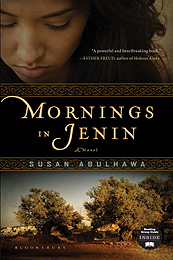

Morning in Jenin, previously titled The Scar of David, by Susan Abulhawa, in its first edition, it is about a scar and a man named David who bears the scar, and another scar — the scar worn by Amal, the protagonist of the story, whom we follow from childhood and who also incurred a scar on her lower abdomen as the result of the exit wound of a rifle bullet from an Israeli soldier who shot her in the back as she walked to her home in the Jenin refugee camp.

Of course, it is also about other scars – the scar of the land:

Now, that ancient village with its walls made of secrets and trees planted in blood, looked inanimate. Around Jerusalem and in the West Bank, settlements on every hilltop – with their manicured green lawns and red roofs metastasizing into the valleys like an earth rash – contrasted cruelty to the crumbling Arab homes where sewage from these settlements drained and where settlers often dumped their garbage.

And it is about the scar that is Zionism itself, with its ethnic cleansing of the indigenous population, an ethnic cleansing that consisted of massacres in about 30 Arab villages, with two to three thousand massacred, and the subsequent bulldozing and destruction of more than 500 such villages. And it is about the scaring of Palestine and of its people. And it is about the scaring of humanity with Zionism’s brutality and of its ongoing destruction – genocide really – of another people’s identity and culture. Israel has trouble accepting that Palestine is the home of the Palestinian people and simultaneously claiming legitimacy for itself, as well it should, as the claims are incompatible.

The author says of the Israelis what she claims the Israelis already know:

… that their history is contrived from the bones and traditions of Palestinians. The Europeans who came knew neither hummus not falafel but later proclaimed them “authentic Jewish cuisine.” They claimed the villas of Qatamon as “old Jewish homes” even though, hard as they tried, they could not duplicate the Arab architecture that arched every which way in the ceilings, staircases, windows, and doors. They had no old photographs or ancient drawings of their ancestry living on the land, loving it, and planting it. They arrived from foreign nations and uncovered coins in Palestine’s earth from the Canaanites, the Romans, the Ottomans, and then sold them as their own “ancient Jewish artifacts.” They came to Jaffa and found oranges the size of watermelons and said, “behold! The Jews are known for their oranges.” But those oranges were the culmination of centuries of Palestinian farmers perfecting the art of citrus-growing.

We follow Amal from childhood as her life intersects the major events of Palestinian history since 1948 and simultaneously we empathize with her suffering in the loss of her ancestral home in the village of Ein Hod and the loss, one by one of the members of her family to Israeli bullets and Israeli aerial bombardments, or in the case of David, her baby brother, his disappearance into the hands of an Israeli soldier who wants him as a gift to his childless wife. We experience Amal’s loss of her mother to insanity resulting from the death of her husband who resisted the advance of the Jewish forces toward their village and the disappearance of her baby boy, to where, she never knows.

We follow Amal from childhood as her life intersects the major events of Palestinian history since 1948 and simultaneously we empathize with her suffering in the loss of her ancestral home in the village of Ein Hod and the loss, one by one of the members of her family to Israeli bullets and Israeli aerial bombardments, or in the case of David, her baby brother, his disappearance into the hands of an Israeli soldier who wants him as a gift to his childless wife. We experience Amal’s loss of her mother to insanity resulting from the death of her husband who resisted the advance of the Jewish forces toward their village and the disappearance of her baby boy, to where, she never knows.

Palestinian history is projected onto to the family of Amal as it is, in reality, projected onto so many Palestinian families.

At what price, Israel? What price does the world pay for Israel’s existence?

Ms Abuldawa takes us through the 1948 expulsion of the Palestinian villagers from Ein Hod as we hide with the child, Amal, underneath her home which is destroyed over her. And we watch the villagers in long lines carrying their life possessions away from their village. Pictures of these processions from 1948 have survived, one is displayed on the cover of Benny Morris’s book, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem. Another on the cover of Ilan Pappe’s book, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. And another, on the cover of Nur Masalha’s book, The Expulsion of the Palestinians.

We may read from historian, Benny Morris (Operation Dani):

About noon on 13 July, Operation Dani HQ informed IDF General Staff/Operations: Lydda police fort has been captured. [The troops] are busy expelling the inhabitants. … Lydda’s inhabitants were forced to walk eastward to the Arab legion lines; many of Ramle’s inhabitants were ferried in trucks or buses. Clogging the roads … tens of thousands of refugees marched, gradually shedding their worldly goods along the way. It was a hot summer day. The Arab chroniclers, such as Sheikh Muhammed Nimr al Khatib, claimed that hundreds of children died in the march, from dehydration and disease. One Israeli witness described the spoor: the refugee column ‘to begin with [jettisoned] utensils and furniture and, in the end, bodies of men, women, and children.

Now in the Jenin refugee camp, she recounts the brief surge of optimism upon reading in the press of the arrival to Palestine of UN mediator, Count Folke Bernadotte, who was sent to Palestine by the Secretary General in order to produce a recommendation as an alternative to the partition resolution with which the UN was then having second thoughts. And days later she read in the same press of his assassination by the Jewish terrorist group, Stern Gang, on the orders of its head, Yitzhak Shamir who later was to become Israel’s Prime Minister. Count Folke Bernadotte had in previous years negotiated the release of 25,000 Jewish prisoners from Nazi concentrations camps in Germany. Murder at the hands of Jewish terrorists was his reward.

The author relates the 1967 War – Israel’s takeover of East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and its further wave of ethnic cleansing, consisting of another 300,000 refugees, and, of her brother, Yousef, she says:

As the conquest in 1948 did for Hasan [her father], Israel’s attack in 1967 and subsequent occupation of the West Bank left his son Yousef with a tentative destiny. The grip of Israeli occupation wrapped around his throat and would not let up. Soldiers ruled their lives arbitrarily. Who could or could not pass was up to them, and not according to any protocol. Who was slapped or not was decided on a whim. Who was forced to strip and who was not – the decision was made on the spot. …

Toughness found fertile soil in the hearts of Palestinians, and the grains of resistance embedded themselves in their skin. Endurance evolved as a hallmark of refugee society. … They learned to celebrate martyrdom. Only martyrdom offered freedom. Martyrdom became the ultimate defiance of Israeli occupation. …

But the heart must grieve. Sometimes pain emerged as joy. Sometimes it was difficult to tell the difference. …

Of the days leading up to the 1982 invasion of Lebanon by Israel, the author tells us that Israel had been striking Lebanon to provoke the PLO into retaliating with Israeli defense minister, Ariel Sharon vowing to wipe out the resistance once and for all, and in July 1981, Israeli jets killed two hundred civilians in a single raid on Beirut. By April 1982, we are told, the UN had recorded 2,125 Israeli violations of Lebanese airspace and 625 violations of Lebanese territorial waters.

I recall, and recorded, the bombardment of Beirut in the summer of 1982. It lasted two months, day after day, with, what looked to me of about 250 dead per day with hospitals, schools and apartment buildings destroyed and with people being killed inside of hospitals from the bombardment.

The author tells us that by August, there were 17, 500 civilians killed, 40,000 wounded, 400,000 homeless (10% of Lebanon’s population), and 100,000 without shelter. “Prostrate Lebanon lay devastated and raped without an infrastructure for food or water.”

The Israelis said, “We are here for peace. This is a peace mission.”

The author quotes from veteran Middle East journalist, Robert Fisk, in Pity the Nation, describing Israeli’s use of phosphorus artillery shells, one more Israeli violation of international humanitarian law:

Dr Shammaa’s story was s dreadful one and her voice broke and she told it. ‘I had to take the babies and put them in buckets of water to put out the flames,’ she said. ‘When I took them out half and hour later, they were still burning. Even in the mortuary, they smouldered for hours.’ Next morning, Amal Shammaa took the tiny corpses out of the mortuary for burial. To her horror, they again burst into flames.

The Israeli invasion and occupation of the Arab capital, Beirut, was capped by the massacre at the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps in central west Beirut.

The author says:

The PLO withdrew from Lebanon only after an explicit guarantee from US envoy Phillip Habib and Alexander Haig that the United States of America, with the authority and promise of it President, Ronald Reagan, would ensure the safety of the women and children left defenseless in the refugee camps. Phillip Habib personally signed the document.

Thus the PLO was exiled to Tunisia carrying the written promise of the United States. The fate of those I loved lay in the folds of that Ronald Reagan promise.

She continues:

On September 16, in defiance of the ceasefire, Ariel Sharon’s army circled the refugee camp of Sabra and Shatila, where Fatima and Falasteen [the wife and daughter of Amal’s brother, Yousef] slept defenselessly without Yousef. Israeli soldiers set up checkpoints, barring the exist of the refugees and allowed their Phalange allies into the camp. Israeli soldiers, perched on rooftops, watched through binoculars during the day and lit the night sky with flares to guide the path of the Phalange, who went from shelter to shelter in the refugee camps. Two days later the first western journalist entered the camp and bore witness.

Possibly, as many as 2000 people were either killed in the refugee camps or were taken away in trucks never to be seen again.

She quotes again from Robert Fisk:

They were everywhere, in the road, the laneways, in the back yards and broken rooms, beneath crumpled masonry and across the top of garbage tips. When we had seen a hundred bodies, we stopped counting. Down every alleyway, there were corpses – women, young men, babies and grandparents –lying together in lazy and terrible profusion where they had been knifed or machined-gunned to death. Each corridor through the rubble produced more bodies. The patients at the Palestinian hospital had disappeared after gunmen ordered the doctors to leave. Everywhere, we found signs of hastily dug mass graves.

Even while we were there, amid the evidence of such savagery, we could see the Israelis watching us. From the top of the tower block to the west, we could see them staring at us through field glasses, scanning back and forth across the streets of corpses, the lenses of the binoculars sometimes flashing in the sun as their gaze ranged through the camp. Loren Jenkins [of the Washington Post] immediately realized that the Israeli defense minister would have to bear some of the responsibility for this horror. ‘Sharon!’ he shouted. ‘That fucker Sharon! This is Deir Yassin all over again.’

What we found inside the Palestinian Shatila camp at ten o’clock on the morning of 18 September 1982 did not quite beggar description, although it would have been easier to retell in the cold prose of a medical examination. … these people, hundreds of them, had been shot down unarmed. This was a mass killing, an incident – how easily we used the word ‘incident’ in Lebanon – that was also an atrocity. It went beyond even what the Israelis would have in other circumstances called a terrorist atrocity. It was a war crime.

… these were women lying in houses with their skirts torn up to their waists and their legs wide apart, children with their throats cut, rows of young men shot in the back after being lined up at an execution wall. There were babies – blackened babies because they had been slaughtered more than 24 hours earlier and their small bodies were already in a state of decomposition – tossed into rubbish heaps alongside discarded US army ration tins, Israeli army medical equipment, and empty bottles of whisky.

Down a laneway to our right, no more than 50 yards from the entrance, there lay a pile of corpses. There were more than a dozen of them, young men whose arms and legs had been wrapped around each other in the agony of death. All had been shot at point blank range through the cheek, the bullet tearing away a line of flesh up to the ear and entering the brain. Some had vivid crimson or black scars down the left side of their throats. One had been castrated, his trousers torn open and a settlement of flies throbbing over his torn intestines. The eyes of these young men were open. The youngest was only 12 or 13 years old.

On the other side of the main road, up a track through the debris, we found the bodies of five women and several children. The women were middle-aged and their corpses lay draped over a pile of rubble. One lay on her back, her dress torn open and the head of a little girl emerging from behind her. The girl had short, dark curly hair, her eyes were starring at us and there was a frown on her face. She was dead. Someone had slit open the woman’s stomach, cutting sideways and then upwards, perhaps trying to kill her unborn child. Her eyes were wide open, her dark face frozen in horror.

Ms Abulhawa weaves this historical material of the last paragraph into the story. The woman and child become Amal’s sister-in-law and niece causing her brother, Joseph, to blow himself up along with the 63 persons, including many CIA operatives, at the US Embassy in Beirut. Blowback?

Forgive me, Amal. It is time they taste a small dose of the heaps they have fed us all of our lives.

–Yousef

It is actually unlikely that the suicide bomber who hit the US Embassy was a Palestinian from the occupied territories. Though no one took responsibility for the attack, a new group at the time calling itself Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility for the attack some months later of the Marine barracks near the Beirut airport killing 247 US Marines. Calling themselves, ‘soldiers of God yearning for martyrdom’ the caller said that their goal was an Islamic Republic for Lebanon and the expulsion of the Israelis and their supporters. The Palestinian struggle has been largely secular for most of its history.

In addition to the US broken promises to prevent Israel from invading West Beirut and to protect the refugee camps, which also included Shiite Muslims from southern Lebanon who had taken refuge there after the Israeli invasion, the US had abandoned its neutral stance when the battleship, Virginia, anchored off the coast, shelled Muslim-leftish coalition forces whom it claimed were threatening Lebanese army positions. The destruction of the embassy and its personnel also had the effect of scuttling the signing of a US and Israeli sponsored Lebanese-Israeli peace treaty, likely the main purpose of the bombing.

The State Department, who concluded that the bombing was the work of Hezbollah, was probably right in its conclusion that the bombing sprang from the fermenting soil of the southern Lebanese Shiites but was most likely wrong in the belief that it was Hezbollah which was not even fully formed until 1985.

But ‘blowback’ still. Such a massacre cannot go unanswered, not in the maelstrom of an Israeli invasion which left Lebanon raped with as many as 20,000 killed thanks the American acquiescence to the invasion.

There is the children-instigated Intifada begun in 1988, in which her lifelong friend’s son looses the ability to speak and can no longer look anyone in the eye after arrest and presumably torture under Prime Minister Rabin’s policy of “might, force and beatings.”

The book concludes with Israel’s 2002 massacre at the Jenin refugee camp which was part of the invasion and trashing of West Bank cities during that spring. It does not, however, capture the barbarity and devastation that occurred, and which is comparable to a highly mechanized modern army equipped with Apache and Cobra US made helicopters equipped with air to surface missiles and F16 jet fighters destroying a housing project of largely impoverished people with a handful of defenders armed with only rifles.

A book coming closer to capturing the reality of the massacre is Ramzy Baroud’s book, Searching Jenin. That book consists of personal interviews with about 100 residents of the refugee camp who endured the invasion plus the testimonies of twenty of so international who managed to enter and view there camp some days afterward. Together they describe massive shelling and bulldozing of buildings, men, women, and children being shot by snipers, men being executed with their hands tied behind their backs. One of the internationals whose testimony appears is that of Susan Abulhawa herself.

I found it somewhat improbable that Amal would return to Jenin with her teenage daughter on the eve of Israel’s invasion of West Bank cities and thus put her own life as well as her daughter’s in peril.

I found the style fresh and sometime lyrical and sometimes dreamy as befits an author who also writes poetry.

An interesting and enjoyable book grounded in facts which are a part of the history of the Palestinian people. Perhaps it will reach readers who would not otherwise read through the scholarly historical works.

Ms Abulhawa says in the book Searching Jenin:

Though the heroism of Jenin’s fighters may be perverted by propaganda, history will bow to these lightly armed men who fought until their last breath with an indomitable will and held off a mighty foe for ten days – four days longer than five armies were able to do in the past They are the true sons of the land. Having walked in the wake of what they died trying to prevent, I am changed.