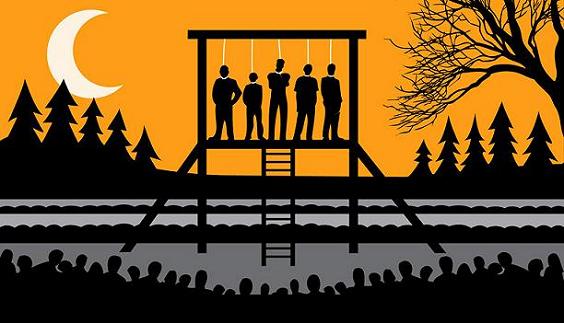

In October 1864 the Colony of British Columbia martyred five “Chilcotin Chiefs.” One hour before sunrise on October 26, with a crowd of 250 gathered to pay witness, the Crown hung these defenders of the Indigenous laws on a scaffold provocatively placed in a native graveyard. This event remains one of the most dramatic moments in the history of Canada’s relationship with the Indigenous Peoples.

October 26 is now a national day of remembrance for the Tsilhqot’in People. This year’s formal ceremony will be held at Puntzi Lake, near a key site in the events leading toward the martyrdom. How is Puntzi Lake connected to the eventual hanging of “The Chilcotin Chiefs?”

After Europeans discovered gold in the Cariboo mountains in late 1860, they began searching for the quickest route to the new mines. All the most direct routes passed through Tsilhqot’in territory. Yet the Colonial Government under James Douglas made no official contact with the Tsilhqot’in to seek consent, to make treaties or to offer payments for easements and the like. Indeed, the Colonial official charged with native relations and land issues seems to have declined to attend a council meeting with leaders from both the East and West Tsilhqot’in, from Klus Kus and from other Southern Dakelh communities affected by these developments within the settler community.

Several private parties did contact various Tsilhqot’in communities in summer 1861. Eventually these communities approved two routes across Tsilhqot’in territory to the mines, and eventually beyond to connect with Canada. These two roads would have joined together just west of Puntzi and then continued along the Lake’s north side toward the Fraser River. So began the Tsilhqot’in experiment with engaging European settlers, especially Canadians. And it all began at this site.

Anticipating these roads, a settler partnership with strong ties to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s colonization and settlement arm selected a strategic location beside a creek at Puntzi for a roadhouse and farm. Something like a combined motel, restaurant and gas station, roadhouses provided services for travellers and their horses.

When the partners arrived onsite at Puntzi in spring 1862, they had to confront the reality (which was undoubtedly known to them from scouting trips made the previous summer) that their desired location by the creek had been long-occupied by a Tsilhqot’in family. A family at that time headed by a man known in the written record as Tahpit.

These three partners were the first settler/immigrants to arrive in Tsilhqot’in territory under the colonization movement begun elsewhere on the Pacific Shelf in 1858. They were: Alex McDonald, a Canadian from Glengarry County (in what is now Ontario) who already had lived in the Interior for several years and who was the leading figure in all the activity at Puntzi; Peter McDougall of Ottawa, who was well-connected within the HBC’s Pacific disrtricts; and a Englishman, William Manning. Manning had arrived in the Interior two years before with McDonald’s former partner from the California gold rush, Major Downie, while exploring for an inland route along the Skeena River.

To secure some form of traditional usage rights, the partners arranged for Manning, who was to be the development’s resident manager, to marry the daughter (Nancy) of the regional leader in the traditional way for forging alliances. This leader actually had died during the winter of 1861/62 and his son, Alexis, (Nancy’s brother) was then taking his place. As it happened, Manning already had a wife and two daughters in England. As Dr. Helmcken would later note, the savage desire for windfall profits through land speculating in.B.C. easily warped all Christian scruples.

To secure new rights under the proposed colonial system, whose jurisdiction they expected the Governor one day would extend to Tsilhqot’in territory, the partners marked “all the land around” to claim under the Pre-Emption Act. Yet, to enjoy the rights of occupation implied in the fee simple title they then expected to receive, they first would have to see the Tsilhqot’in family living on the land removed so the land could be considered unoccupied. Colonial land legislation made the Indigenous Peoples trespassers on their own land.

According to notes made by Judge Begbie, in spring 1862, before there were any other settlers in Tsilhqot’in Territory, these settlers threatened to introduce smallpox as a punishment if the Puntzi Tsilhqot’in did not allow them to enjoy quiet possession of this land. Then, in June 1862, smallpox actually did appear at Puntzi. By September an eye-witnesses reported seeing “500 graves.” The Tsilhqot’in tradition is that only two of those then in residence at Puntzi survived.

A full discussion of how parties led by J.B. Pearson (an intimate of the McDonald family) and Francis Poole spread smallpox in Tsilhqot’in territory during June of 1862 can be found in The True Story of Canada’s ‘War’ of Extermination on the Pacific. It is the Tsilhqot’in tradition (confirmed in the book beyond a reasonable doubt from sources in the written record) and that of many other B.C. First Nations that the settler community deliberately spread smallpox in 1862 in an ethnic cleansing exercise designed to deprive the Indigenous Peoples of their resources and to weaken their ability to maintain political control of their territories.

In 1865 a Tsilhqot’in eye-witnesses said in a sworn affidavit that, based on evidence available to them, the Tsilhqot’in had convicted Alex McDonald of mass murder by introducing smallpox at Puntzi. Consistent with this, the record shows that McDonald was present at Bella Coola when the Pearson and Poole parties arrived there in 1862. And, therefore, he was available to guide them to Puntzi on a mission of introducing smallpox to benefit the partner’s land claim…just as the settlers had said they would and just as the Tsilhqot’in say they did.

In late May 1864, a Tsilhqot’in party, led by “The Head War Leader” Lhatsassin, executed McDonald and McDougall for their role in the introduction of smallpox, especially at Puntzi. The resident manager of the Puntzi roadhouse, Manning, had already been executed in early May at this Puntzi site.

None of these settlers was taken by surprise. The evidence is that they had the benefit of due process and justice under Tsilhqot’in law. Notes made by Judge Begbie, based on the testimony of eye-witnesses or participants in Manning’s execution, show Manning was notified of his danger early in the day. He was advised to choose exile or to avail himself of the appeal process by seeking sanctuary from the appropriate area leader, Alexis. Manning refused these options, apparently believing the Tsilhqot’in were bluffing.

After a day spent at the Puntzi lodge (about three kilometers from this site) debating the appropriate action, the community delegated Tahpit to execute Manning. The record seems clear that he was reluctant to do so. However, as the party most aggrieved by the settlers extorting his family’s home, it seems to have been agreed that executing Manning was most appropriately both his private and public duty. After Manning’s execution, the Tsilhqot’in burned the Puntzi roadhouse.

For properly performing this duty under Tsilhqot’in law, the law of the land long in effect at all the relevant times and places, British Columbia subsequently convicted Tahpit of murder in a show trial. In that trial the Tsilhqot’in were denied due process under British law. Tahpit then became one of the “Chilcotin Chiefs” hung Oct. 26, 1864.

Also hung that day were Lhatsassin and his son, Biyil, for executing McDonald under Tsilhqot’in law. In July 1865, another leader, Ahan or Kwutan, was hung for executing Peter McDougall.

These four Tsilhqot’in, then, were hung by the Crown because they had executed settlers who had spread smallpox. Yet, in so doing, they had only carried out a policing function while properly authorized to do so by the appropriate political authority: the Tsilhqot’in People as the sovereign power in their territory. In contrast, the Colony had no legitimate political authority for its killings.

In addition to managing the use of violence to police abhorrent behaviour within its sovereign jurisdiction, every community also occasionally relies on violence in the form of war to protect itself from those who would overthrow the legitimate sovereign by unlawful means.

Two other “Chilcotin Chiefs” Chaysus and Telloot, were hung by the Colony Oct. 26, 1864 for their participation in a properly undertaken act of war to prevent the introduction of smallpox at Bute Inlet, another part of the ethnic cleansing program by the settler community to displace the legitimate sovereign power.

What took place here at Puntzi, then, was the very beginning of the Colonial experience as it has been endured by the Tsilhqot’in people for 151 years, While the martyrdom of “The Chilcotin Chiefs” was a most dramatic moment within this experience, it was not the climax. The genocide begun at Puntzi was continued with a paramilitary occupation that saw natives confined to reserves too small to sustain their populations, deprived of their children in residential schools and otherwise denied political control of their lives and resources.

This genocide continues today with the minimization or denial of this experience within the educational system, including at Canadian universities, with the disposition and despoiling of Tsilhqot’in resources without the People’s consent, and with the Canadian government’s argument about to be heard at the Supreme Court of Canada that the aboriginal rights nominally confirmed in Canada’s constitution do not extend to whole indigenous territories.

It is a circumstance of cruel irony that Canada now wants to limit claims by the indigenous population of British Columbia primarily only to sites still occupied after 90 percent of the population had been killed by the purposeful actions of the settler community, or the Crown and its agents. This site at Puntzi was unquestionably occupied by the Tsilhqot’in People before 1862. Yet the Canadian government would head its law and policy down a path which will deny the Tsilhqot’in both access to the site or reparations for its deprivation. Equity and reconciliation between Canadians and the Indigenous Peoples cannot be achieved along this route while it depends on denial of the underlying genocidal truth.

The remembrance day ceremony at Puntzi, or the spirit of the day for those who cannot attend in person, is open to everyone who may wish to spend a few moments reflecting on the ongoing tragedy of all these circumstances.