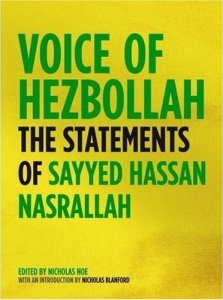

Voice of Hezbollah: The Statements of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah

Edited by Nicholas Noe

(Verso: 2007), 420 p

ISBN: 978 1 84467 153 3

Since the assassination in Damascus of Imad Mughniyeh, a leading Hizbullah operative, a sense of foreboding once again grips Lebanon. The Hizbullah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah says the bombing foreshadows Israeli aggression and has declared his willingness to wage ‘open war’ should there be another invasion. Fighting words are not uncommon to the region; leaders often compensate for lack of action with bravado. However, no one is ready to discount the significance of Nasrallah’s statement. Why?

As the Israeli Air Force decimated the exposed Egyptian infantry in 1967 Nasser’s propagandists were forecasting success. When the US-UK air armada pummelled the hapless conscripts of the Iraqi army in ’91, Saddam’s propaganda mill promised imminent victory (which it duly claimed shortly after signing unconditional surrender). Likewise, Saddam’s Minister of Information greeted the US-UK invasion in 2003 with similar fanciful flourishes. An object of frequent ridicule, such mendacity is often adduced by born-again Orientalists as a function of the addled ‘Arab mind’. That is, until one voice emerged that undermined stereotypes and restored dignity and trust.

Syed Hassan Nasrallah, the Secretary General of the Lebanese Hizbullah movement, has established a reputation for saying only what he means and promising only what he is able to deliver. Islamic Resistance, the guerrilla wing of Hizbullah, has evolved under his helm from its ragtag origins to the world’s most effective resistance movement, twice defeating the vaunted Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) in battle. As a testament to his intelligence and organization skills, Hizbullah has also developed an efficient and extensive social service network — hospitals, educational institutions, a construction company and its own media — that caters to its mostly impoverished Shia constituency. As a result he has emerged as the most popular figure in the Middle East. The Syrian Bashar al-Assad according to Seymour Hersh claims to be in ‘awe of Nasrallah’ and ‘worships at his feet’. Secular MPs in Egypt revere him as an ‘heir to Saladin’. Christian divas in Lebanon have immortalized him in song. The modest Shia cleric is a living legend in the mostly Sunni Middle East.

Despite its regional popularity, Hizbullah remains a largely misunderstood phenomenon in the West where media demonology often conflates Hizbullah with al-Qaeda and Nasrallah with Usama bin Laden. Few in Europe or the US have heard Nasrallah’s voice. This may largely be due to the fact that all his speeches are delivered in Arabic. It is to introduce the Anglophone world to this important voice that Nicholas Noe has collected Nasrallah’s speeches and interviews spanning two decades in Voice of Hezbollah: The Statements of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah. With a competent translation by Ellen Khouri, the interviews and speeches elaborate on key events in Lebanon’s recent history. Nasrallah’s pronouncements are invariably thoughtful, nuanced and carefully worded, eloquence rarely giving way to rhetoric. At times fiery, they remain grounded in fact, and adversaries often ignore his promises at their own peril. The book reveals a methodical mind explicating on historical events and developments with an impressive attention to detail. The significance of some of the events may have diminished, however the chronologically ordered interviews offer useful insights into the strategic shifts in the movement’s outlook and the intellectual evolution of its leader.

Despite its regional popularity, Hizbullah remains a largely misunderstood phenomenon in the West where media demonology often conflates Hizbullah with al-Qaeda and Nasrallah with Usama bin Laden. Few in Europe or the US have heard Nasrallah’s voice. This may largely be due to the fact that all his speeches are delivered in Arabic. It is to introduce the Anglophone world to this important voice that Nicholas Noe has collected Nasrallah’s speeches and interviews spanning two decades in Voice of Hezbollah: The Statements of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah. With a competent translation by Ellen Khouri, the interviews and speeches elaborate on key events in Lebanon’s recent history. Nasrallah’s pronouncements are invariably thoughtful, nuanced and carefully worded, eloquence rarely giving way to rhetoric. At times fiery, they remain grounded in fact, and adversaries often ignore his promises at their own peril. The book reveals a methodical mind explicating on historical events and developments with an impressive attention to detail. The significance of some of the events may have diminished, however the chronologically ordered interviews offer useful insights into the strategic shifts in the movement’s outlook and the intellectual evolution of its leader.

Born on 31 August 1960 to an impoverished fruit vendor in Karantina, East Beirut, Nasrallah was drawn to religion and intellectual endeavour from an early age. Ninth in a family of ten children, the young Nasrallah would frequent walk to the city centre to purchase second-hand books and unlike his peers would devote all his time to reading. An early influence on Nasrallah’s thinking was the Iranian born Lebanese cleric Imam Musa al-Sadr. In Lebanon’s long history of civil strife, its mostly underprivileged Shia population has remained largely marginal. The confessional balance of the political system based on a 1932 census of dubious merit accords the Shia a subordinate role. It was the Harkat al-Mahrumin (Movement of the Disinherited) of Musa al-Sadr that first empowered the Shia and challenged the entrenched feudal elite lording over it. The movement also evolved an armed wing, Afwaj al-Muqawama Al-Lubnaniyya, better known as Amal.

The civil war of 1975 forced the Nasrallah family to relocate to its ancestral home in Bazouriyeh, South Lebanon, where Nasrallah joined the nascent Amal movement soon after finishing school in Tyre. At age fifteen, the precocious youth was appointed head of the movement for his home town, until then a secular leftist redoubt. Nasrallah founded a library at the local Islamic Centre where young men and women would come and receive education, also imbibing the revolutionary teachings of Musa al-Sadr.

In 1976 Nasrallah headed to Najaf in Iraq to complete his religious education under Baqr al-Sadr (executed in 1980 by Saddam, he was the Father-in-law of Iraqi leader Muqtada al-Sadr). On al-Sadr’s instruction Nasrallah was taken under the wings by another one of his Lebanese disciples, Sheikh Abbas Mussawi with whom Nasrallah would later found Hizbullah. The man who Nasrallah would recall as a ‘friend, brother, mentor and companion’ would assist him through the ascetic seminary life where the new pupil’s hard work would lead him to finish preliminary instruction in two years, rather than the usual five. It was in Najaf that Nasrallah was first introduced to the teachings of Ayatollah Khomeini, who departed from the traditional quietist Shia theology in his concept of wilayat al-faqih -– the rule of the jurist-theologian -– which prescribed the supreme authority of the faqih over an Islamic state. To this day Hizbullah remains faithful to this concept, even though it has since abjured its call for the creation of an Islamic state as part of its ‘Lebanonization’ process begun in the 90s.

Nasrallah escaped the Baathist crackdown on Shia seminaries in ’77 and arrived back in Lebanon in ’78 to take up his education at an institution set up by Mussawi in Ba’albek. His return coincided with the Israeli invasion and two other events of immeasurable import –- the disappearance of Imam Musa al-Sadr, and the Islamic revolution in Iran -– that led him to resume his political activities. By the late 70s Amal’s power, already circumscribed, was on the wane as a result of political myopia. It was only the mysterious disappearance of al-Sadr in 1978 (presumably assassinated by Libya’s Gaddafi) that revived its fortunes. By the time Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982, Nasrallah had become the head of Amal for the Bekaa region and member of its Central Committee.

It was around the same time that PLO had decamped to South Lebanon after the events of Black September in 1970. It initially challenged the entrenched elite -– mainly Sunnis and Maronites -– leading many Shia to flock to its ranks. Relations soured over time as the majority Shia population of south Lebanon was caught between the armed and often domineering presence of the PLO and the indiscriminate Israeli attacks from across the border. Amal, which was initially trained by the PLO, soon allied itself with Syria and intervened to thwart a Palestinian victory over Maronite militias in 1976. By the time Israel invaded Lebanon, the local population was so resentful of the PLO presence that many greeted advancing Israelis tanks with perfumed rice and flowers. Nabih Berri, the leader of Amal, sought a modus vivendi with the Israeli occupiers and joined the collaborationist ‘national salvation’ government (It wouldn’t be until 1983 that an Israeli patrol’s attack on an Ashura procession in Nabatiyah would lead Amal to join the resistance).

It was this initial failure of Amal to confront the Israeli occupation that led a faction led by Nasrallah and Mussawi to split and form the core of what would later emerge as Hizbullah. In Pity the Nation, Robert Fisk’s magisterial account of the Lebanon war, the veteran Middle Easter correspondent describes the first Israeli encounter with this new force.

Some of the Shia fighters had torn off pieces of their shirts and wrapped them around their heads as bands of martyrdom… When they set fire to one Israeli armoured vehicle, the gunmen were emboldened to advance further. None of us… realised the critical importance of the events of Khalde that night. The Lebanese Shia were learning the principles of martyrdom and putting them into practice… It was the beginning of a legend which also contained a strong element of the truth. The Shia were now the Lebanese resistance, nationalist no doubt but also inspired by their religion. The party of God –- in Arabic, the Hezbollah –- were on the beaches of Khalde that night.

The improvisations soon gave way to disciplined guerrilla warfare after Ayatollah Khomeini dispatched a contingent of 1,500 Iranian Revolutionary Guards in summer 1982 to train volunteers in the Bekaa Valley. Nasrallah played a key role in recruiting young Shia volunteers, and by 1985 had assumed leadership of Hizbullah in the Bekaa valley.

Deadly attacks were launched in the intervening years by a group calling itself Islamic Jihad allegedly linked to Hizbullah that targeted the US embassy and marine barracks. The latter there purportedly to keep peace had soon joined the conflict on side of the Israeli proxies in Lebanon. French paratroopers suffered a similar fate, leading to the withdrawal of the Multi-national Force. A successful strike on the Israeli head quarters in Lebanon that killed 72 Israeli soldiers also precipitated its retreat to the South where it maintained occupation of a narrow ‘security zone’. Continually harried by Hizbullah, it would eventually end its costly occupation in 2000.

It wasn’t until 1985 that Hizbullah emerged as a coherent organization announcing its formal existence in the form of an Open Letter which also served as its manifesto. Established with an avowedly pan-Islamic outlook adhering to Khomeini’s Wilayat al-Faqih doctrine, the movement has since emphasized its distinctly Lebanese nationalist credentials with its ambitions limited to the liberation of occupied Lebanese territory and defence of the realm in the absence of a strong national army. Leading figures in the movement have hinted that the Open Letter belonged to a specific period in time and does not reflect Hizbullah’s present political stance.

Nasrallah, who had since moved to Beirut, first came to prominence when he started giving speeches and interviews after being appointed to the consultative council of Hizbullah in 1987. A year later came the first Israeli assassination attempt. Hizbullah, which, unlike other Lebanese groups, had avoided confessional/sectarian war to focus solely on resisting the occupiers, found itself for the first time embroiled in a turf battle with Amal in Beirut and South Lebanon. These animosities survived well into the 90s and would only be resolved when Hizbullah and Amal would join a coalition against the US-backed forces jockeying for control after the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in 2005.

Although Hizbullah signed on to the Arab League-borkered Taif Accords that ended the Lebanese Civil War in 1989 they refused to relinquish arms. The pragmatist Nasrallah and Mussawi’s decision to participate in Lebanese politics also led to a high-level split when Subhi Tufeili the first Secretary General of Hizbullah chose to part ways rather than participate in the confessional political system. He was replaced by Mussawi as Hizbullah’s new secretary general. Hizbullah emerged with 12 seats in the 1992 parliamentary elections, a mark of the movements growing popular base in the Bekaa valley and the South.

Hizbullah continued its low-intensity war where it was careful to confine its activities to the occupied South. Israel however was less constrained: Mussawi was assassinated along with his family by an Israeli gunship in 1992 leading to Nasrallah being elected as the new Secretary General of Hizbullah. Nasrallah soon moved to modernize the resistance, ushering in a tactical revolution. Journalist Nicholas Blanford writes, that underr Nasrallah’s leadership, ‘the resistance became more compartmentalized, with units specializing in different weapons and tactics. Intelligence-gathering measures were improved and greater autonomy given to field commanders.’

These resulted in a nearly twenty-fold increase in the rate-of- attack on the Israeli occupation forces by the end of the decade, whereas the fatality ratio dropped from an average of five-to-one in 1990 to three-to-two by the end of the decade. Israel responded with several major attacks, beginning with ‘Operation Accountability’ in 1993, and ‘Operation Grapes of Wrath’ in 1996 which culminated in the massacre of a hundred refugees at a UN compound in Qana by Israeli artillery (Nasrallah’s own 18-year-old son Hadi was killed in 1997 resisting the Israelis). The operations in 1999 and February 2000 were equally disastrous for Israel. Meanwhile, its proxies in the SLA continued their routine torture and harassment in the occupied South.

Hizbullah’s biggest success came on May 24, 2000 when Israel’s 22 year occupation of South Lebanon collapsed overnight and soldiers retreated behind the border. It was the first victory over Israel of any Arab force, and it was celebrated all over the Middle East. Yet it presented Hizbullah with an existential dilemma. Pressure was growing on Hizbullah to disarm as it had achieved its stated goal of liberating Lebanese occupied territory. In the debate over whether to continue the armed struggle or to shift focus completely to socio-political issues Nasrallah opted for the former. However this required a pretext which was furnished in the form of the Shebaa farms, a narrow strip of the occupied Golan Heights claimed by Lebanon. With Israel’s continued occupation of the farms, Hizbullah had a rationale for resistance.

The years between Israel’s retreat and the commencement of hostilities in 2006 saw very little combat. Israel continued its violation of Lebanese airspace with the occasional kidnapping of Lebanese fishers and farmers while Hizbullah managed to kill 17 more Israeli soldiers. Under the cover of the stabilizing Syrian presence there since the end of the Civil War, Hizbullah was able to avoid the messy parochial politics of Lebanon in favour of continued resistance. However, the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in February 2005 came as a major rupture with the past.

The mass protests in the wake of the assassination demanding an end to the long standing Syrian presence in Lebanon culminated in the ‘cedar revolution’ (a phrase coined by a US State Department official). With US-French backing, the so called March 14 movement, comprising mainly Sunni and Christian Maronite parties, succeeded in getting Syria to withdraw from Lebanon. Conscious that the vacuum left by the Syrian withdrawal may be filled by a US-Isareli hegemony given the pro-US orientation of the March 14 Alliance newly elected to power, Hizbullah forged strategic alliances to protect its interests. It buried the hatchet with Amal to forge an alliance that allowed it to join the government where it held 5 cabinet seats. Nasrallah has since succeeded in negotiating another strategic alliance with anti-Syrian Christian Maronite Free Patriotic Movement of General Michel Aoun.

Contrary to the prevailing media myth, the relationship between Hizbullah and Syria is mostly strategic, and their interests often diverge. Hizbullah sided with the Palestinians against the Syrian-backed Amal during the ‘war of the camps’; In the 1988-89 Hizbullah-Amal conflict Syria once against backed its rival. In ’87 the al-Asad regime also had 23 Hizbullah men killed. Hizbullah is also aware that any peace agreement between Syria and Israel may come at its expense. The same is also true of US-Iran rapprochement: the Iranian peace offer to the United States in 2003 included a pledge to withdraw support for Hizbullah. The last Iranian Revolutioanrly Guard advisers left Lebanon in 1998. Hizbullah has since emerged as a fully autonomous movement, thoroughly Lebanese in its outlook. Today it is not so much its reliance on Iran and Syria that is of higher import, but the reliance of the two on Hizbullah.

Although Nasrallah had twice negotiated successful prisoner swaps in ’96 and ’98 using German intermediaries, in 2004 he scored a major coup when in return for the bodies of three Israeli soldiers and one captured officer, Hizbullah succeed in securing the release of 23 Lebanese and 400 Palestinian prisoners. However several Lebanese prisoners still remained in Israeli custody. In 2006 Nasrallah warned that unless Israel released these prisoners, he would have no choice but to capture more Israelis for another exchange. At 9:04 on the morning of July 12 Hizbullah guerrillas delivered on the promise by capturing two Israeli soldiers and killing eight more in the ensuing firefight. A Merkava tank sent in pursuit was also blown up. This precipitated the heaviest bombing of Lebanon by Israel since its invasion of 1982.

The war saw Israel wreak mass destruction on the Lebanese civilian population, even as on the battlefield its performance remained dismal. Hizbullah withstood the air blitz and with its unrelenting barrage of rockets drew Israel into committing ground troops. The vaunted IDF with all its advanced weaponry soon found itself outclassed by Hizbullah’s iron discipline. With little to show for the mounting losses, Israel was forced to progressively climb down from its earlier maximalist aims, eventually agreeing to a ceasefire that merely restored the status quo ante.

Al-Manar continued its broadcasts uninterrupted through the conflict, and Nasrallah appeared on-air frequently giving reports on the progress of the war in his characteristic understated, factual manner (one such appearance ended with Nasrallah dramatically asking viewers to step outside their homes and look West where they were presented with the sight of a burning Israeli ship off the Lebanese coastline just targeted by a Hizbullah missile). During the war more Israelis tuned in to al-Manar than their own national TV. This time it was the Israelis turn to suffer the indignity of repeated claims of success by their leaders which would be subsequently discredited by events.

By the time Israel retreated back to its border it had left a hundred and twenty soldiers dead, forty of its tanks and armored vehicles destroyed and one helicopter downed. For Israel it was a humiliating defeat, and an end of its deterrence capabilities. Hizbullah emerged stronger and more popular than before. Its immediate and efficient assistance to those who had lost property during the war further added to its popularity.Critics who had accused it of precipitating the war –- including the inimitable Robert Fisk -– would be proven wrong by Israel’s own official inquiry into the war -– the Winograd Committee report –- which confirmed that the war had been planned by Israel more than a year ahead. As the Guardian reported, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s testimony to the commission ‘contradicted the impression at the time that Israel was provoked into a battle for which it was ill-prepared.’

In a country caught between its own factional rivalries and the perennial intervention of foreign powers, principle is often a dispensable commodity. Yet much of Hizbullah’s regional prestige derives from its ability to take difficult decisions in the face of impossible odds. Established as a rejection of the kind of realpolitik embraced by Amal, the existing Shia movement, Hizbullah has not shied away from taking difficult positions, such as its defence of the Palestinians against its Syrian backed Shia rival. Through al-Manar, Hizbullah has continued to present its successful resistance as a model for Palestinians in the occupied territories, at times actively intervening on their behalf. It responded to the March 22, 2004 assassination of Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, the quadriplegic spiritual leader of Hamas with a barrage of more than 60 rockets at six different Israeli military positions in the Shebaa farms. Similarly in 2006 the timing of its raid was widely seen as intended to relieve pressure on Gaza under brutal assault at the moment (in this instance however it had the contrary effect as under the cover of the Lebanon war, Israel was able to get away with more murder).

In 2007 when the Lebanese military began its assault on the Palestinian refugee camp of Nahr al-Bared in order to crush a small band of Sunni militants, Fatah al-Islam, Nasrallah had to tread the fine line yet again. Most of Lebanon seemed indifferent to the plight of the innocent Palestinians caught in the crossfire, and even his political ally, the nationalist general Michel Aoun supported unrestrained action. Nasrallah’s qualified statement of support however declared the Palestinian refugees a ‘red line’ as the Lebanese army was a red line. Neither need be crossed. This drew shrill condemnation from the US-backed Lebanese opposition who accused him of insufficient patriotism for not offering unconditional support.

The 2007 US National Intelligence Estimate has put a spanner in the neoconservative plan for a new war by confirming that Iran has no nuclear weapons program. However, attempts to curb Iran’s mythical influence have continued apace. Israel’s humiliating defeat at the hands of Hizbullah have led its supporters in the US to back a new ‘redirection’ plan, as reported by the legendary journalist Seymour Hersh. This has included arming hard line Sunni militants to confront Hizbullah (in Iraq US precipitated a civil war by doing the opposite: arming Shias against the Sunni insurgency) and a wider propaganda campaign to sow fears of an emerging ‘shia crescent’. In Lebanon this went awry when the militants started showing more interest in fighting Israel than Hizbullah. The Fatah al-Islam episode further sealed its fate.

The Sunni Arab leaders of the Egypt and Jordan (and to a lesser degree Saudi Arabi)have played along. As journalist Patrick Cockburn observes, they ‘were embarrassed by the success of the Shia

Hizbollah in the war in Lebanon… compared to their own supine incompetence.’ In the wake of the 2006 invasion of Lebanon where the Saudi, Jordanian and Egyptian leadership tacitly sided with Israel, a poll found Nasrallah and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad the two most popular leaders in Egypt. This is all the more remarkable given the fact that both are Shia, whereas the leadership of the largely Sunni Egypt has long played on sectarian differences to deflect its own sordid role in sustaining US-Israeli hegemony.

Since 2006 Hizbullah has led the opposition in a non-violent protest against the government demanding fairer representation. Detractors have tried to portray this as a coup against the government, and Nasrallah’s demand for a one-man-one-vote system as somehow outlandish. A deadlock has prevented the appointment of a new President, and the political future remains as yet uncertain. Forces of status quo resent Hizbullah’s assertiveness, but more so its status as a global player where they on the other hand remain perpetually identified with their parochial concerns. The government, backed by its supporters in the West and among the Arab states, has thus far prevented Hizbullah translating its military victory into political gains. While the people of the Middle East idolize Hizbullah, for their leaders the movement presents the threat of a good example. It is not yet confirmed who assassinated Imad Mughniyeh, but Israel is not alone in wishing to see Nasrallah and his movement humbled. Should there be a war, it would be interesting to see how the different forces line up. For now, the only thing that remains certain is that whatever happens in Lebanon, its borders are too small to contain the impact.