There must be more than coincidence to the observation that the American media’s appraisal of a world leader often reflects the State Department’s attitude towards the same leader. Just search history; leaders who failed their people but accepted United States foreign policies received only mild criticisms, while leaders who contended U.S. foreign policies, regardless of relations with their populations, received scathing reviews from popular news sources.

China’s Chang Kai-Shek, Korea’s Syngman Rhee, Vietnam’s President Van Thieu, Nicaragua’s Somoza and in more recent times, Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, Mexico’s Carlos Salinas de Gortari, Russia’s Boris Yeltsin, and Georgia’s Mikheil Saakashvili fit the former pattern. These friends of Washington received relatively harmless rebukes for nefarious actions.

Soviet leaders until Mikhail Gorbachev, France’s Charles de Gaulle, Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, Indonesia’s Sukarno, Cuba’s Fidel Castro, and Venezuela’s Hugo Rafael Chavez, all of whom confronted American foreign policies, were, regardless of their acomplishments, constantly castigated by the American media.

Description of the castigated grows, graduating from being against American policies to being anti-American, then a serious threat to America and finally a danger to everyone. Nothing good can be said about them; anyone muttering kindly remarks is considered ignorant and slightly warped. After the aversion to the anti-Americans who are a danger to everyone engulfs a large percentage of the population, the media joins the bandwagon, aware it best not contradict the one-sided appraisals.

This conditioning enables U.S. foreign policy planners to gain public support for their rejection of foreign critics and for policies that disturb their critics. Initiation of wars in Vietnam, Iraq, Granada, Panama and other countries could not occur before a mention of the name of the leaders of the antagonist nations had aroused an angry emotional reaction in America’s psyche. Economic warfare against several nations could not be practiced until Americans were made to feel that the economic warfare was morally correct; a necessary action to defeat and replace the criminal leader of the impudent nation.

Despite Hillary Clinton having pressed the reset button, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin clearly broadcasts his disfavor with State Department initiatives. Has he also fallen into the Washington character crusher and being leveled due to his alleged antagonism towards America? American media’s scornful attacks on the Russian premier hint at that possibility.

The Russian Prime Minister is continually presented as a bad boy, a tyrannical, and corrupt megolomaniac who assists his cronies in pilfering Russia’s resources. Lacking is a body of verified evidence to support the allegations. Putin’s critics found an opportunity to provide evidence in the recent legislative elections in Russia and promptly accused the Russian premier of personally stealing the election, labeled him rejected by the Russian people, made him responsible for his Party’s losses, and described him as lucky. To them, Russia’s tremendous growth during Putin’s tenure is only due to high energy prices and not his leadership.

Constant repetition of these charges condition the portrait of Vladimir Putin. Are the charges true, specious, or a matter of perspective? If the facts are obscure, logic overcomes the obscurity.

Putin stole the election

The New York Times echoed the American media approach to the confusing situation.

The United States needs Russia’s cooperation on a host of issues, most notably Iran, and the Obama administration made the right decision to try to ‘reset’ the relationship. But that can’t mean giving Mr. Putin’s authoritarian ways a pass. So it was good to hear Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton express ‘serious concerns’ that the voting was neither free nor fair. ((“Not What Mr. Putin Planned,” New York Times, December 7, 2011.))

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) monitored the election and presented an analysis on “free and fair” in a press release.

MOSCOW, 5 December 2011 “Despite the lack of a level playing field during the Russian State Duma elections, voters took advantage of their right to express their choice.

“The observers noted that the preparations for the elections were technically well-administered across a vast territory, but were marked by a convergence of the state and the governing party, limited political competition and a lack of fairness.Although seven political parties ran, the prior denial of registration to certain parties had narrowed political competition. The contest was also slanted in favour of the ruling party: the election administration lacked independence, most media were partial and state authorities interfered unduly at different levels. The observers also noted that the legal framework had been improved in some respects and televised debates for all parties provided one level platform for contestants.

On election day, voting was well organized overall, but the quality of the process deteriorated considerably during the count, which was characterized by frequent procedural violations and instances of apparent manipulations, including serious indications of ballot box stuffing.

Granted the OSCE press release is only a preliminary and abbreviated summary before a final report, scheduled for its 2012 meeting. Nevertheless, its evaluation uses vague expressions — procedural violations, instances of apparent, serious indications — that don’t confirm extensive fraud.

All seven registered political parties were approved to participate in the elections. Is that a narrow field? The Party with the lowest total received only 0.3% of the vote. Did the electorate need more or want more?

Incumbent legislators, certainly those in the U.S., usually have great advantages in elections, monopolize the news and gain more media coverage. Wherever possible, the Party in power slants the election with all its power. What else is new? Proven charges of ballot stuffing and multiple voting demand investigations, but these skewing of elections are minor when compared to the disguised frauds from PACs and lobbies, many of whom control media expressions and campaign funding. Political Parties are shaped to skirt the edges of legality and do everything to assure victory. When the numerical and financial disparity between one political Party and the others is great, as it is between United Russia and its competitors, the favoritism and slant becomes more exaggerated.

By sensationalizing the alleged frauds, constantly repeating and continually re-circulating the same, the media made it difficult to gauge their actual significance. Signals were filtered out and noise amplified so that only the noise was heard. A similar happening occurred with the heavily publicized and videos. Subjectively interpreted, lacking verification and possibly being staged, an unlikely situation, but still a possibility that nobody considered to investigate, an appraisal of the condemning videos places them as images of fraud that look good on Court TV but might be insufficiently convincing for judicial courts. Undoubtedly there were severe irregularities, but were they substantiated as massive and organized or were they more driven by local exuberances and incompetent behaviors?

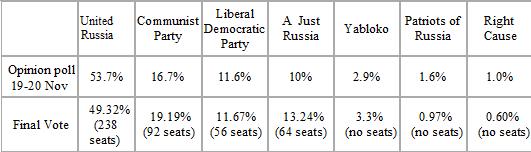

The table below contains significant details for resolving the debate on election validity. It shows that the election results were close to the trend in the polls and to their final readings. If United Russia (UR) did much better than the polls, then fraud would be a definite probability. By doing worse than predicted, either the UR poorly prepared the mechanisms for illegally augmenting vote totals, or the mechanisms did not exist.

The Russian people rejected Putin

The youthful, Internet-savvy Russians who have turned out in the streets in historic numbers in recent weeks want to end Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s untrammeled rule over their country, but whether they can translate their frustration to the political arena – or even whether they will remain fired up — remains an open question. ((Washington Post, December 19, 2011.))

Did voters, who were electing local delegates to the Duma, go to the polls thinking of Prime Minister Vladimir Putin? Unlikely. Interim elections reflect voter opinions on the legislature and somewhat on the president, who is Dmitry Medvedev. In Russia, as in France, the president has considerable power. He nominates the highest state officials, including the prime minister, can pass decrees without consent from the Duma, and is head of the armed forces and Security Council.

The American media might insist that Putin manages everything behind the scenes, but President Medvedev’s performance during the last four years contradicts that assertion. No question that several years ago Putin dealed with Medvedev and promised him support for the presidency in return for a promise that Medvedev would not run for a second term. Knowledge of that agreement might have disturbed voters and swayed their preferences. Nevertheless, Medvedev has operated sufficiently independent during his reign. U.S. media portrays Putin as the Russian leader. Putin is prime minister, but Russians and the U.S. State Department interacted with President Medvedev during the last four years.

Putin’s United Russia was Defeated

“It’s embarrassing enough to do poorly in an honest election. Putin’s party managed to crater despite vigorous measures to rig the vote.” ((Chicago Tribune, Steve Chapman, Dec. 15, 2011.))

Crater? A defeat? Steve Chapman misrepresented the election. Gaining 49.3% of the vote in a five Party system is an astonishing victory, not as large as previous United Russia victories, but a total that any European political Party would envy. In the last national elections in United Kingdom, France and Germany, no political Party received more than 36% of the vote. Don’t weep for UR. They are not too sad.

The electorate normally anguishes when the same political Party dominates its life for a decade. Lower totals for United Russia reflect that usual discontent. After ten years of power, it is surprising that Russia’s leading political organization still retains 50% support from the electorate. Evidently, the populace has not tired of United Russia’s managed economy, which features statist and nationalist positions, both of which have irked the western powers. The statist Communist Party and nationalist Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (misnamed) showed increased vote totals from their 2007 vote totals.

Putin was lucky. Yeltsin was unlucky.

“In retrospect, Mr. Putin was lucky to inherit a recovering economy and an incipient oil- and commodity-price boom from Mr. Yeltsin.” ((The Economist, February 28, 2008.))

The difference in media treatment between Boris Yeltsin’s government, which brought Russia to poverty and Vladimir Putin’s Russia, which brought Russia to a moderate prosperity, proves the thrust of this article: “There must be more than coincidence to the observation that the media’s appraisal of a world leader, which often shapes public opinion, reflects the State Department’s attitude towards the same leader.”

Putin’s Russia has its corrupt and authoritative components. Unfortunately these are common features of a nation where corruption is ingrained into the society, and authoritarian rule has been the norm.

Evgeny Yakovlev and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya, “State Capture: From Yeltsin to Putin,” explained the situation.

In contrast to Yeltsin whose political term was notorious for creating and strengthening oligarchs, Putin began his first term in the office by fighting the most famous of them: Berezovsky, Khodorkovsky, Gusinsky, and Lebedev. Fighting oligarchs was again high on the agenda during his second election campaign. In addition, Putin attempted centralization process, restricting autonomy of regional political elites and moved political and economic power from the regions to the federal center6. A new tax law, which restricted the use of individual tax breaks, was adopted, as well as a number of laws, aimed at easing the burden of business regulation. A new anti-corruption campaign was launched and some governors who were considered most corrupt, e.g. Rutskoy in Kursk region and Nazdratenko in Primorsky region, were not permitted to run for re-election. The governor of Yaroslavl region, Lisitsin, was under a criminal investigation in early fall of 2004 because of pursuing illegal paternalistic policies towards regional business.

The following graphs show the differences in operation beween “democratic” Yeltsin and “authoritative” Putin.

Note that Saudi Arabian and Iranian oil productions increased during the 1990’s and Russian oil production dropped sharply. Demand was there, but Yeltsin’s policies neither enabled the world’s largest oil producer to produce nor prevented it from halving output within two years. Although oil production and prices bottomed, Yeltsin’s Russia did not. The GDP continued to fall, lowering to 38% of the value at the time Yeltsin took office.

Regard Putin’s administration. Oil production increased rapidly from the day he took office, up 50% in eight years. GDP increased more rapidly than oil production and prices, rising monotonically to an increase of 700% (in nominal terms) in the same eight years. In July 1997, opinion polls showed Yeltsin having about 5 percent of public support. Putin, who once had 70% approval, has been constantly castigated by the American media. Yeltsin, who fell to 5% approval, received mild rebukes.

Was Yeltsin, who created his own problems, unlucky? Was Putin, whose administration knew what to do, just lucky?

Those who continue with the crushing of Vladimir Putin are tending to bring back the era of Yeltsin and the oligarchs, a time when Russia was a paradise for five to ten persons and a weak antagonist to U.S. military adventures.