There was nothing of First Nations [sic] language, culture or history taught to the children at the residential school. The purpose of the residential schools was to do away with First Nations’ language and culture and to assimilate the children into white society.

On 13 September 2007, the United Nations adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (DRIP). It was carried by the UN General Assembly despite the shameful nay-vote cast by Canada (along with nay-votes from other colonized and occupied states such as Australia, New Zealand, and the United States).

The Declaration sets standards for the treatment of Indigenous Peoples that should provide a framework for the protection of their human rights. The DRIP is non-binding, as is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, so adherence to the Declaration is compelled only by a state’s sense of morality and concern for its reputation in the eyes of the world.

Canada’s minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, Chuck Strahl, complained about the DRIP: “It’s not balanced, in our view, and inconsistent with the Charter [of Rights and Freedoms].”

The opposition of Canadian authorities to the DRIP is understandable in light of how Canada came about. Canada is a state founded on the dispossession of its Original Peoples. The dispossession is ongoing.[efn_note]See Robert Davis and Mark Zannis, The Genocide Machine in Canada: The Pacification of the North (Toronto: Black Rose, 1973).[/efn_note]

A major plank in the Canadian government’s program has been the assimilation of the Original Peoples. This was clearly demonstrated by the state’s removal of indigenous children from their homes and families and placing them in a residential school system which sought to replace indigenous languages, religion, and culture with English language, Christianity, and western culture.

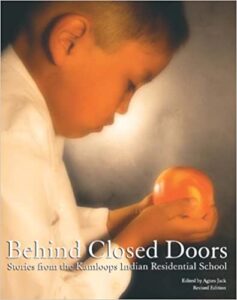

Behind Closed Doors: Stories from the Kamloops Indian Residential School, edited by Agnes Jack, is a collection of 32 stories as told by Original Peoples of their own experiences in the residential school system.

The Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS) was situated in Kamloops — a small city in the south-central part of the province dubbed “British Columbia.” The KIRS, which operated from 1893 until it was closed in 1977, was part of the government’s assimilationist policy.

The story tellers relate accounts of a learned dysfuntionality from the KIRS which perpetuated itself through generations of Original Peoples.

The dysfunctionality originated in the treatment at the school. Individuality was stripped from the children by shearing their long hair, wearing of uniforms, and strict separation of girls and boys, even of family members.

There are tales of loneliness, long hours of labor, and harsh discipline that included beatings.

Said former KIRS student William Brewer, “[T]hey’d beat you up if you spoke your language. Most of them kids that were coming to that school, they could hardly speak English in them days.”

Ex-KIRS student Mary Anderson lamented, “No one got a comfort of any kind [at the school].” There were no hot baths; the building was cold; and the food was inferior, gristly, and sour.

Dorothy Jones recalled, “The teachers called us savages.”[efn_note]For another perspective on who the savages were, see Daniel N. Paul’s We Were Not the Savages: A Mi’kmaq Perspective on the Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations (Nova Scotia: Fernwood Books, 2000).[/efn_note]

Former KIRS student Robert Simon described the school as a prison: “I don’t know what else it could be described as other than a jail. Any place that holds you against your will, punishes you and sets up rules to totally retrain your thinking.”

There were sports, dances, and movie nights. Movie nights at the school often featured John Wayne defeating the Indian savages. Indigenous dances were eschewed in favor of dances chosen by the school clergy. Horribly, there are also tales of sexual molestation and rapes suffered by the children.

Simon rued that the churches have not taken responsibility for their role in the assimilation of indigenous children.

Ron Ignace told of millennial-old indigenous languages, repositories of “vast amounts of intellectual knowledge representing a great reservoir of cultural heritage” that were “driven to the brink of extinction by Canada.” Ignace noted that Canada has done little to right this wrong, and, as a consequence, indigenous languages are still threatened.

Wanye Christinson said, “The residential schools are our holocaust. The government forcibly confined and rendered our people powerless by their laws and policies of cultural genocide. We are speaking of 150 years of trauma and horror where our children were systematically brainwashed to not resist the government’s legislation of assimilation and genocide.”

Despite this, the hardiness of many children that attended the residential schools shows them to be survivors. Telling of the tribulations in the residential school was part of the catharsis of survival.

Behind Closed Doors is a first hand history that all Canadians should be familiar with. If diasporic Canadians become aware of how Canada was established and is being further developed by trampling on Indigenous rights, would morality guide a national conscience and reach out to the Original Peoples? Becoming aware is the first step.

ENDNOTES