In recent weeks protests against the elected president Nicolás Maduro have captured the imaginations of corporate media outlets and wealthy expatriates alike. Hyper sensationalist propagandists like Francisco Toro, in his blog article “The Game Changed Last Night” that has made its way around social-media networks, regurgitated blatant falsehoods, suggesting that “state-sponsored paramilitaries on motorcycles” were “roaming middle class neighborhoods… shooting at anyone who seemed like he might be protesting.” In reality, by February 21 a total of ten people had died in Venezuela due in one way or another to the clashes. Of these, two were due to motor vehicle accidents stemming from drivers attempting to avoid opposition barricades, another was the assassination of a brother of a Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV, Maduro’s party) parliamentary deputy, and yet another is apparently the result of “friendly fire” from the ranks of the opposition. ((Ewan Robertson, “Death Toll in Venezuela Clashes Rises to Ten” (Updated).)) The reality is a far cry from the narrative of a brutal, repressive regime clamping down violently on student protest.

The purpose of this piece is not to explore the dynamics of the student protests, which can be read about ad nauseam elsewhere. Instead, it is meant to help illuminate the role that wealthy expatriates play in propagating a narrative conducive to their own and, by extension, U.S. interests in Venezuela. It must be noted that this is by no means a definitive account. It is at best a cursory reflection based partly on personal experience, one in which I hope will encourage others to explore the role of their own local student organizations in dictating the narrative on Venezuela. However, it appears likely that the composition of Latino student organizations, given the influx of privileged Venezuelan students on U.S. campuses, has played a key role in dictating the narrative surrounding events in Venezuela.

First, it is important to briefly review the sort of changes that have occurred in Venezuela since the late 1990s. An exodus of Venezuela’s rich came almost immediately after Hugo Chávez won his first election and assumed the presidency in 1999. By August of 2000, the Miami Herald reported that some 180,000 had fled the country, with the vice-president of sales at the Ocean Club resort community in Florida suggesting “more Venezuelans than usual” had been purchasing condominiums. ((Alfonso Chardy, “Wealthy Latin American immigrants seek refuge in South Florida.”)) The New York Times reported that the growth of Venezuelans in South Florida from 2000 to 2006 was 118%, one of the highest growth rates for all Latino immigrants. ((Kirk Semple, “Rise of Chávez Sends Venezuelans to Florida.”)) By 2012, around one million Venezuelans had left, mostly destined for the United States, Canada, and Australia. ((Charlie Devereux and Daniel Cancel, “Chávez Win Spurs Exodus as Venezuelans Foresee Economic Woes.”)) More than 500,000 left in 2010 alone. Yet, it should be noted, during the same year Venezuela took in almost double the amount of immigrants from Colombia, Haiti, and other countries. Although no comprehensive statistical analysis of those leaving Venezuela appears readily available, media coverage and anecdotal evidence suggests that the ones leaving Venezuela are disproportionately those with the wealth and privilege to do so.

It was particularly this class, a mix of wealthy professionals, capitalists, and elite students, who were involved in the U.S. backed coup attempt against Chávez in 2002. It is not particularly surprising that the same class dynamic is evident in the 2014 protests. This exodus of the rich and their hostility to the Chávez-Maduro government stems quite clearly from the challenge that the government represents to the power and privilege of such elites. The U.S. ruling class and policymakers despise the Venezuelan government not only for its policy of “re-nationalization” of the country’s oil, but also because it provides model of independence and autonomy for the global south. In this way, the interests and prerogatives of both the expatriate Venezuelan community and U.S. imperialism converge.

- The threat that the Venezuelan government poses, both to the power of the Venezuelan ruling class and U.S. hegemony, is transparent. A few important economic indicators exemplify this. For instance, from 1997 to 2011 the share of wealth of the poorest 20% has increased from 4.1 to 5.7%, a modest advance. Meanwhile, the wealth of the richest 20% has decreased from 53.6 to 44.8% during the same period. The GINI coefficient, which measures wealth inequality (the lower the number the more equal, the higher the number the more unequal), has decreased from 48.8 in 1996 to 39.02 in 2011, making Venezuela one of the most equitable countries in South America. ((Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Venezuela).)) The logical question to ask is how this redistribution of wealth is being put to use. In terms of impact on poverty levels, education, and access to basic medical care and services, there is no doubt that redistribution has had an immensely positive impact on the lives of millions of Venezuelans.

-

Amount of people living in poverty: ((Embassy of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela to the United States.))

1997 – 54.5%

2005 – 43.7%

2011 – 33.2%

Percentage of people living in extreme poverty:

2003 – 29.8%

2006 – 12.5%

2011 – 6.8%

Households in poverty:

1997 – 48.1%

2005 – 37.9%

2011 – 21.2%

Unemployment:

2003 – 16.8%

2009 – 7.5%

Total net enrollment ratio in primary education for both sexes:

1999 – 87%

2009 – 93.9%

Primary completion rate for both sexes:

1991 – 80.8%

2009 – 95.1%

Infant mortality rates:

1990 – 28 per 1,000

2010 – 16 per 1,000

Percentage of the population with sustainable access to drinking water:

1990 – 68%

2007 – 92%

Likewise, since 2002 the free government program Misión Robinson has taught more than 2.3 million people how to read and write. ((Edward Ellis, “Venezuela Celebrates Five Years Free of Illiteracy.”)) In 2007, the literacy rate for 15-24 year olds of box sexes was above 98%. Due to programs such as the National Technological Literacy Plan, which provides free software and computers to schools, 35.63% of Venezuelans were Internet users by 2010.

It seems transparent, then, that the thrust of these demonstrations are the product of Venezuela’s ruling class, who stand diametrically opposed to the tinkering with their wealth and power, let alone a fundamental restructuring of Venezuelan society. The rich and the upper middle class are attempting to reassert themselves, as they attempted to do in 2002 and on a smaller scale many times thereafter, against a government which is working for the immediate needs of the poor and the working class. What has become increasingly apparent is that while the hegemony of the ruling class inside Venezuela has broken down over the past decade, on campuses and universities inside the United States, where the sons and daughters of wealthy expatriates have enrolled, it is those with privilege and power who dictate the narrative.

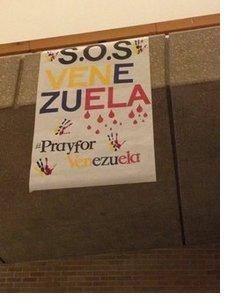

While I cannot speak to campuses and Latino student organizations all across the United States, and I make no claim that my anecdotal evidence is fully representative, my experience with the Latino Student Union (LSU) and South American and Hispanic Students’ Association (SAHSA) at the University of Toledo (UT) seems to be suggestive of the overarching trajectory. At UT, a very working class university, one can walk through the student union and observe the large “S.O.S. Venezuela” and “#PrayForVenezuela” banner draped over the railings above the densely populated Starbucks below it. The banner shows red droplets, presumably blood, dripping from the letters, alluding to the myth that the Venezuelan protests have been drowned in violence.

While I cannot speak to campuses and Latino student organizations all across the United States, and I make no claim that my anecdotal evidence is fully representative, my experience with the Latino Student Union (LSU) and South American and Hispanic Students’ Association (SAHSA) at the University of Toledo (UT) seems to be suggestive of the overarching trajectory. At UT, a very working class university, one can walk through the student union and observe the large “S.O.S. Venezuela” and “#PrayForVenezuela” banner draped over the railings above the densely populated Starbucks below it. The banner shows red droplets, presumably blood, dripping from the letters, alluding to the myth that the Venezuelan protests have been drowned in violence.

The narrative encapsulated by the banner, hung by the SAHSA, has been regurgitated almost verbatim and without challenge by the leadership of the LSU. Thus, one finds their Facebook page littered with commentaries propagating the narrative of the rich. One e-board member implored fellow LSU members to “support our SAHSA familia by spreading awareness of the tragedies in Venezuela.” One member, a business student in the business fraternity, shared the “What’s going on in Venezuela” propaganda video on YouTube with the attached message: “Everyone should know the truth! My Venezuelan friend posted this to share with the world, please take 6 minutes to show love to our South American neighbors in this troubled time.” A Venezuelan student, showing the close proximity with which LSU and SAHSA work, explained that “Us Venezuelans are not that many here in UT! and thats why we need all of your support!!! Share all the information you can about venezuela, videos, pictures, etc. Keep us in your prayers, and we will let you know about our next move!” One member emphatically declared “ABAJO MADURO, ABAJO SOCIALISMO VIVA LIBERTAD Y JUSTICIA.”

In sharp contrast, when a former member of the LSU attempted to engage in the discussion by presenting a more nuanced view of what was happening, she was quickly hounded by the Venezuelan opposition and their supporters. In response, I adumbrated the arguments that have been reiterated here, presenting a counter-narrative to the one that SAHSA and LSU has dutifully echoed. Within minutes, my commentary was deleted. When I inquired as to why it was deleted, I was subsequently blocked from the organization’s page. All of the anti-Maduro comments remain on the page, a testimony to the ideological pluralism and commitment to divergent narratives that one could expect from an organization criticizing the purported “lack of free speech” in Venezuela.

In this strange twist of fate Latino student organizations such as the LSU, established at UT in 1972 and originally juxtaposed with the imperatives of power and imperialism, have in fact become subservient to the very powers many of the founders sought to challenge. Campus-based Latino student organizations were often birthed in the tempest of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the New Left, and for our purposes the Latino segment of this movement in particular, was radically challenging the dominant structures of society. This crucible of struggle produced the burgeoning Chicano movement, as well as revolutionary organizations like the Puerto Rican Young Lords, modeled on the Black Panther Party (BPP), which presented a new revolutionary discourse of emancipation, liberation, and solidarity with oppressed peoples. Although not every Latino or cultural student organization was as radical, the language and ideas infused and permeated the development of such organizations. Even as late as 1985, in the height of the anti-apartheid struggle, Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the BPP, gave a talk at the University of Toledo, suggesting that the “structure to start to build a national organization of freedom” could be located in the Black Student Unions. In essence, culturally-based organizations such as the BSUs and LSUs still maintained their radical political dimensions as late as the mid-1980s.

Four decades later, in 2014, these same student organizations were now parroting the propaganda of corporate media outlets, slandering a radical government which has defied U.S. imperialism in the region and dramatically improved the lives of the masses. In his work Youth, Identity, and Power: The Chicano Movement, Carlos Muñoz explains the process by which this transition occurred: “Student protest gave birth to student movements, which developed a counter-hegemonic process to challenge the dominant ideology and the institutions through which it permeates society. But this counter-hegemonic process was eventually undermined by the strategies of repression and cooptation on the part of those who ruled those institutions.” ((Carlos Muñoz, Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement (Verso, 2007), 14.)) As Muñoz explains, while some of the white student organizations such as SDS and the Free Speech movement were rooted in the “white middle-class,” this was “not true of the Chicano and Black student movements.” ((Muñoz, 13.)) The Chicano youth movement, for instance, reflected “characteristics related to the nature of racial and class oppression experienced by the Mexican American working class.” ((Muñoz, 15.)) There is no clearer example of how the “counter-hegemonic process was eventually undermined” than by observing the LSU leadership’s unwavering position on Venezuela. Over forty years of shifting campus terrain, the imposition of enormous debt on students, increasing atominization and depoliticization, and the influx of wealthy expatriates into universities has transfigured the character of cultural student organizations. Now, instead of expressing solidarity and commitment to the struggles of a government targeted by U.S. imperialism for advancing working class interests, student organizations such as the UT LSU are willful mouthpieces for the most privileged, most elite segments of societies like Venezuela.

It remains to be seen whether radical, class-conscious students opposed to imperialism can reposition themselves as student leaders in place of the vacuous, servile representatives of privilege and power that now occupy such spaces at institutions like the University of Toledo. One can only hope that the UT LSU and similar organizations rekindle the radical spirit that once animated them.