Lose all your troubles, kick up some sand

And follow me, buddy, to the Promised Land.

I’m here to tell you, and I wouldn’t lie,

You’ll wear ten-dollar shoes and eat rainbow pie.— “The Sugar Dumpling Line,” American hobo song

“Today, almost nobody in the social sciences seems willing to touch the subject of America’s large white underclass,” writes Joe Bageant on page 2 of his second book, Rainbow Pie.

So what’s this self-professed and proud-of-it “redneck” do? This memoirist combination John Steinbeck, Michael Harrington, Henry Thoreau–with a funny bone to wallop your gut—what’s he do but produce the best book on the unsung 60 million (cozened to vote against their own self-interest, fodder for corporations’ wars)—write the best book on them that anyone of his generation has written!

Bageant knows the territory like the back of his ham hocks. Now a frequent guest on NPR and the BBC, Bageant has had his journalism and commentary in periodicals and at websites around the world (check out www.joebageant.com for a compilation). His first book, Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches from America’s Class War, announced to the literate world: here’s a thinking writer who can make you cry with the tenderness of his character depictions of the real folk, and make you livid as he shows how their “operative community democracy” was sliced and diced by corrupt media, religious charlatans, and, yeah, the military-industrial complex.

Deer Hunting is an excellent book. Rainbow Pie is even better. Rainbow Pie is about now; Deer Hunting laid the groundwork, sowed seeds of memory for this West Virginia-born sui generis intellectual. Rainbow Pie brings those seeds to fruition amidst our present devastation—the “financialization” of the “transactional economy.” Translation: outsourced jobs; debt and desperation in the homeland.

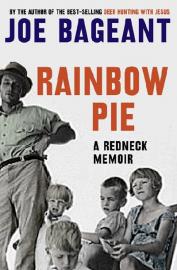

Rainbow Pie: A Redneck Memoir

By Joe Bageant

Scribe Publications, Melbourne, 2010

(U.S. edition, 2011)

September 2010

Paperback: 310 pages

ISBN: 9781921640629

Now mid-60ish, Bageant’s witnessing is astute and acute; he’s been there. “When World War II began,” he writes, “44 percent of Americans were rural, and over half of them farmed for a living. By 1970, only 5 percent were on farms. Altogether, more than twenty-two million migrated to urban areas during the post-war period.” And they engendered children and grandchildren who swelled their ranks by another 40 million—uneducated rural whites and their descendants who form the foundation of “our permanent white underclass,” outnumbering, btw, the other poor/working poor—the Hispanics, blacks and immigrants.

“Even as the white underclass was accumulating,”Bageant writes, “it was being hidden.” Hidden or ignored in the universities…, and caricatured and cartoonized by the media merchants—Beverly Hillbillies then, King of the Hill now! “The official version of all life and culture in America is written by city people,” Bageant avers.

And avers this: “While all those university professors may have their sociological data and industrial statistics verified and well indexed… they’ve entirely overshot the on-the-ground experience.” It’s there—in that experience that Bageant excels. “I went to a one-room school with a woodstove and an outhouse,” he tells us in the intro to Rainbow Pie. And in that same intro he confesses his nervousness about writing a “damned” memoir. “Angry memoirs weeping over some metaphorical pony the author did not get for Christmas in 1958.” But this homespun poet need not worry about flimflam. He can write lyrically like this:

It happens perhaps once or twice every August: a deep West Virginia sundown drapes the farmhouses and ponds in red light, as if the heat absorbed during the dog days will erupt from the earth to set the fields afire.

And sociologically like this:

In all likelihood, there is no solution for environmental destruction that does not first require a healing of the damage done to the human community. And most of that damage… has been done through work, our jobs, and the world of money. Acknowledging such things about our destructive system requires honesty about what is all around us, and an intellectual conscience. And asking ourselves, ‘Who are we as a people?’

And he reveals truths like these: “Maw and Pap were married in 1917. He was twenty-three; she was seventeen. Pap had walked nine miles each way for over a month to court her. … Their world was mostly just birth-to-death work, and pride in the fact that it was such. ‘My man is sure enough a worker,’ Maw observed.” And, “In symbolization of their union, Pap planted two rose bushes that he fussed over and nurtured until his final days.”

What his parents and their neighbors in his boyhood’s West Virginia, and in the small city in Virginia where he spent his later school years—what they lacked in material goods and sophistication and knowledge about the outside world was more than compensated with a sense of belonging: “Their kind of human-scale family farming proved successful for twelve generations because it was something more—a collective consciousness rooted in the land that pervaded four-fifths of North American history.” And, “Farmers grew more connected in a community network of seasonal mutual efforts, such as threshing, hunting, hog slaughtering, haymaking, clannish marriages, and birth, burial, and worship. Their conventions were still being observed… as I was growing up.”

And that’s the life—the lost life now—that Bageant sings and laments in Rainbow Pie. His art is in the singing of particulars, and how he weaves social, economic and political facts into the warp and weft of stories about salt-of-the-earth characters passing away before our eyes: “For the first time I understood something. I didn’t quite know what, but I knew it had to do with the passing of all things, and that eternity does not care about that passing.”

Bageant’s book is poignant, humorous, peopled with characters who “cast their own shadows”; and, it’s incredibly informative. It’s his way of marshalling hard facts while telling stories about decent, independent-minded people buffeted by economic and social forces they cannot grasp that makes his work so special. About the post-war rural-to-urban migrations he writes: “‘Organizing for war’ had taught industrialists and government agencies the best ways of organizing the American population and its resources toward heavier and more profitable production, both of which lay in worker aggregation and concentration.”

“Eternity” may not care. … But in Bageant’s mighty and tender hands, we do.