of being the historical vanguard of the multiple vanguards that plague us…Yes, the moment has come to say to everyone that we neither want, nor are we able, to occupy the place that some hope we will occupy, the place from which all opinions will come, all the answers, all the routes, all the truth. We are not going to do that.”

Lynd, coming from the Marxist perspective, harshly criticizes the influence of vanguard politics on Marxist revolutionary movements, whereby these movements have adopted authoritarian and anti-democratic practices, with these abuses of power being justified by the argument that their particular group is the vanguard of the revolution, and is therefore entitled to lead the revolution as it sees fit. Lynd sees the Zapatista’s rejection of vanguard politics as representing a “fresh synthesis of what is best in the Marxist and anarchist traditions.” The Zapatistas, Lynd writes, “have given us a new hypothesis. It combines Marxist analysis of the dynamics of capitalism with a traditional spirituality, whether Native American or Christian, or a combination of the two. It rejects the goal of taking state power and sets forth the objective of building a horizontal network of centers of self-activity. Above all the Zapatistas have encouraged young people all over the earth to affirm: We must have a qualitatively different society! Another world is possible! Let us begin to create it, here and now!”

Wobblies and Zapatistas is highly recommended to both the seasoned fan of books about radical history and theory, and the reader who is just now becoming interested in radical politics. While rooted in the inspirational examples of both the Wobblies and the Zapatistas, this book uses refreshing language and an informal conversational format of Grubacic interviewing Lynd. Their dialogue provides a big picture of global struggles against capitalism, and all forms of oppression. I myself learned for the first time that in the US, both the Haymarket anarchists of the late 1800s, and the anarchist Wobblies of the early 1900s were heavily influenced by Marxism. I also learned that many Marxists, such as Rosa Luxemburg from Germany, were themselves very critical of the anti-democratic and elitist consequences of the vanguard strategy of organizing that has been embraced by so many Marxists.

Wobblies and Zapatistas is highly recommended to both the seasoned fan of books about radical history and theory, and the reader who is just now becoming interested in radical politics. While rooted in the inspirational examples of both the Wobblies and the Zapatistas, this book uses refreshing language and an informal conversational format of Grubacic interviewing Lynd. Their dialogue provides a big picture of global struggles against capitalism, and all forms of oppression. I myself learned for the first time that in the US, both the Haymarket anarchists of the late 1800s, and the anarchist Wobblies of the early 1900s were heavily influenced by Marxism. I also learned that many Marxists, such as Rosa Luxemburg from Germany, were themselves very critical of the anti-democratic and elitist consequences of the vanguard strategy of organizing that has been embraced by so many Marxists.

Lynd and Grubacic’s exploration of the relationship between Marxism and anarchism is played out through their examination of so many fascinating stories of popular rebellion throughout world history. Many of these stories are about workers’ rebellions, but Lynd emphasizes that while the role of workers in making revolution is very important, workers are only part of the big picture, and workers should not be prioritized over other parts of society, including prisoners, students, women, and racially oppressed groups. Lynd summarizes his theory for best making revolutionary change: “We are all leaders, not just as a collection of individuals, but as persons embedded in different kinds of institutions and communities of struggle. The framework with within which all these aspirations must be lodged is the collective action, not of taking state power, but of building down below a horizontal network of groups and persons that is strong enough to command the attention of whoever is in government office.”

To accompany this book review, I interviewed co-author Staughton Lynd, asking him these four questions below.

Hans Bennett: This decade in Latin America has seen so many successful poor people’s movements. Are you particularly inspired by any of these victories? How do these embody those traits that you spotlight as so positive regarding the Zapatista movement?

Staughton Lynd: As your question suggests, the most hopeful part of the earth during this past decade has been Latin America. The Zapatista movement seems the most significant effort, but I believe it is organically connected to movements in other countries that have elected Leftist governments. The Zapatistas speak of governing in obedience to those below, “mandar obediciendo.” The Zapatistas interpret these words to direct them not to try to take state power, but instead to create a horizontal network of self-governing communities sufficiently strong that the national government will have to pay attention to “the below” and be accountable to it. However, in Bolivia when Evo Morales became president, he said in his inaugural speech that he intended to “mandar obediciendo”: that is, he accepted the Zapatista formulation as to how it should be between elected officials and the electorate, and in his capacity as an elected official, he intended to try to live up to it.

HB: How can US organizers adopt the Zapatista’s approach?

SL: The fundamental problem is that unlike the Zapatistas we do not have communities that have existed for centuries, that make decisions by consensus, that designate many persons to undertake small tasks or “cargos” for the community, that understand the first obligation of an elected representative to be listening, not talking. Instead, “organizing” in the United States is invariably quasi-Alinskyan, that is, inspired by the methods of Saul Alinsky, who in turn modeled his work on trade union organizing in the 1930s. I was one of four original teachers at Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation Training Institute founded in 1968-1969, and am an historian of the labor movement in the 1930s, so I think I know whereof I speak. The Alinsky approach assumes that people are motivated by individual, short-term, primarily economic self-interest. “Solidarity unionism” instead encourages people to take small steps in the interest of the group as a whole: for example, in a layoff to share the pain equally rather than strictly applying seniority.

HB: Given that we’re living in the “belly of the beast,” how do you think we in the US can best support Latin America poor people’s struggles that are resisting both their local ruling class, and US influence/dominance?

SL: Support for radical or revolutionary movements in other countries is a tricky undertaking. The Left in the United States has over and over again fallen into the error of romanticizing foreign movements and regimes. Examples are: the Soviet Union, revolutionary Cuba, the National Liberation Front in Vietnam, Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, and perhaps now, the Zapatistas. I believe what is helpful is to say, ‘The United States should cease to intervene in Country X,’ but not, ‘We unreservedly favor whatever insurgent movement exists there.’ We should have learned this from the period of the Vietnam war. As soon as the Vietnamese had driven out the United States they created “re-education camps” against which I, at least, felt obligated to protest. Similarly, when the Sandinista government was voted out of office in 1990, Margaret Randall exposed the fact that a handful of men had run everything, including AMNLAE, which presented itself as a women’s organization. So we in the US are better off when we support the withdrawal of US troops, closing of US military bases, the nationalization of US private investments, but do not try to control what happens next.

HB: Given today’s “global economy,” do you know of any examples of any US workers being involved with cross-border working class organizing?

SL: Cross-border organizing has been timid and bureaucratic. I would like to see, for example, General Motors workers in Mexico, Canada and the United States strike together. The demands of each national group of workers would be somewhat different, but so what? Instead, even reform movements in American trade unions acquiesce in chauvinism. Thus Teamsters for a Democratic Union tries to keep Mexican truck drivers from entering the United States, even though (a) NAFTA requires their admission, (b) simple solidarity would suggest that if Iowa corn farmers can take advantage of NAFTA to destroy the livelihoods of countless Mexican campesinos by exporting corn to Mexico without import duties, then truck drivers in the United States should meet with their Mexican counterparts and seek solutions that benefit all workers involved.