Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan wrote another excellent academic paper, Can Capitalists Afford Recovery?:

Economic, financial and social commentators from all directions and persuasion are obsessed with the prospect of recovery. The world remains mired in a deep, prolonged crisis, and the key question seems to be how to get out of it. The purpose of our paper is to ask a very different question that few if any seem concerned with: can capitalists afford recovery in the first place?

This question does not come out of the blue. Over the past several years, we have published a series of papers on the crisis (Bichler and Nitzan 2008, 2009; Nitzan and Bichler 2009b; Bichler and Nitzan 2010; Kliman, Bichler, and Nitzan 2011). Our basic argument in these papers is that this is a systemic crisis and that capitalists have been struck by systemic fear: fear for the very survival of the system.

This fear, we have further argued, is objectively grounded. Our reasons, though, are very different from those given by heterodox political economists, particularly Marxists. Whereas for the Marxists, the crisis is the symptom and culmination of weakening accumulation, for us it is the consequence of its unprecedented strength.

The two views are anchored in very different cosmologies (Bichler and Nitzan 2012b). Liberals and Marxists see capital as an economic entity and capitalism as a mode of production and consumption, so for them the accumulation crisis is anchored in the economics of production and consumption. By contrast, we see capital as a symbolic representation of power and capitalism as a mode of power, so for us, the crisis of accumulation is a crisis of capitalized power.

According to our research, the accumulation of capital-read-power might be approaching its asymptotes, or limits (Bichler and Nitzan 2012a). The closer capitalized power is to its asymptotes, the more difficult it is to augment it further. Capitalists, though, have no choice. They are conditioned and compelled to increase their capitalized power without end, and that relentless drive breeds conflict. It forces capitalists to increase their threats, escalate their sabotage and intensify their use of force – and this intensification is in turn bound to trigger stronger resistance, contestations, uprisings and more.

By the early 2000s, capitalists began to realize the unfolding of this asymptotic scenario. They started to sense that their power is nearing its limits and that accumulation is becoming ever more difficult to achieve and might be reversed. And given that capitalization is forward-looking, the result has been a major bear market.

The present paper contextualizes and examines this process from the viewpoint of economic policy. The analysis is divided into three parts. The first part deals with the mainstream macroeconomic perspective. This approach claims to have already solved all the theoretical riddles, so the main emphasis here is on the practical question of how to engineer a recovery. The second part deals with the Marxist view. Marxists stress the inherent contradictions of accumulation, so the question for them is the very possibility of sustained growth. The third and final part takes the view of capital as power. Capitalized power hinges not on growth, but on strategic sabotage. So from this viewpoint, the key question is not how capitalists can achieve and sustain a recovery, but whether they can afford it in the first place.

The paper begins by discussing what capitalists fear the most:

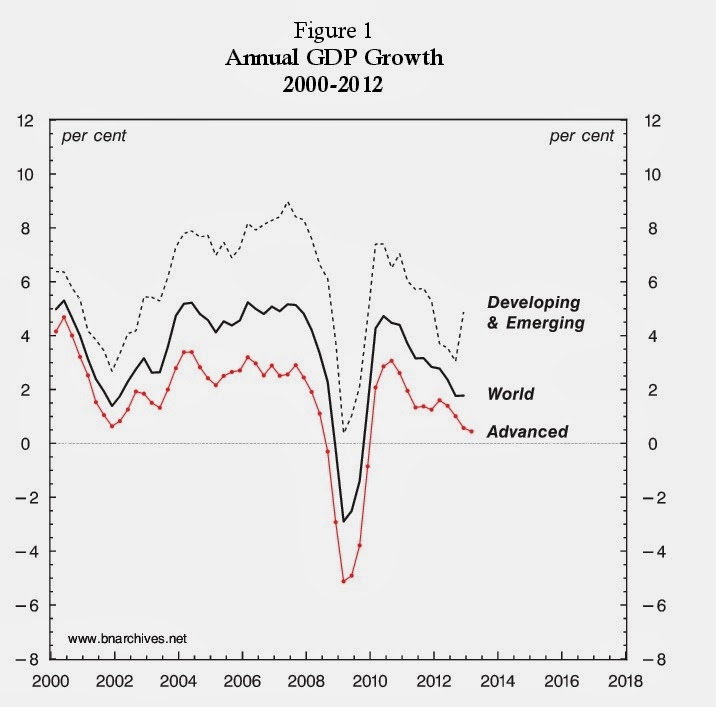

Figure 1 provides the broad context (click on image below). The chart is a snapshot the ‘state of the world economy’ since the beginning of the systemic crisis in the early 2000s. The figure shows three annual GDP growth rates: (1) the dotted red line is for the advanced countries, (2) the dashed line is for the developing world, and (3) the solid line is for the world as a whole. We can see the first downturn in 2000-2002. The developing world and emerging markets recovered briskly from this decline, but the advanced countries showed a very feeble recovery. Then came the 2008-9 drop. This downturn was much [more serious (–5 per cent for the developed world and –3 per cent for the world as a whole). And the recovery was limited and brief. By 2010, both regions – and the world as whole – began to decelerate rapidly.

Policymakers looking at this chart (click on image above) must get the shivers. Despite massive policy intervention – including unorthodox measures that only a few years back would have been considered unthinkable – the world economy remains unresponsive. The developing world shows an uptick; but with the current emerging market turmoil, these data seem ripe for a significant downward revision. In the meantime, the advanced countries are pretty much at a standstill.

I highly recommend you take the time to read the rest of Bichler and Nitzan’s paper. The HTML, PDF and data are all available here. I thank Jonathan for sending me this paper and will share with you an exchange we had concerning their findings.

First, a side note. Jonathan Nitzan used to work as BCA Research as an Associate Editor in the Emerging Markets group. Unlike most academics, he knows how financial markets actually work and has a deep understanding of the distribution of power which shapes our society. Together with Shimson Bichler, they published an important book, Capital as Power, which I also highly recommend if you want to gain insights on the deficiencies of Marxist, Keynesian and traditional economic theories on capital and labor (not an easy read but a lot easier than the typical dry, esoteric academic gibberish).

Jonathan sent me their latest paper and asked me to comment. I share our exchange below:

Leo Kolivakis: I liked your paper a lot but had a few questions and concerns. One was at what point does inequality hurt capitalists? Your analysis does not cover this. Also, pensions and sovereign wealth funds are acting to counteract capitalist excesses. What are your thoughts on this?

Jonathan Nitzan: 1. “At what point does inequality hurt capitalists?” As far as inequality is concerned, the answer is “at no point”. The higher the inequality, the better off the capitalists. This answer sounds definitive because, in our view, inequality is the very purpose, the end goal that capitalists — including sovereign funds and pensions — are conditioned and compelled to achieve. Capitalists are driven to beat the average, and beating the average means higher inequality, by definition. The real question for capitalists is not how much inequality can they “sustain” (100% as far they are concerned), but the consequences of inequality to the stability of their regime.

2. The impact of inequality on instability comes in two ways. In the short run, the strategic sabotage necessary to raise inequality also raises risk and therefore lowers capitalization. In the long run, it may destabilize the entire regime.

3. The figure below is taken from page 238 of our book Capital as Power (2009). The graph shows the connection between the capital share of income on the vertical axis and unemployment (inverted) on the horizontal axis. This figure is the same as Figure 16 in our paper, with three small differences: (1) unemployment is inverted; (2) unemployment is not lagged; and (3) the data begin in 1933. The figure shows a nonlinear relationship. For capitalists, the ideal level of strategic sabotage is when unemployment is about 7%. This level of unemployment generates the highest capitalist share of income, which is perhaps why economists treat it as the “natural rate of unemployment” and behave as it represents “business as usual”. When unemployment is lower — as it was during the Great Depression or during WWII — the capitalist share of income tends be much lower. Too much or too little sabotage are no good. The Goldilocks level of sabotage is 7% unemployment.

LK: I have a tough time accepting your premise that capitalists can sustain 100% inequality as the consequences to their regime will be devastating. Put simply, whether they like it or not, there are limits to gross inequality and they know it. Whether or not they care is another story but I think they care because gross inequality impacts their quality of life.

As far as pensions and sovereign wealth funds, they are enriching the financial elite but they are also putting pressure on them to lower fees and perform. The power that pensions exercise is enormous and hedge funds and private equity funds need them for assets and the pensions need the latter to obtain their actuarial target return. It’s a complicated relationship, a fragile but symbiotic one.

JN: I think we are talking about the same thing, although perhaps with different emphases.

1. To reiterate our claims, the goal of capitalists is differential and therefore redistributional. By seeking to beat the average, capitalists seek to make income and assert ownership more unequal, by definition. Based on this logic, the ultimate goal of capitalists is greater inequality, and the more the better. That is their built-in goal, a goal over which they have no control. Now, distributional goals are inherently conflictual (what is mine cannot be yours). And to win in conflict capitalists need to inflict sabotage (such as unemployment, incarceration, etc.). Sabotage, however, creates resistance, and this is where we seem to agree: capitalists cannot inflict ever greater sabotage on the underlying population; as you correctly point out, the consequences for the regime will be “devastating”. This is why we claim that capitalists, at least in the U.S., may be approaching the limits, or asymptotes, of their power.

2. Regarding pension and sovereign wealth funds, I’m not sure how their existence and actions alter the process I describe in (1). You say that these funds demand that the “financial” elite performs (by keeping fees low, etc.). That may be true, but it is irrelevant to my point. We are not talking about the “financial” elite; we are talking about the overall income share of capital or of the 1%. Pension and sovereign wealth funds are like all investors. They demand that the companies they invest in “outperform” — that is, that they beat the average and redistribute income in their favour. And since this redistribution requires sabotage, so we are back to square one. If you look at Figures 11, 15-16, you can see that, despite the rise of pension and sovereign wealth funds, inequality is at or approaching record levels.

3. Capitalists are therefore torn between the imperative of achieving further redistribution-through-sabotage and the growing risk that this process creates for their regime.

LK: Not sure about your redistribution argument. If we enhance the Canada Pension Plan for all, the rich will get richer but so will the working poor. I have to think about your arguments very carefully, not as black and white in my mind. The rise of pensions and sovereign wealth funds is a game changer. Rich family offices have been permanently displaced. This might actually save capitalism if we create more jobs.

JN: It seems to me that you are conflating “riches” (utility) with distribution (power). You can have higher “real” income for workers with greater inequality. Our argument concerns the latter process.

If enhanced public pensions redistribute income downward, that would be a game changer. But so far that hasn’t happened, not in Canada and certainly not in the U.S. It seems to me that pension and sovereign wealth funds have put the labour aristocracy and governments on the same side of capital. Just as the capitalists, they too are hostage to the conflictual power logic of capitalism. Bill Gross, Warren Buffet and George Soros could speak about the risk of heightened inequality, but their roles compel them to make it grow.

I thank Jonathan Nitzan for sharing his thoughts with me. There is a lot to ponder in their paper and the exchange above. In particular, can capitalists afford a recovery and if not, at what point does their regime crumble and bring about major social upheaval? And are pensions held hostage to the “conflictual power logic of capitalism” and therefore contributing to increasing inequality instead of reducing it?

I hope enhanced public pensions will be a “game changer” in terms of redistributing income downward but Jonathan is right, so far the evidence does not support that the rise in pensions is reducing inequality. In fact, the evidence shows pensions are contributing to higher inequality. As always, if you have any comments, feel free to share them with me (moc.liamgnull@sikaviloKL) and I will add them to this post

Below, Tim Di Muzio and Jonathan Nitzan discuss power from above and from below at the 3rd Annual Forum on Capital as Power: “Capitalizing Power: The Qualities and Quantities of Accumulation” (Jonathan’s presentation begins at minute 24). A new video on their latest paper will be available in the coming weeks.